‘Lucia in London’ by E. F. Benson

Oh, E. F. Benson, I should never have doubted you! Apologies are also due to the book man in Winchester, whose judgement I was rather doubting after being a little underwhelmed by my first experience of reading a Lucia book. However, it was enjoyable enough for me tocontinue on with the series in spite of my disappointments, and so I picked up Lucia in London, the second book in the series, when in search of something light and fluffy to read and I loved it. This was in fact the first one that I bought, attracted by the lovely cover art, and thankfully I’ve managed to collect all the rest of the books in the same Black Swan editions. Isn’t that picture gorgeous?

Oh, E. F. Benson, I should never have doubted you! Apologies are also due to the book man in Winchester, whose judgement I was rather doubting after being a little underwhelmed by my first experience of reading a Lucia book. However, it was enjoyable enough for me tocontinue on with the series in spite of my disappointments, and so I picked up Lucia in London, the second book in the series, when in search of something light and fluffy to read and I loved it. This was in fact the first one that I bought, attracted by the lovely cover art, and thankfully I’ve managed to collect all the rest of the books in the same Black Swan editions. Isn’t that picture gorgeous?

As the title suggests, in Lucia in London Lucia and Pepino inherit a house in London after his aunt dies. Despite all her protestations of finding London dull and unimaginative compared to Riseholme, it doesn’t take Lucia long to abandon the quiet village and move up to town where she is soon unashamedly engaged in worming her way into London society, assuming familiarity on the slightest of acquaintances and inviting herself to other people’s dinner parties. However, Riseholme does not take kindly to being snubbed and retaliates with a flurry of activity in which Lucia is decidedly not involved. Unused to such independence on behalf of her subjects, Lucia must try to maintain her soveriegnty in Riseholme while battling her way to the top in London.

I think the reason that I enjoyed this book so much more than the first one, despite it being much the same to all intents and purposes, is the fact that it is the second book. A great deal of the fun and enjoyment of the Lucia books comes from knowing the characters and being able to predict exactly how they will behave in any given situation, then laughing at the inevitability of it all, and this sort of familiarity really needs more than one three hundred page book to be developed. Like Olga and her friends in Lucia in London, I have become a Luciaphil, and thoroughly enjoy watching Benson engineer situations in which I know Lucia will behave in a rude, crass manner and equally I know that everyone else will pretend not to notice because a. they’re too polite and b. they’re having just as much fun observing Lucia brazen out awkward social situations as I am. This obvious awareness of the silliness of events but genuine delight in them nonetheless is what makes this book so particularly enjoyable.

I think my favourite incident in Lucia in London involves Lucia deciding to pretend to take a lover, having come to the conclusion that affairs are very fashionable following a celebrated divorce case. However, because she cannot explain that she is going to pretend to be in love to the object of her feigned affections, because this would defeat the object:

But caution was necessary in the first steps, for it would be hard to explain to Stephen what the proposed relationship was, and she could not imagine herself saying ‘We are going to pretend to be lovers, but we aren’t’. It would be quite dreadful if he misunderstood, and unexpectedly imprinted on her lips or even her hand a hot lascivious kiss, but up till now he certainly had not shown the smallest desire to do anything of the sort. She would never be able to see him again if he did that, and the world would probably say that he had dropped her. But she knew she couldn’t explain the proposed position to him and he would have to guess: she could only give hime a lead and must trust to his intelligence, and to the absence in him of any unsuspected amorous proclivites. She would begin gently, anyhow, and have him to dinner every day that she was at home. And really it would be very pleasant for him, for she was entertaining a great deal during this next week or two, and if he only did not yeild to one of those rash and turbulent impulses of the male, all would be well. (p. 170)

Of course, Stephen is about as interested in women as Lucia’s former attendant Georgie, and so hilarity ensues as they each misconstrue the other’s actions.

Although much of the action takes place in London, Riseholme is not neglected. I loved watching them scheming indignantly following Lucia’s mocking of Riseholme and the spread of gossip is a wonder to behold. I felt like I got to know some of the Riseholmites better in this book, and I’m definitely looking forward to spending more time with them in the remaining four Lucia books.

Lucia in London by E. F. Benson. Published by Black Swan, 1986, pp. 266. Originally published in 1927.

