‘The Poisonwood Bible’ by Barbara Kingsolver

I’ll be honest: I don’t know very much about Africa other than that it is quite hot. Nor, for that matter, have I read many books set there other than those thrust upon me at university. I don’t actively dislike Africa as a setting for literature, I just tend to gravitate more towards Victorian and neo-Victorian novels, historical medieval fiction and turn of the century British women’s writing which tend to be located in, well, England. Most recently, I read Chinua Achebe’s much lauded postcolonial novel Things Fall Apart and didn’t really get on with the story, although I enjoyed the cultural element of the book. Consequently, it was with some trepidation that I approached The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver, but I needn’t have worried. The writing was exquisitely well balanced, the story was absorbing and the Congo was portrayed as though it were another character rather than merely a place. I loved it and it was the perfect book with which to begin 2011 (yes, only two weeks late and I’m finally reviewing 2011 books.

I’ll be honest: I don’t know very much about Africa other than that it is quite hot. Nor, for that matter, have I read many books set there other than those thrust upon me at university. I don’t actively dislike Africa as a setting for literature, I just tend to gravitate more towards Victorian and neo-Victorian novels, historical medieval fiction and turn of the century British women’s writing which tend to be located in, well, England. Most recently, I read Chinua Achebe’s much lauded postcolonial novel Things Fall Apart and didn’t really get on with the story, although I enjoyed the cultural element of the book. Consequently, it was with some trepidation that I approached The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver, but I needn’t have worried. The writing was exquisitely well balanced, the story was absorbing and the Congo was portrayed as though it were another character rather than merely a place. I loved it and it was the perfect book with which to begin 2011 (yes, only two weeks late and I’m finally reviewing 2011 books.

The Poisonwood Bible tells the story of the Price family who travel from Georgia to act as missionaries in the Congo in 1959. The story is told through the eyes of the mother, Orleanna, and her four daughters, Rachel, Leah, Adah and Ruth May and the reader experiences everything through them, from day to day trials and tribulations to significant tragedies, from personal hardships to national political upheaval which swept the Congo in the 1960s following its independence. The story does not end with the conclusion of their time in Africa, but extends beyond this to show the impact that the events that took place there have had on all the family members. Neither religion nor politics are favourite themes of mine, but the novel is about so much more than this; they provide a framework for what is really an exploration of humanity.

Writers who can successfully assume several voices in one novel and actually make them distinct enough that I can tell who is speaking without having to check the chapter headings impress me immensely, and Barbara Kingsolver has this down to a fine art. All of the Price women are determinedly individual and, through their differing perspectives, they each reveal different aspects of life in the Congo. Orleanna’s narratives are always written retrospectively and are filled with a barely restrained hysteria from the very beginning, the reasons for which only become clear towards the end of the book. Rachel is the eldest and the most resistant to life in the Congo, and her sections are a heartbreaking combination of trying to act and sound grown up while desperately needing to be babied and looked after in this strange land. Leah, the stronger of the twins, is the most vocal of all the women and adapts best to Congolese ways. Through her, although the reader still sees the village of Kilanga and its inhabitants from the perspective of a white outsider, it is the perspective of a white outsider who understands and does her best to be assimilated and accepted among the Africans. Adah is Leah’s physically weaker twin, partially crippled from birth and largely silent. Her sections of the narrative display a fey intelligence and shrewdness and her observations into the people around her are keen. Ruth May is the baby of the family, and her parts of the story are filled with a bittersweet innocence, as she observes and reports the situations around her without comprehension of their true meanings or implications. With these five remarkable women, Kingsolver weaves a tapestry of life in the Congo at this difficult time which had me completely emotionally engaged from beginning to end.

In addition to drawing me in on the levels of character and plot, The Poisonwood Bible is highly technically written as language, both in practice and as a concept, is very important and every single word feels as though it has been carefully chosen for maximum impact. Rachel, for example, frequently gets words confused in her attempts to sound older than she is and so will often say things that are either not what she means or are just nonsense. I’m also reasonably sure that she never uses Congolese words or phrases, indicative of her resistance to the culture and her desire to remain separate, whereas the other women all gradually absorb these into their vocabulary. Adah in particular thrives on these new words and their possible uses as she turns language inside out and upside down in order to extract every possible nuance of meaning from them. Her use of palindromes and the way that Kingsolver deploys them throughout the book is something that I found particularly interesting. It is also telling that silent girl is the one who understands language the best, as it draws attention to all the things in this book that go unsaid. I never thought I’d use these terms outside of university, but Kingsolver makes excellent use of the gap between signifier and signified.

