‘More English Fairy Tales’ by Joseph Jacobs

I’ve spoken before on this blog about how much I love folk tales and fairy stories and I think that what the Victorian collectors such as Andrew Lang, Jeremiah Curtin and Joseph Jacobs did is amazing. Every time I visit Cecil Sharp House in Camden I silently give thanks for all the work that Sharp did travelling and recording folk songs and traditions. Yes, they may have ridden rough-shod over issues of ethnicity and shamelessly sanitised the tales for consumption by their Victorian audiences (sex is conspicuous by its absence), but they helped to preserve a tradition of stories which might otherwise have died out completely. How often nowadays do we sit around and listen to people telling stories to one another? I know that outside of folk clubs and festivals its not something that I’ve done since childhood, and while it is a huge shame that this type of social interaction is so rare in modern society, I can only be grateful that the efforts of these men to collect and write down these stories means that they have not passed into obscurity along with the traditional method of their telling.

I’ve spoken before on this blog about how much I love folk tales and fairy stories and I think that what the Victorian collectors such as Andrew Lang, Jeremiah Curtin and Joseph Jacobs did is amazing. Every time I visit Cecil Sharp House in Camden I silently give thanks for all the work that Sharp did travelling and recording folk songs and traditions. Yes, they may have ridden rough-shod over issues of ethnicity and shamelessly sanitised the tales for consumption by their Victorian audiences (sex is conspicuous by its absence), but they helped to preserve a tradition of stories which might otherwise have died out completely. How often nowadays do we sit around and listen to people telling stories to one another? I know that outside of folk clubs and festivals its not something that I’ve done since childhood, and while it is a huge shame that this type of social interaction is so rare in modern society, I can only be grateful that the efforts of these men to collect and write down these stories means that they have not passed into obscurity along with the traditional method of their telling.

I was thrilled, then, to receive a free copy of Joseph Jacobs’ More English Fairy Tales, published recently by Pook Press, from the LibraryThing Early Reviewers programme. This book is a facsimile of the original 1894 edition of the text, complete with gorgeous illustrations from John D. Batten. It comprises an impressive eighty seven fairy tales, many of which are variations on better known versions of the stories, such as the many different versions of Cinderella which appear, and all of which are quite short in length. All in all, it is a lovely collection to read, whether as an adult or a child.

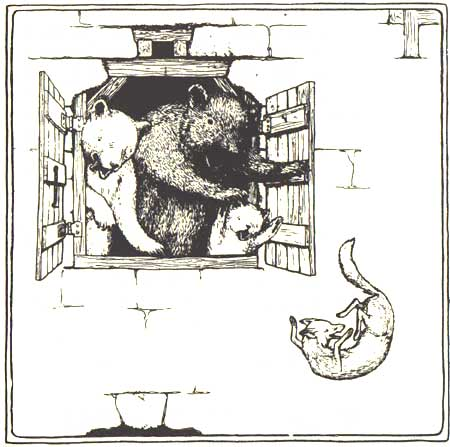

I found the selection of stories really interesting, particularly in instances where they followed a basic outline that was familiar but with some subtle differences. The story that we all know as ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ appears in this collection as the story of Scrapefoot the Fox, who undergoes similar ursine exploits culminating in his being summarily defenestrated by the irate Bears. It makes me curious as to how this character was transformed from a male fox into the little girl Goldilocks from the tale more familiar today (apparently by way of being an old woman and then a young girl called Silver-hair, according to the appendix). Likewise, the well known story of the Pied Piper is altered by moving the setting from Hamelyn to Newtown on the shores of the Solent. I thought this might perhaps have been a change made by Jacobs, appropriating a foreign tale for his book of English stories, as he does warn in his introduction that ‘I do not attribute much anthropological value to tales whose origin is probably foreign‘ (p. x). However, Jacobs’ enlightening ‘Notes and References’ section which closes the book reveals that the story aparently made its way over to England with no help from the author, prompting me to wonder once again how this change took place. I was also delighted to stumble across an early version of what has become one of my favourite folk songs in ‘The Golden Ball’. A girl is to be hung, but cries out to the hangman:

Stop, stop, I think I see my mother coming!

O mother, hast brought my golden ball

And come to set me free?

She then repeats this, protesting that her father has also come to save her. However, each time the response is negative:

I’ve neither brought thy golden ball

Nor come to set thee free,

But I have come to see thee hung

Upon this gallows-tree.

Eventually her sweetheart turns up at the final moment with the promised golden ball and saves her. I first heard this sung while sat in the garden of a pub in Warwick, and fans of the marvellous folk band Bellowhead will recognise this as the song ‘Prickle Eye Bush’, which you can see them performing in all their enthusiastic glory here (seriously, go and watch them). Although the song tells most of the story itself, it’s still really interesting to find out where it comes from and get a bit of background.

For every old favourite, there are also plenty of new tales. I particularly liked the Hobyahs and their exploits, a species of interfering fairy folk who were entirely new to me. The range of different tales and styles is particularly good over the eighty seven stories and I think this would keep the interest of any reader, whether they had a specific interest in the morphology of traditional stories or not. However, for me it is the appendix which makes this book so interesting. Here Jacobs explains where all the tales were gathered, any history behind them and how they differ from other know variations. He strikes the perfect balance between being a storyteller and being an academic folklorist.

For every old favourite, there are also plenty of new tales. I particularly liked the Hobyahs and their exploits, a species of interfering fairy folk who were entirely new to me. The range of different tales and styles is particularly good over the eighty seven stories and I think this would keep the interest of any reader, whether they had a specific interest in the morphology of traditional stories or not. However, for me it is the appendix which makes this book so interesting. Here Jacobs explains where all the tales were gathered, any history behind them and how they differ from other know variations. He strikes the perfect balance between being a storyteller and being an academic folklorist.

It is worth passing comment on the particular edition from Pook Press, as obviously the content of the book hasn’t changed since 1894. More English Fairy Tales has long since passed into the public domain and you can read the whole thing for free, including the illustrations, on Project Gutenburg and it is available in numerous different versions on Amazon, all of which are facsimiles of the same text and so will look exactly the same as this one. With that in mind, it’s a shame that Pook haven’t added anything of their own to the book to induce the book shopper to buy this particular version. It’s a perfectly pleasant little book, but an introduction either from an editor at the company or, even better, from someone who works in the field now or an author who writes modern fairy tales perhaps would have made it stand out a bit more. Pook state that they are ‘working to republish these classic works in affordable, high quality editions, using the original text and artwork so these works can delight another generation of children’ which is an aim that I find admirable, but I think just a few paragraphs explaining why this work is special, how it fits in with their catalogue and a bit of historical context would have been great.

More English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs, illustrated by John D. Batten. Published by Pook Press, 2011, pp. 243. Originally published in 1894.