Review: ‘The Rivals’ by Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Going to see a play without having read it beforehand always makes me feel a bit like going to see a band play live without knowing many of their songs: slightly awkward and often rather lost. So, when I decided to get tickets for myself and the Old English Thorn to go to see the Haymarket’s recent splendid production of Sheridan’s famous comedy The Rivals, I headed straight over to Amazon immediately after buying the tickets to purchase myself a copy of the play script. Despite not much reading time, I just managed to squeeze it in before heading up to London for a delightful day of culture, in which I went to see the Royal Ballet’s Giselle at the Royal Opera House in the afternoon (note to self: I am too short for standing tickets at the ROH; next time buy a seat) then collected the Thorn and headed off to the Haymarket for The Rivals in the evening.

Going to see a play without having read it beforehand always makes me feel a bit like going to see a band play live without knowing many of their songs: slightly awkward and often rather lost. So, when I decided to get tickets for myself and the Old English Thorn to go to see the Haymarket’s recent splendid production of Sheridan’s famous comedy The Rivals, I headed straight over to Amazon immediately after buying the tickets to purchase myself a copy of the play script. Despite not much reading time, I just managed to squeeze it in before heading up to London for a delightful day of culture, in which I went to see the Royal Ballet’s Giselle at the Royal Opera House in the afternoon (note to self: I am too short for standing tickets at the ROH; next time buy a seat) then collected the Thorn and headed off to the Haymarket for The Rivals in the evening.

The Rivals is a comedy of manners which centres around the tangled love lives of its cast. Captain Jack Absolute has disguised himself as a lowly ensign going by the name of Beverley in order to woo Lydia Languish who, perversely, finds the idea of eloping with a poor man far more romantic than that of marrying a wealthy heir. She is also being courted by Bob Acres, who has no idea that his friend Jack is in fact his hated rival Beverley, and by Sir Lucius O’Trigger, whose letters of love the servant delivers to Mrs Malaprop, Lydia’s guardian, instead of the lady herself. The matter is further complicated when Sir Anthony Absolute arranges with Mrs Malaprop for Jack himself to marry Lydia. The play follows these characters as they cluelessly attempt to work out these increasingly awkward situations.

The Rivals proved to be a most enjoyable, highly entertaining play. My experience of going to see plays is somewhat limited (almost exclusively Shakespeare) so it made a very pleasant change to read and watch a play for which I didn’t need footnotes to understand the jokes and allusions. It was still clever and witty, but it was essentially a situation comedy and so the humour was less word based and a lot less obscure than I’m used to. In fact, I didn’t need to have read the play at all as it was perfectly easy to understand what was going on and to take delight in the confusion on stage without being confused yourself without any prior knowledge of the plot. I always feel a bit guilty dragging the Old English Thorn along to plays as I know I enjoy them far more than he does, on the whole, but he sat next to be laughing uproariously the whole way through.

Of course, the fabulous cast definitely helped. Penelope Keith made a great Mrs Malaprop, pulling off her many amusing lines full of confused words with aplomb and managing to be simultaneously rather haughty and yet still warm and like able. Peter Bowles played alongside her as a stern but jovial Sir Anthony Absolute and the two made a brilliant pair. By far my favourite characters were two of the more minor ones though: Bob Acres made me laugh every time he opened his mouth and Faulkland’s perpetual gloom was just brilliant. The scene in which the two of them discuss Julia, Falkland’s bride to be, was a great piece of comedy and, like the rest of the play, thoroughly enjoyable.

Of course, the fabulous cast definitely helped. Penelope Keith made a great Mrs Malaprop, pulling off her many amusing lines full of confused words with aplomb and managing to be simultaneously rather haughty and yet still warm and like able. Peter Bowles played alongside her as a stern but jovial Sir Anthony Absolute and the two made a brilliant pair. By far my favourite characters were two of the more minor ones though: Bob Acres made me laugh every time he opened his mouth and Faulkland’s perpetual gloom was just brilliant. The scene in which the two of them discuss Julia, Falkland’s bride to be, was a great piece of comedy and, like the rest of the play, thoroughly enjoyable.

Because this play is enjoyable and lighthearted, I don’t think I gained much from the separate experience of reading The Rivals, unlike a Shakespeare play where I feel that when I read the script I notice so many subtle tricks of brilliance that are lost in the general performance when I see the play acted out. I’m sure that I still missed lots of clever things which would be obvious to someone who has studied the play, but for once it was really great to see a play without analysing it and to just enjoy it for what it is: a witty piece of entertainment.