In short, I found this book brilliant on every level, and I cannot recommend it highly enough.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver. Published by Faber andFaber, 2000, pp. 616. Originally published in 1998.

‘The Last Battle’ by C. S. Lewis

One of my aims for 2010 was to read all of C. S. Lewis Narnia books, so it seems appropriate that my final book for 2010 was The Last Battle (I apologise for being so behind with reviews; Christmas and New Year are not terribly convenient times for spending time on the computer). Although I was already vaguely aware of what happened in the books and have dim recollections of the old BBC series, I’ve really enjoyed discovering the books properly and I’m sad to see it end.

In The Last Battle, all is not well in Narnia. King Rilian, whom we met in The Silver Chair, is greeted with the disturbing news that the dryads’ trees are being cut down, talking Animals are being used as beasts of burden by the brutal Calormenes and all this appears to be happening at Aslan’s orders. Meanwhile, Jill and Eustace, travelling back to school on the train, suddenly find themselves jolted back into Narnia where they join with King Rilian and the loyal folk of Narnia in fighting for survival against the Calormenes.

Unfortunately, I think that this book was the point at which C. S. Lewis’ interests and my own completely diverged. Never before have I wished so much that I had read these books when I was young enough not to notice that I was being beaten around the head with the baseball bat of allegory. What started out as subtle nuances and echoes of Christianity which worked well within the framework of the story became the story. As I read the Narnia books for their stories, I was disappointed by this turn towards outright preaching, particularly as the ending which illustrated C. S. Lewis’ idea of Christianity wasn’t what I would have envisaged as a satisfactory ending on a narrative level. I understand that this was his motive for writing the books and that my disappointment is because of my different priorities, but I do wish that he’d been able to (or more likely chosen to, I have no doubts about his writing capabilities) blend the two aspects of the book, fantasy adventure story and religious message, as seamlessly as he did in the previous books.

However, although I found the message a bit heavy handed, there was still much about this book that I loved. I thought that the descriptions of the battle itself were very well executed: they convey both the tension and nervous excitement of waiting for things to happen and then the frenzy of confused activity as an attack takes place. Considering this action takes up about half of the book, I was impressed at how Lewis sustained this level of intensity and it makes the book an easy one to whizz through. I also thought that the introduction of Tash, the cruel god of the Calormenes, was an interesting touch and the image of him passing through Narnia is a chilling one.

It seems that in every book there’s at least one wonderful new character — Mr Tumnus and the Beavers in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Bree in The Horse and his Boy, Trumpkin in Prince Caspian, Reepicheep in The Voyage of the Dawntreader and Puddleglum in The Silver Chair – and in The Last Battle for me it was Shift the Ape and Puzzle the Donkey about whom I most enjoyed reading. The dynamic between the two, Puzzle innocent and eager to please, Shift controlling and cunning, is established from the very beginning and it manages to be amusing even though it is quite dark and swiftly becomes one of the obvious references to Revelation. This double act provides a light introduction to a book which develops into something quite serious and I thought it created a good contrast to the book’s later seriousness.

All in all, I’m sad to leave Narnia but, as a non-Christian, I wish I hadn’t left it so late to read and so had been able to enjoy the books without the religious message intruding on the stories. Most of the time this wasn’t a problem, but The Last Battle was just a bit too overt for me to really enjoy it.

The Last Battle by C. S. Lewis. Illustrated by Paula Baynes. Published by Diamond, 1996, pp. 172. Originally published 1956.

Slightly Foxed 11: A Private, Circumspect People

As the vast majority of my reading takes place on public transport of one form or another, I am mostly unperturbed by the prospect of tackling weighty books while surrounded by the inevitable distractions that ensue when there are Other People around. Nonetheless, when the mode of transportation in question is an aeroplane, it’s nice to have a magazine to read as it provides small, easily digested chunks of reading, perfectly sized for reading in between tannoy announcements apologising that the aforementioned aeroplane is going to be late (curse you, Scottish fog!). Thus I was pleased to have Slightly Foxed 11: A Quiet Circumspect People in my bag when the Old English Thorn and I were treated to an unexpected leisurely wait at the airport, followed by an even more unexpected scenic coach tour of the motorway between Glasgow and Edinburgh when our plane was unable to land.

