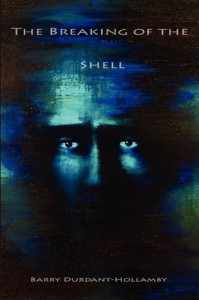

Review: ‘The Breaking of the Shell’ by Barry Durdant-Hollamby

When a horrible tragedy strikes during an innocent childhood game, six year old Alexander Baker’s life is changed forever. It will be many years before the outcome of that day is finally discovered – with consequences that will not only help Alexander to heal his deepest wounds, but also engage him in a process that could lead to global transformation. The Breaking of the Shell is a fascinating story of self-discovery written in a biographical style that explores themes of death, relationship, sexuality, spirituality and material wealth in ways which are sometimes surprising, often humorous and always inspiring. (Goodreads Summary)

When a horrible tragedy strikes during an innocent childhood game, six year old Alexander Baker’s life is changed forever. It will be many years before the outcome of that day is finally discovered – with consequences that will not only help Alexander to heal his deepest wounds, but also engage him in a process that could lead to global transformation. The Breaking of the Shell is a fascinating story of self-discovery written in a biographical style that explores themes of death, relationship, sexuality, spirituality and material wealth in ways which are sometimes surprising, often humorous and always inspiring. (Goodreads Summary)

I feel slightly guilty about not giving this book a good review, as I was sent a free review copy through the Good Reads First Reads programme. I really wanted to like it and be able to say nice things about it, but sadly I can’t. This book should have been given a subtitle; it should have been ‘The Breaking of the Shell: How to Improve your Life and Relationships through Active Listening and Responding to your Emotions’. This book was not a novel, but a poorly disguised self-help book masquerading as a novel to lure poor, unsuspecting people who usually wouldn’t touch such a book with a bargepole (such as myself) into reading it.

Perhaps because the storyline isn’t the main point of this book, it is neither very interesting nor particularly tightly written. At times, such as in the case of the dictaphone, it contradicts itself: Alexander initially listens to the recording in order to hear his father’s declaration of love and yet, when listening to the recording on a later occasion, is surprised to hear the very same at the start of the tape as he hadn’t realised it had been recorded. The character of Helen is introduced without any explanation: she is living with Alexander so I assumed she was his wife, then his girlfriend when that didn’t quite work out, until the first person narrator finally sees fit to tell the reader who this person is (his ex-wife, it transpires). Her characterisation is also inconsistent with what the reader is told: Alexander reports that ‘Helen One’ was dejected and self-doubting, whereas ‘Helen Two’ who emerges after the divorce is confident and bright, but it is impossible to tell the difference between the two Helens when reading through the before and after narratives. The miraculous changes in Alexander are similarly underwhelming and unapparent. It is difficult to see ‘the incident with the garden shed’ (yes, those are the exact words used) as the root of all Alexander’s problems when the author has gone to great lengths to establish that his problems with emotions started before this point and moreover when the ‘incident’ is forgotten and never referred to again for fully half the book. His putative change back into someone who is in touch with his emotions also fails because he isn’t enough of a bastard beforehand for this to be anything spectacular; he’s just a bit misguided and whiney. The lack of any particularly dramatic change in any of the characters means that there is no interesting and satisfying dénouement to this book. Instead, it just sort of peters out long after the time when it should have been put out of its misery.

Apparently the exciting climax of this book is supposedly the earth-shattering discovery that listening to other people and engaging with them makes the world a better place and people happier with each other and themselves (something I’m fairly sure most people could tell you without the aid of this book). At the point when this was discovered any attempt at plot that was anything other than a demonstration of how this system works disappeared entirely. Instead, the reader is treated to descriptions of parents listening to their children, businessmen listening to each other and ultimately the government listening to the people, which is admirable but really not very interesting. Had the narrative up to this point been particularly engaging I might have been able to forgive the new age, touchy feely instructions for self-discovery and the incredible lack of subtlety with which the author set about grinding his own personal axes. As it is, I was left disappointed.

The Breaking of the Shell by Barry Durdant-Hollamby. Published by the art of change, 2010, pp. 334. First edition.

N.B. This is an old review written in 2010 and posted on Goodreads and LibraryThing before I started keeping track of all the books I read here at Old English Rose Reads. I’ve decided to keep copies here so that this remains a complete record of my reading since I started reviewing books for my own pleasure.