The Rivals by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Published by New Mermaids, 1995, pp. 125. Originally published in 1775.

‘Up the Junction’ by Nell Dunn

I never fail to be impressed by the variety of books published by Virago. Although there have been many relatively recent authors published as Virago Modern Classics, most of the books from this imprint that I’ve read so far have been those written in the early twentieth century. Set in London and first published in 1963, Nell Dunn’s Up the Junction is about as far from the turn of the century icy gentility of The Age of Innocence or the inter-War rural struggles of South Riding as it is possible to get, so I thought it would be an interesting one to pick next.

I never fail to be impressed by the variety of books published by Virago. Although there have been many relatively recent authors published as Virago Modern Classics, most of the books from this imprint that I’ve read so far have been those written in the early twentieth century. Set in London and first published in 1963, Nell Dunn’s Up the Junction is about as far from the turn of the century icy gentility of The Age of Innocence or the inter-War rural struggles of South Riding as it is possible to get, so I thought it would be an interesting one to pick next.

Up the Junction is a slim novella detailing the exploits of a group of young girls working in South London during the 60s. The characters are not particularly well-defined: they tend to blur into each other and often it is impossible to tell who is doing or saying what in any scene. The first person narrator is particularly elusive and difficult to pin down and usually this would annoy me no end. However, this comes across as a deliberate choice and it seems to me that Dunn does not so much tell the story of these people but instead uses her characters to tell the story of a particular time and place in a series of interconnecting vignettes. The frequent bursts of song which appear throughout the novella help to fix this era in the mind of the reader. The characters aren’t really characters at all, but are a means of producing statements and situations which reveal the harsh reality of life in 1960s South London, where times are hard and enjoyment is grasped with both hands and relished. The style reflects this, being bawdy, brash and full of life. Characters express such sentiments as ‘Why should we think ahead? What is there to think ahead to but growing old?’ (p. 78) and ‘what you don’t get caught for you’re entitled to do‘ (p.85) and there is the constant feeling of wringing as much as you possibly can out of a life that is far from perfect.

There is a peculiar mix of free, modern attitudes and traditional values exhibited in this novella. On the one hand, the girls want sex, they want it outside the confines of marriage with whomever they choose and they want to enjoy it, but on the other they accept that they probably won’t enjoy it and would rather suffer an illegal, painful and dangerous abortion than have a baby outside of wedlock, expecting a boy to marry them if they become pregnant. They drink brown ale, they smoke cigarettes and they tell filthy jokes. It’s interesting to see the development here: these girls are not yet quite the Sex and the City girls, but they would like to be, and to make up for having to face harsh realities which aren’t a part of glossy, glamorous twenty-first century New York living they are harder, tougher and earthier.

Up the Junction by Nell Dunn. Published by Virago, 1988, pp. 110. Originially published in 1963.

‘Elfland’ by Freda Warrington

It’s an indication of quite how behind I am with my reviews that I’m only now writing and posting my thoughts on Freda Warrington’s Elfland. This was February’s pick for the Women of Fantasy Book Club hosted by Jawas Read, Too and I finished it back on 14th February. It was a rather appropriate read to finish on Valentine’s Day too as, like the first book club choice, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N. K. Jemisin, it had a much more romantic focus (and for “romance” read “sex”) than I had anticipated.

It’s an indication of quite how behind I am with my reviews that I’m only now writing and posting my thoughts on Freda Warrington’s Elfland. This was February’s pick for the Women of Fantasy Book Club hosted by Jawas Read, Too and I finished it back on 14th February. It was a rather appropriate read to finish on Valentine’s Day too as, like the first book club choice, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N. K. Jemisin, it had a much more romantic focus (and for “romance” read “sex”) than I had anticipated.

Elfland centres around the community of Aetherials, members of a fairy race who have chosen to live in the human world, indistinguishable from regular mortals. Once every seven years, Lawrence Wilder throws open the Gates between the worlds to allow access to the fairy realm, known as the Spiral. However, when the book opens Lawrence refuses to open the Gates and instead seals all entrances to the Spiral in order to keep the Aetherials safe from a threat which he will not name. Some continue with their lives, becoming increasingly human, while others resent Lawrence’s decision and try to find ways to force his hand. Meanwhile the Aetheiral children grow up without ever having visited their magical homeland and both Rosie Fox and her brother Matthew marry humans. But Rosie is continually tempted by a life outside of her mundane, human existence, epitomised in the form of tempting bad boy Sam Wilder. Like the problem of the gates, this cannot be ignored and soon things reach boiling point.