As the vast majority of my reading takes place on public transport of one form or another, I am mostly unperturbed by the prospect of tackling weighty books while surrounded by the inevitable distractions that ensue when there are Other People around. Nonetheless, when the mode of transportation in question is an aeroplane, it’s nice to have a magazine to read as it provides small, easily digested chunks of reading, perfectly sized for reading in between tannoy announcements apologising that the aforementioned aeroplane is going to be late (curse you, Scottish fog!). Thus I was pleased to have Slightly Foxed 11: A Quiet Circumspect People in my bag when the Old English Thorn and I were treated to an unexpected leisurely wait at the airport, followed by an even more unexpected scenic coach tour of the motorway between Glasgow and Edinburgh when our plane was unable to land.

Slightly Foxed is a wonderful quarterly literary magazine, and really isn’t something that you should read if, like me, youre trying to reduce your pile of books to read. The essays in Slightly Foxed look at books old and new with an appreciative, affectionate eye rather than a critical one; reading through it is a bit like chatting to a selection of people about what their favourite books, all of them keen to persuade you to read and love them too. And, you know me and books, I need very little persuading. Because there’s no bias towards newly published books, many of these essays are about books and authors I’ve never heard of before, which makes a refreshing change.

As this would be almost impossible to review, I’m instead going to share some of the things I want to read thanks to this issue of Slightly Foxed, so I can add to your wishlists as well as my own.

Akenfield: Portrait of an English Village by Ronald Blythe – Maggie Ferguson talks about discovering this book while working at the Royal Society of Literature and it sounds just my sort of thing, presenting a simple, heartfelt view of a vanishing rural life that is at once nostalgic and realistic.

Leo the African by Amin Maalouf – I don’t think I’ve ever read anything by a Lebanese author, but the snippets of this novel provided by Justin Marozzi are so beautiful that I definitely want to investigate it for myself.

The Modesty Blaise books by Peter O’Donnell – I am a big fan of ridiculous books as long as they don’t take themselves seriously, and Amanda Theunissen makes this thriller series with its feisty heroine sound great fun.

Anything by Anna Kavan – I’m not sure that Anna Kavan’s fiction iis going to be entirely for me, concerned as it is with drugs and madness, but Virginia Ironside makes the life of this woman sound so interesting in this essay that I’m going to give it a try anyway.

The Leopard by Guiseppe di Lampedusa – John de Falbe is so enthusiastic about this book and its author, whose life and family seem completely bizarre, that I’m intrigued.

The Papers of A. J. Wentworth BA by H. F. Ellis – Jeremy Lewis recommends these fictional memoirs of a beleaguered school master. H. F. Ellis was one of the contributers of Punch, which is yet another reason to read this book and see if it is as entertaining as it sounds.

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman – This book, recommended by Julia Keay, is an account of the clash of cultures when a Hmong family who speak very little English emigrate to America, bringing with them their epileptic daughter. It sounds like a fascinating idea, so onto the wishlist goes this book.

I think I’ll leave myself a good break before I open another copy of Slightly Foxed as I can’t keep acquiring book recommendations at quite the rate it provides them. Book lovers beware!

TBR Lucky Dip: January

As I explained in my post about reading plans for the new year, each month I’m going to be using a random number generator to select a book from my TBR pile for me to read, to help me read more widely from my shelves.

This month, the deities of www.random.org have ordained that I should read book number 222. According to my TBR list this means that I am reading…

Lady’s Maid by Margaret Forster.

When she arrived in London in 1844 — young and tremulous but full of sturdy Northern good sense and awakening sophistication — Lily Wilson became more than a lady’s maid to the fragile, housebound Elizabeth Barrett. Her mistress’s gaiety and sharp intelligence, the power of her poetry, and her deep emotional need drew “Wilson” into a strange intimacy that would last sixteen years.

It was Wilson who smuggled Miss Barrett out of the gloomy Wimpole Street house, witnessed her secret wedding to Robert Browning in an empty church, and fled with them to threadbare lodgings and the heat, light and colours of Italy. As housekeeper, nursemaid, companion and confidante, she was with Elizabeth in every crisis — birth, bereavement, travel, literary triumph. As her devotion turned almost to obsession, Wilson forgot her own fleeting loneliness and the barrier between mistress and maid turned to gossamer. And when Wilson’s own affairs took a dramatic turn, she came to expect the loyalty from Elizabeth that she herself had always given.

Artfully weaving fact and fiction, Margaret Forster has uncannily captured the tone and passion of a classic Victorian novel — the intricate nuances of relationship, the social limitations of servitude and womanhood, and the poignant bloom of affections injured and reborn.

