Review: ‘Human Croquet’ by Kate Atkinson

The Oxfam shop in my old university town used to sell bundles of three books tied up with string for £1.99. I acquired Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson at some point in my final year as part of just such a bundle, along with Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty and A. S. Byatt’s Possession (neither of which I have yet read, shamefully). Both of these were books that I wanted to read, although the time constraints imposed by writing two dissertations put paid to it that year, so I was happy to pick them up, especially as they came with an extra, unfamiliar book thrown into the deal. I knew nothing at all about Kate Atkinson’s book, but nestled as it was between two Booker Prize-winners it was bound to be of a literary bent. I wasn’t really sure what I was in for when I picked it up off my shelf recently, prompted by hearing lots of good things about Atkinson in relation to her Jackson Brodie crime novels, but it certainly looked interesting and, as it transpired, I wasn’t wrong.

The Oxfam shop in my old university town used to sell bundles of three books tied up with string for £1.99. I acquired Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson at some point in my final year as part of just such a bundle, along with Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty and A. S. Byatt’s Possession (neither of which I have yet read, shamefully). Both of these were books that I wanted to read, although the time constraints imposed by writing two dissertations put paid to it that year, so I was happy to pick them up, especially as they came with an extra, unfamiliar book thrown into the deal. I knew nothing at all about Kate Atkinson’s book, but nestled as it was between two Booker Prize-winners it was bound to be of a literary bent. I wasn’t really sure what I was in for when I picked it up off my shelf recently, prompted by hearing lots of good things about Atkinson in relation to her Jackson Brodie crime novels, but it certainly looked interesting and, as it transpired, I wasn’t wrong.

Human Croquet is narrated by Isobel Fairfax and is the story of her family and their neighbours in the village of Lythe. Isobel and Charles’ exotic mother disappeared when they were very young, followed soon after by their father, leaving the children in the care of their steely, old fashioned grandmother and their irascible Aunt Vinny. Even after their father returns several years later no one seems willing to talk about what happened or why. In fact, lots of people in Lythe are hiding things and keeping secrets to themselves, not least Isobel, who keeps finding herself slipping into other periods of time without any explanation.

This is in many ways a very odd book, but it was exactly my kind of odd. My family and I have always played word games and twisted phrases around on themselves, so Isobel’s narration reads rather like I think. The text is peppered with her humorous asides in which she pokes fun at herself:

He runs a hand through his dark curls and brushes them away from his handsome forehead, ‘You’re a good pal, Iz,’ he sighs. I am his friend, his ‘pal’, his ‘chum’ — more like a tin of dog food than a member of the female sex, certainly not the object of his desire.

At other people:

Malcolm Lovat. If I am to have a birthday wish it must be him. He is what I want for birthday and Christmas and best, what I want more than anything in the dark world and wide. Even his name hints at romance and kindness (Lovat, not Malcolm).

And, probably my favourite, when she takes common idiomatic phrases to absurd (yet also supremely logical) lengths:

‘I’m just marking time at Temple’s,’ Charles says, in explanation of his remarkably dull outer life. (Ah, but what does he give it? B-? C+? He should be careful, one day time might mark him. ‘Och, without doubt,’ Mrs Baxter says, ‘that’s the final reckoning.’)

Isabel’s narration is something that I suspect a reader will either love or hate, but for me it was one of the book’s main attractions.

Another aspect of the book that I particularly enjoyed is the way that Atkinson plays around with motifs from fairy tales (Cinderella and Hansel and Gretel spring to mind immediately as examples). She gives the well-known stories subtle nods without ever explicitly copying them, in a way that suggests that all is not quite as it seems. I found it simultaneously reassuringly familiar as I recognised elements of particular stories and unbalancing as what I knew of those stories indicated that things were not going to go as I expected, which is really how the whole novel works: fundamentally a story about family relationships, it is quite happy to have characters turning into dogs or time travelling without any indication that this is somehow unusual.

Atkinson has an approach to writing about different time streams which I have never come across before, but is so wonderfully simple I wonder why it’s not more common. When Isobel is talking about events taking place in the main timeline of the novel, she writes in the present tense; when she narrates scenes from earlier on in her life, they are written in the past tense. The clear definition between what has happened and what is happening is particularly helpful given how confusing and uncertain the reality of the present becomes, and I found the technique to be a good one (and how I wish Sarah Gruen had adopted it in Water for Elephants). Given my dislike of present tense narratives I was surprised by this for the second time this year. It turns out that I quite enjoy the present tense when it is used in a carefully considered manner and employed effectively.

Human Croquet is a bizarre and wonderful book which I suspect readers will either love as unreservedly as I did or find very odd indeed. Either way, it’s definitely worth trying.

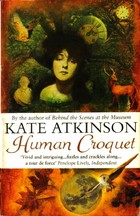

Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson. Published by Black Swan, 1998, pp. 384. Originally published in 1997.