I’m sure there are a great many people out there who love this book, but personally I found it very frustrating. What this book reveals about the Aetherials and the world inside the Spiral as fascinating, but I felt that the fact that the characters were part of a semi-immortal race of fairies was irrelevant for about 70% of the plot which instead focused around normal, mundane things like family relationships and whether the heroine will choose her safe, ordinary husband or the attractive bad boy that she seems unable to resist (hmmmm, I wonder how that will work out. No prizes for guessing). At times it seemed that the only special thing about being Aetherial is that it leads to lots of really great sex. Which is fine, but I wanted to read about how the Aetherials live and the problems of the gate between the two worlds being closed and then cracked open again, not about how much better sex is for them.

Because I picked this book up expecting a fantasy novel, I found the lack of focus on this aspect of the novel to be incredibly irritating. I couldn’t get to like any of the characters, not least because a lot of them were cliche-riddled, but also because I was increasingly annoyed at their interactions distracting from what should have been the main plot concerning the cracking open of the gates. I found myself racing through the relationship stuff in order to get to the main meat of the fantasy plot, only to discover that it never really came. This is a shame, because the little that was shown of the Spiral was fascinating. The Aetherial world and mythology sounds really interesting and I only wish that there had been more of it and that there had been more time given over to developing it.

Elfland is book one of the Aetherial Tales series, of which Warrington has written one more book at present. As her interests and mine don’t really correspond (I like a bit of romance with my fantasy, not the other way around) I doubt I’ll be continuing with the series. It would however be a really great book for someone who typically reads romance novels and would like to try out a new genre.

Elfland by Freda Warrington. Published by Tor, 2010, pp. 610. Originally published in 2009.

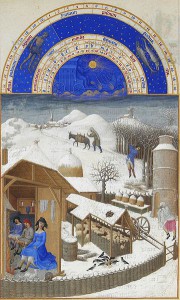

A Time of Abstinence

I’m not a religious person in any way, shape or form, but I enjoy taking part in a lot of the old rites and traditions now associated with the church calendar. Consequently, Tuesday evening heralded an entertaining time in the kitchen as my parents and I attempted to toss pancakes with varying degrees of success. I was a bit too enthusiastic with mine and they tended to flip over twice, landing unhelpfully with the already cooked side facing downwards again. All in all, it was an excellent precursor to the season of Lent, which began on Ash Wednesday.

It’s been a very long time since I gave something up for Lent. Not since the disastrous year when I attempted to give up coffee and had horrible caffeine withdrawal symptoms. This year, however, I have decided to give up buying books. I know, I know, it may come as something of a shock and, I assure you, no one will be more surprised than me if I manage to make it for forty days and forty nights without slipping up and accidentally buying one or two, but it’s a finite challenge with a definite goal and so I should be able to at least give it a good shot.

Wish me luck. I’m going to need it.

‘Marie’ by Madeleine Bourdouxhe

One of my aims for this year is to try to read things which I might not normally pick. French modernist literature features incredibly low on on the list of types of book I usually select (nor for that matter, modernism in any language). Consequently I have no idea how I ended up with Marie by Madeleine Bourdouxhe on my shelves; Simone de Beauvoir was an admirer and quotes the book in her famous work La deuxieme sexe but for once the internet failed me and I was able to find out almost nothing about this book before I read it. There was nothing to do but to plunge straight in and expand my reading horizons.

One of my aims for this year is to try to read things which I might not normally pick. French modernist literature features incredibly low on on the list of types of book I usually select (nor for that matter, modernism in any language). Consequently I have no idea how I ended up with Marie by Madeleine Bourdouxhe on my shelves; Simone de Beauvoir was an admirer and quotes the book in her famous work La deuxieme sexe but for once the internet failed me and I was able to find out almost nothing about this book before I read it. There was nothing to do but to plunge straight in and expand my reading horizons.

It is next to impossible to try to summarise what exactly goes on in this book in the way of plot. All that I can really say is that it follows the relationships of the eponymous Marie, some good and some bad, and watches as they unfold.

The original French title of this book is A la recherche de Marie, an homage to A la recherche du temps perdu, suggesting that it is probably full of very clever allusions to Proust which I completely failed to spot, not having read Proust. In fact, I’m sure anyone who is more familiar with this type of literature would probably find reading Marie a far richer, more involving experience than I did, but as it was I was happy just to drift along, carried by the lovely prose.