This book came to me from BookMooch not too long ago, and it sounds as though I should really enjoy it. Good choice, book selection gods! Has anyone else read this yet?

‘The Silver Chair’ by C. S. Lewis

The Narnia series has a great many things to recommend it to readers, but their chief appeal for me at this particular moment in time is how small and compact they are, thus making them the perfect books to read on the tube. I’ll soon be looking for some new light reading (both literally and figuratively) to take the place of C. S. Lewis’ books though, as The Silver Chair brings me to the penultimate installment in the Narnia series and it has the distinct feel of a series winding down to its conclusion.

In this book, another new human is introduced to Narnia in the form of Jill Pole. When trying to avoid the school bullies, Jill and Eustace implore Aslan to help them and soon find themselves in his country. There he tasks them with finding King Caspian’s missing son and restoring him and so, assisted by Puddleglum the marshwiggle, they set out to find Prince Rilian .

Although, like The Voyage of the Dawntreader, this is essentially a quest book it felt much more continuous and natural, where I found the previous book too episodic and patchy. It has a much more realistic scope and so events feel like a logical progression dependent on things that have happened before rather than a series of unconnected occurrences happening one after another. As a result of this, I found The Silver Chair much more enjoyable to read than the previous book. Many of the parts of the story were familiar rather than original, such as the children’s adventures in the city of giants and the silver chair itself, but Lewis tells them in such a charming way that I didn’t mind. Other parts, however, are wonderfully new: I thought that Underland and Bism were excellent creations.

What made this book so enjoyable to read was the presence of Puddleglum the marshwiggle. His irrepressible gloom and pessimism provides an unexpected comic touch which had me smiling throughout. The Silver Chair shows a marked movement towards the end of days state which will emerge fully in The Last Battle with the book taking a turn towards being darker and more serious (I think this book is the first time when a good character dies and is not brought back to life) this light relief is a welcome change of tone. I’ll be sad when I finish my exploration of Narnia, but I look forward to seeing how exactly Lewis manages to do it.

The Silver Chair by C. S. Lewis. Illustrated by Paula Baynes. Published by Diamond, 1996, pp. 1991. Originally published 1953.

‘Baudolino’ by Umberto Eco

Baudolino first came into my possession when I was helping a friend sort through some of his books at university when he moved from a large room into a much smaller one. When I unearthed this book, he expressed surprise that I hadn’t already read it and then insisted that I rehome it as naturally, being a medievalist, I would love it. Never one to turn down a free book, I took it off his hands and then, being not only a medievalist but a medievalist in the middle of writing her MA dissertation, it promptly became buried under a stack of less medieval brain candy for essential light relief. I had completely forgotten about it until a colleague lent me the same book, also insisting that I would love it. As this chap delights in giving people books to read, all of which so far have been universally loathed by the reluctant recipients, this was hardly an encouragement. Nonetheless, this meant that I now had two copies of the book staring accusingly at me from my shelves and the cumulative guilt finally proved too much, so I gave in and read the book.

Baudolino is a difficult book to summarise, because the more you read, the more you realise that the plot is merely incidental and the book is really about something else entirely. In fact, if you were to read this book for the plot you would be very confused very quickly. The story is a first person account by the eponymous Baudolino of his life, as told to Niketas whom he rescues from the sack of Constantinople. It chronicles his adventures from 1155 when he was adopted in all but name by Emperor Frederick I up to the fourth Crusade which is the present day of the novel. In between he falls in love, studies in Paris, negotiates peace agreements, saves cities, and searches for the legendary kingdom of Prester John. However, what the book is really about (I think; it’s a bit difficult to tell with Eco) is what is true and what is not and how easily one can become the other.

Baudolino himself is established as an unreliable narrator from the very beginning of the novel. The book begins with him quite literally erasing history and writing his own story over the top of it when he scrapes clean some parchment containing historical records for his own personal use. He goes on to fabricate love letters which he considers more true than if they had really been sent to him by the object of his affection (who is of course, like Dante’s lady love, called Beatrice). He creates religious relics from household junk. He invents a letter from Prester John to Frederick which sends Baudolino and his friends off on an impossible journey to find the kingdom that they themselves have created, bearing a cup which they style as the grail. These stories not only take in others, but they even fool their creators as Baudolino and his friends seem to come to believe in their own fictions, so the reader stands no chance of working out what is true and what is not. Why should his first person narrative to Niketas be any more factual than any of this? And does it matter if it is true or a lie? Eco seems to be asking whether there is a difference at all, and with the amount of blurring that goes on in this book it is impossible to say.