This prose is often astute and insightful, and I’m going to have to quote a large chunk of it to give a proper feel for Bordouxhe’s writing:

A few days ago, a young woman in a linen skirt was sitting on a sunny beach. Today, a young woman plunges tanned hands into soapy water, goes down to the cellar to fetch the coal, cleans the floor, peels the vegetables. Marie thinks of other young women she knows and smiles at the astonishment they would feel if they could see her now. What did these other women think of Marie; why does she feel herself to be so different, and why has she never succeeded in really becoming their friend? Perhaps life is simpler if your world is like theirs, confined to choosing wallpaper or sofa covers, to a luxurious home, to the importance of having a maid, to immaculate receptions, to tea parties with friends where a few ideas are exchanged on the latest books. If they have a child, they love it not because it is flesh of their flesh but because it has finally given some point to their existence. They give the impression of being happy or, if they are not, they speak of happiness as an unusable, clearly defined object that need only be discovered and then hung in the apartment like a sprig of mistletoe. (pp. 30-31)

The writing (and indeed the translation) of this book is skillful, alternating as it does between the faintly vague and disconnected atmosphere that I tend to associate with writing of this period and style, and moments of intense, vibrant, passionate immediacy. As Bourdouxhe says:

So it was that whole minutes, hours, years passed by — all full, fine and perfect in their way, but essentially artificial, for if Marie were not in charge of them, these moments would not exist; she alone constructs them, with her heart, her flesh, her personal desires. This was her only faith, and it shone as brightly as the reins she held in her hands. (p. 60)

Marie herself also switches between these two extremes, sometimes quiet and distracted, as though she isn’t really present on the page, and at others vivacious, opinionated and irrepressible. She also seems incredibly modern and forward for a woman of this time, perhaps because the book is quite candid about her sexual encounters. Marie is a truly believable character and the book portrays the meanderings of her mind in such a way that I felt I knew her as much as it is ever possible to know someone (which, as this story suggests, is never as well as you might think). The final chapter, the only one narrated directly by Marie, is simply stunning.

I will definitely be seeking out more of Bourdouxhe’s work after reading Marie. It’s a shame that she seems to be so little known, although perhaps this isn’t true of the French speaking world. I highly recommend her, and at fewer than 200 pages, what have you got to lose?

Marie by Madeleine Bourdouxhe, translated by Faith Evans. Published by Bloomsbury, 1998, pp. 185. Originally published in 1943.

‘The Final Reckoning’ by Robin Jarvis

I’ve recently mentioned how much I enjoy Robin Jarvis’ writing now that I’m reading his Deptford Mice Trilogy as an adult, and The Crystal Prison ended on such a cliffhanger that I had to go on and read the final book in the trilogy, ominously entitled The Final Reckoning, soon afterwards.

I’ve recently mentioned how much I enjoy Robin Jarvis’ writing now that I’m reading his Deptford Mice Trilogy as an adult, and The Crystal Prison ended on such a cliffhanger that I had to go on and read the final book in the trilogy, ominously entitled The Final Reckoning, soon afterwards.

In The Final Reckoning the mice find themselves under threat not only from the army of rats that is massing under London but also from the mysterious eternal winter which has enveloped Deptford. Everything points to Jupiter being back and so the mice, together with the bats and the Starwife, must try to stay alive long enough to defeat him.

You may remember that one of my favourite things about Robin Jarvis’ writing is that he isn’t afraid to be dark even though he is writing for a younger age group, and this book was no exception. Often in children’s fiction, the forces of evil (whatever form they may take) are distant, incompetent or impotent or a combination of all three. Evil is usually active in a far off land to which the protagonist must journey to fight it, its plans fail fairly easily before they can be put into practice, and if a character is important and liked then Evil will frequently content itself with capturing rather than killing them. All in all, Evil often isn’t terribly threatening. However, the forces of evil in Jarvis’ books are immediate, powerful, bloodthirsty and indiscriminate in who they attack. Just because a character has a name and has been well developed does not mean that they are safe. I love that I can read a book for younger readers entitled The Final Reckoning with a final chapter also called ‘The Final Reckoning’ and do so with apprehension because I don’t know which, if any, of the characters will make it through to the end alive. There is real tension and anxiety in these books which I’ve not often found in children’s fantasy. Of course, this might be far more common in children’s literature now, I don’t know, but I still think Jarvis should be applauded for what he has done, particularly considering The Deptford Mice Trilogy is more than twenty years old.

The Final Reckoning by Robin Jarvis. Published by Macdonald, 1997, pp. 305. Originally published in 1990.

February Review

Now, I know that the end of January slipped by without a review post, but I decided that if I don’t start writing them now I never will. I like the idea of having a proper summary of what I’ve read each month, particularly for months like this when I’m so very far behind. It’ll also help me to keep track of incoming and outgoing books now that I’ve removed the TBR tab from my blog. It was proving too difficult to maintain, so I’ve decided to stick with keeping my TBR pile on LibraryThing where it’s much easier to track. I will still be doing the TBR lucky dip each month from there.

Now, I know that the end of January slipped by without a review post, but I decided that if I don’t start writing them now I never will. I like the idea of having a proper summary of what I’ve read each month, particularly for months like this when I’m so very far behind. It’ll also help me to keep track of incoming and outgoing books now that I’ve removed the TBR tab from my blog. It was proving too difficult to maintain, so I’ve decided to stick with keeping my TBR pile on LibraryThing where it’s much easier to track. I will still be doing the TBR lucky dip each month from there.

With a few notable exceptions, February has been a distinctly unremarkable reading month. I’ve read 17 books this month, a lot of which have been enjoyable at the time but largely forgettable. There’s nothing wrong with reading books like this, but I’m hopeful that March will contain more books which are better than ‘quite good’. February’s books are:

- Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Cape Town by Paul Theroux

- The Crystal Prison by Robin Jarvis

- Wolfwatching by Ted Hughes

- A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr

- The Final Reckoning by Robin Jarvis

- Marie by Madeleine Bourdouxhe

- Elfland by Freda Warrington

- Up the Junction by Nell Dunn

- The Rivals by Sheridan

- How Obelix Fell into the Magic Potion when He Was a Little Boy by Goscinny and Uderzo

- Lucia in London by E. F. Benson

- The Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith

- Tam Lin by Patricia Dean

- The Victorian Chaise-Longue by Marghanita Laski

- City of Glass by Paul Auster

- Miss Buncle’s Book by D. E. Stevenson

- Through England in a Side-Saddle by Miss Celia Fiennes

The stand-outs by far were A Month in the Country and The Victorian Chaise-Longue both of which I loved, although they’re very different books: one is cosy and nostalgic and the other is claustrophobic and intense. Although I didn’t manage to participate in Persephone Reading Weekend, this publisher was well represented in February’s reading, as Miss Buncle’s Book was also very enjoyable and I look forward to reading more by D. E. Stevenson in the future. I read 12 new authors this month, everyone but Robin Jarvis, Ted Hughes, E. F. Benson and the fantastic duo of Goscinny and Uderzo being people that I had never read before, so it’s good I’m trying new things even if they’ve proved to be a little underwhelming at times.

Now onto the scary bit: the incoming books.

Now onto the scary bit: the incoming books.

From Amazon: I buy books from Amazon quite rarely; as a rule I only tend to buy a book from here when I want/need (and you know how easy it is to confuse these two when it comes to books) to read it immediately, and then it’s usually from the Marketplace. The Rivals by Sheridan was a book I needed in a hurry as I booked last minute tickets to see the fabulous production at the Haymarket and wanted to read the script first. I ordered Prospero Lost by L. Jagi Lamplighter as the March read for the Women of Fantasy Book Club. Andrew Lang: A Critical Biography by Roger Lancelyn Green isn’t one that I want to read right now, but I know I’ll want to read this book as I’m currently working my way through the gorgeous reissues of Lang’s Fairy Books from the Folio Society and the man is so interesting. It’s out of print and Amazon only had a few copies so rather than wishlisting it, I went ahead and ordered it already.

From Ebay: This year I’ve decided to revisit the Asterix books as I enjoy them so much, reading them in series order for the first time. I already own most of them, but I picked up How Obelix Fell into the Magic Potion when He Was a Little Boy, the prequel to the series, and Asterix and the Golden Sickle to go towards completing my collection.