By far my favourite part of this book was Baudolino’s own manuscript which begins the novel, written in a strange, hybrid language which is a mixture of Latin and how he thinks his native tongue ought to sound if it were to be written (and kudos to William Weaver for finding a way to translate this so that it works in English). This is so very medieval in spirit, right down to his having scraped the parchment clean of another text and written his own story over the top of it (although parts of the original manuscript still show through at points), that I couldn’t help but enjoy it. This was the first in a long series of in jokes for medievalists which I found enormously entertaining but I’m not sure would have been appreciated as much by someone without this background; even with my education in this area, at times I felt as though I needed to read armed with an encyclopedia of the medieval world to pick up on everything and I’m sure I missed a great deal. Eco may be writing fiction, but this book is very scholarly, employing and satirising a whole host of medieval tropes and conventions, from Provencal troubadour verse to debate on religious heresies, from courtly love to fantastic travelogues and from philosophy to the inexplicable lists, ubiquitous in medieval literature. Baudolino is a gold mine of satire on the middle ages, but it is hard work to read.

Baudolino by Umberto Eco. Translated by William Weaver. Published by Vintage, 2003, pp. 522. Originally published in 2000.

‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ by C. S. Lewis

Back in June of 2010 it came to my attention that, although they may be firmly embedded in my consciousness, I had never actually read all of the Narnia books. This struck me as something of an oversight and I resolved to rectify the situation as soon as possible and read them all before the end of the year (which I did, I’m just a little late in posting reviews). After the first four books, I had had quite enough of earnest children solving problems for the time being and was suffering from Narnia fatigue and so set them aside. I had forgotten about completing the series until I saw all the promotional material for the new film of The Voyage of the Dawntreader and being thoroughly irked by it. (Why the strange pronunciation? You don’t say lawn mower or horse rider, you say lawn mower and horse rider with the stress on the first thing, so why on earth would it be Dawntreader?) My irritation gave me the motivation I needed to return to the series.

The Voyage of the Dawntreader is, chronologically, the fifth book in the Narnia series. In it, Lucy and Edmund are drawn into Narnia through a painting, bringing with them their reluctant and sulky cousin, Eustace. Together, the three of them join King Caspian, older now than the last time we saw him in Prince Caspian, as he journeys to the eastern edge of the known world to discover what happened to the men loyal to his father whom his evil uncle sent away on a sea voyage from which none of them have ever returned.

Sadly, The Voyage of the Dawntreader was not my favourite of the Narnia books; that honour, rather unconventionally it seems, belongs to The Magician’s Nephew. The length of the Narnia books does not really lend itself to an epic journey storyline and so I felt that this book was very unevenly paced, with excessive amounts of time devoted to some events while others were skimmed over in a few sentences. Consequently, some of the episodes, such as Eustace and the dragon and Lucy and invisible voices, were excellent and well developed, whereas others felt rushed and perfunctory. I thought that the rapid dismissal of the island of dreams, one of the most interesting ideas in the book, was particularly disappointing. However, although plenty of people write better quest novels than Lewis, it is still an enjoyable read.

I was surprised at how much I liked the development of Eustace’s character, as Lewis manages to show how irritating he is without making him annoying to read about. His indignant diary, his outrage at not being able to contact the British embassy and his stubborn refusal to believe things despite all evidence to the contrary add wonderful touches of comedy to the book. This light relief is particularly welcome as I feel that The Voyage of the Dawntreader represents the point at which the series begins to become more serious: although allegory is an ever-present feature of the Narnia books I felt that it became a lot more overt in this book and there are several dark references to the future of the children and of Narnia itself. Although I didn’t enjoy this book as much as the others so far, I think that it played a necessary role in the trajectory of the series as a whole, and I look forward to seeing what comes next and how Lewis builds on this foundation.

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by C. S. Lewis. Illustrated by Pauline Baynes. Published by Diamond, 1996,pp. 189. Originally published in 1955.

‘Five Children and It’ by E. Nesbit

What do you read when it’s dark and cold outside, it’s an hour of day which no diurnal creature is supposed to see and you have to leave your nice, warm, snug bed and venture out into the snow and ice for the pleasure of spending a day at work, that is if the train ever manages to get you there? Or, slightly less specifically, what are your comfort reads? For me, it’s classic children’s literature. Nothing perks me up quite like reading a good, old fashioned adventure story in which nothing is ever quite as important as supper. They are safe (after all, nothing ever goes drastically wrong in these books) but still exciting, moral but not preachy and humorous without being deliberately funny. Five Children and It by E. Nesbit is the epitome of these qualities for me and is probably my favourite children’s book of all time.