From BookMooch: Despite having over 700 books on my wishlist, it went very quiet towards the beginning of the year, but it’s picked up again this month (unfortunately for my TBR pile). Country of the Pointed Firs and Other Stories by S. O. Jewett was one I only listed this month after seeing it recommended on LibraryThing, but a copy was available straight away. Geek Love by Katherine Dunn turned up courtesy of a lovely newbie BookMoocher. I finally managed to get hold of a copy of Riddle of the Seven Realms by Lyndon Hardy, the third part of a trilogy that I’vehad on my shelves for ages. Sex with Kings by Eleanor Herman is added to my pile of non-fiction books for the year. I obtained a copy of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat entirely because I want to read Connie Willis’ books and get the inside jokes. The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ by Philip Pullman joins my small collection of books in the marvellous Canongate Myths series. I periodically search for Virago Modern Classics just to see if any have been listed and this month I was able to mooch a copy of Precious Bane by Mary Webb.

From charity shops: I’ve done incredibly well from charity shops this month, partly because I have to walk past the Bloomsbury Oxfam bookshop once a week and partly because I had to go into a nearby town at the weekend to do boring bank stuff and it was only fair to reward myself with a nuff in the charity shops. I struck gold in the Bloomsbury Oxfam though, as I not only did I obtain my £2.99 copy of The Victorian Chaise-Longue by Marghanita Laski (which I read instantly) there, I managed to pick up two particularly special copies of books for £3 each: a copy of Penguin Lost by Andrey Kurkov signed and with a penguin drawing by the author, and a copy of A Game of Hide and Seek by Elizabeth Taylor with a dedication inside from Nicola Beauman to Ismael Merchant! From my own town I obtained The Woven Path by Robin Jarvis, Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote, Ivy by Julie Hearn and The Lagoon by Janet Frame from the shop where books are 2 for £1. Also for the princely sum of 50p each I acquired The Science of Harry Potter: How Magic Really Works by Roger Highfield and a 1923 hardback of a book called The Winding Stair by A. E.W. Mason (I have no idea what this one is about but I look forward to finding out). In the slightly more expensive shops, I paid £1 each for a lovely old hardback edition of Village School by Miss Read, Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, W. B. Yeats: The Love Poems, a pristine copy of Tove Jansson’s A Winter Book and the Persephone edition of Little Boy Lost by Marghanita Laski which I’m especially looking forward to after my first experience with this author. See, I may acquire a lot of books but I’m far from profligate.

From The Book People: This company proves fatal to the sternest of resolves not to buy too many books (and my resolve was always a long way from being stern) because their books are just so cheap! I acquired The Vintage Maugham Collection of ten beautiful books from an author I’ve been meaning to read for ages. I also bought the lovely Penguin English Journeys box set, containing twenty slim volumes all of which I’m dying to read (and one of which I succumbed to right away). Finally, I bought the complete eight book set of the Penguin Pocket Sherlock Holmes. I’ve already read the first two and I owned another three of them but it was still cheaper to buy the entire set of eight books than to buy the remaining volumes that I needed to complete the set. This company is going to be dangerous, I can tell.

From The Book People: This company proves fatal to the sternest of resolves not to buy too many books (and my resolve was always a long way from being stern) because their books are just so cheap! I acquired The Vintage Maugham Collection of ten beautiful books from an author I’ve been meaning to read for ages. I also bought the lovely Penguin English Journeys box set, containing twenty slim volumes all of which I’m dying to read (and one of which I succumbed to right away). Finally, I bought the complete eight book set of the Penguin Pocket Sherlock Holmes. I’ve already read the first two and I owned another three of them but it was still cheaper to buy the entire set of eight books than to buy the remaining volumes that I needed to complete the set. This company is going to be dangerous, I can tell.

Finally, in non-bookish but most exciting news, February also saw the purchase of a wedding dress! That doesn’t make me look and feel like either a tragic heroine from a Victorian novel or an extra from My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding! I can’t post any pictures or give any hints as to what it looks like, but suffice to say that it is beautiful and I love it and I cannot wait to marry the Old English Thorn while wearing it. It’s only six months to go now and I am so excited!

‘A Month in the Country’ by J. L. Carr

Although I’m usually pretty good about writing reviews for books shortly after I finish them, I’ve fallen rather behind recently and find myself faced with a stack of ten books which have been read but not yet reviewed. At the top of that pile is J. L. Carr’s short novella A Month in the Country and it is reminding me of exactly why I try to write reviews while the books are still fresh in my mind as I’m finding it very difficult to put into words what was so marvellous about this book. A Month in the Country is quietly brilliant but it is one of those books that is very difficult to catch in the act of being so.

Although I’m usually pretty good about writing reviews for books shortly after I finish them, I’ve fallen rather behind recently and find myself faced with a stack of ten books which have been read but not yet reviewed. At the top of that pile is J. L. Carr’s short novella A Month in the Country and it is reminding me of exactly why I try to write reviews while the books are still fresh in my mind as I’m finding it very difficult to put into words what was so marvellous about this book. A Month in the Country is quietly brilliant but it is one of those books that is very difficult to catch in the act of being so.

The story is told as the memoir of Tom Birkin, a scarred and shell shocked survivor of the Great War, of the summer when he spends a month staying in the bell tower of the church in Oxgodby while he works on uncovering a medieval wall painting there. It is a chronicle of the work he does and the characters he meets as he gradually becomes absorbed into the life of the village.

This is the sort of work which epitomises the phrase ‘small but perfectly formed’: my copy has a mere 111 pages but every single one of those is significant and carefully crafted. On the one hand it’s a simple story of slow village life, but on the other it’s a narrative of rediscovery and restoration, both of the medieval painting in the church and of Tom Birkin himself, and so the work in Oxgodby church forms an ideal focus for the book. It encapsulates the themes of the novella, which is tinged with a bittersweet nostalgia which makes for compelling reading.

Just as Tom finds himself inexplicably taking part in activities such as preaching in a sermon in a neighbouring village without really knowing how or why he agrees to it, I found myself being inexorably drawn into Oxgodby’s world of little things; every now and then I would step back from myself and realise that I had been utterly absorbed in a discussion of the comparative merits of different types of furnaces and was genuinely interested in this. Stoves are, I hasten to add, not normally something I find particularly fascinating, so the fact that I found them, along with every other mundane detail in this book, so very engaging is testament to J. L. Carr’s skill as a writer. In reading this book, I felt like I spent a glorious month in the country along with Tom Birkin, and it is an experience not to be missed.

A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr. Published by Penguin in association with Harvester Press, 1983, pp. 111. Originally published in 1980.

‘Wolfwatching’ by Ted Hughes

If you were to ask me to name my favourite poet, I would have a very hard time naming just one, as I read different people for different things. I read Robert Browning for his amazing dramatic monologues; John Donne for his fiery passion, whether holy or secular; W. B. Yeats for his mysticism and occultism; Shakespeare for wit and brilliance; Hillaire Belloc, Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll for their humour; and there are a host of others I can turn to in any given mood. Ted Hughes, I read primarily for his nature poetry which illuminates creatures and landscapes that I see all the time with a clarity and accuracy which make me see them in a new way.

If you were to ask me to name my favourite poet, I would have a very hard time naming just one, as I read different people for different things. I read Robert Browning for his amazing dramatic monologues; John Donne for his fiery passion, whether holy or secular; W. B. Yeats for his mysticism and occultism; Shakespeare for wit and brilliance; Hillaire Belloc, Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll for their humour; and there are a host of others I can turn to in any given mood. Ted Hughes, I read primarily for his nature poetry which illuminates creatures and landscapes that I see all the time with a clarity and accuracy which make me see them in a new way.

Wolfwatching is a collection of poems which divides fairly evenly into the nature poems that I love so much and poems about Hughes’ father and their relationship. I personally prefer the former type because of the shocks of recognition that they provide; the poems which aren’t centred around the natural world are more opaque and harder to pin down, but they feel profound even if I don’t understand them as well. It is a slim volume of only 55 pages, but it is powerfully written and full of beautiful phrases.

As I find it almost impossible to review poetry, I thought I would share some of my favourite passages instead. The first example is drawn from the first poem in the book, ‘A Sparrow Hawk’:

Those eyes in their helmet

Still wired direct

To the nuclear core – they alone

Laser the lark-shaped hole

In the lark’s song.

I love how it both physically describes the bird and conveys the speed, efficiency and deadliness of the hawk’s attack.

Next is an offering from ‘Manchester Skytrain’, perfectly describing a highly-strung racehorse:

Every known musical instrument

The whole ensemble, packed

Into a top-heavy, twangling half ton

On the stilts of an insect.

And finally, the famous ending of one of the more esoteric poems in the collection, ‘Two Astrological Conundrums II: Tell’:

With all my might – I hesitated.

Wolfwatching by Ted Hughes. Published by Faber and Faber, 1989, pp. 55. First edition.