What do you read when it’s dark and cold outside, it’s an hour of day which no diurnal creature is supposed to see and you have to leave your nice, warm, snug bed and venture out into the snow and ice for the pleasure of spending a day at work, that is if the train ever manages to get you there? Or, slightly less specifically, what are your comfort reads? For me, it’s classic children’s literature. Nothing perks me up quite like reading a good, old fashioned adventure story in which nothing is ever quite as important as supper. They are safe (after all, nothing ever goes drastically wrong in these books) but still exciting, moral but not preachy and humorous without being deliberately funny. Five Children and It by E. Nesbit is the epitome of these qualities for me and is probably my favourite children’s book of all time.

Five Children and It tells the story of Robert, Anthea, Cyril and Jane and their baby brother, known affectionately as the Lamb. While holidaying in the country, their parents are both unexpectedly called away for various reasons, leaving the children to entertain themselves all summer. On the first day, they go to play in an old gravel pit and there they uncover a mysterious creature: a Psammead. These sand fairies have the ability to grant wishes which will last only until sunset. However, the old saying that you should be careful what you wish for proves true, and things often don’t work out quite as the children plan as their summer suddenly becomes much less dull and far more fraught with adventure.

There are so many things in this book which I find irresistible. First and foremost, I love the way that the world of the five children is completely conventional with the exception of one strange and magical thing: the Psammead. In fact, the world is so ordinary that the story seems almost believeable, and I remember spending many a day after I first encountered Five Children and It industriously searching beaches and sandpits for any burrowing sand fairies. Although the Psammead grants one wish a day for the children, everything else happens exactly as it would without the magical element. Thus when the children wish to be as beautiful as the day, neither their little brother nor the servants recognise them and they have to beg for food from neighbouring houses and they frequently get into trouble when their escapades keep them out past supper time. Even their wish that the servants won’t notice whatever they wish for, an attempt to avoid getting into trouble, only leads to more disaster and scoldings. In fact, the children’s wishes usually either don’t work out as they might have hoped or lead them into unforeseen scrapes from which they must extricate themselves without being able to explain to any grown ups about the magical happenings which have resulted in these strange situations. This makes for a far more satisfying book, in my opinion. A book that simply chronicled the successful wishes about a group of children might be entertaining if it were well written, but it would be fairly one dimensional. However, a book about wishes that backfire and wishes that aren’t necessarily what you intended is an engaging idea with endless possibilities. The pleasure in reading Five Children and It comes not so much from seeing the children enjoy the results of their wishes but in watching them deal with the unexpected but inevitable consequences of those wishes.

The story is brought to life by E. Nesbit’s wonderful narrative voice which permeates the book. She adopts a conspiratorial tone, as though she is letting the reader in on a big secret which makes the story feel even more special. Her humorous asides on every subject are a joy to read and can be appreciated just as much by adults as by children. She passes judgement on the children, on the adults around them and on grown ups outside the world of the book, but she does so in a way that is never condemning although it is accurate and astute. She invites the reader to share these opinions and so thoroughly draws you into the narrative.

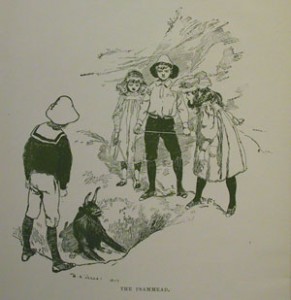

The Psammead itself is a wonderful creation. Although Nesbit calls it a fairy, it definitely isn’t what springs to mind when using the word, as you can see from H. R. Millar’s illustrations from my edition of the book. Fat and furry with eyes on the end of stalks like a snail, it is a thoroughly original creation. It is crotchety and short-tempered (although with good reason, I feel, being pestered daily by five children) and it makes a refreshing change to have an unwilling, grumpy magical creature in a children’s book, rather than one that is obliging. One could almost suspect, as the children do, that the Psammead is wilfully misinterpreting their wishes in order to land them in difficult situations deliberately. The presence of this creature certainly adds to the humour of the book and helps to make it a wonderful read.

The Psammead itself is a wonderful creation. Although Nesbit calls it a fairy, it definitely isn’t what springs to mind when using the word, as you can see from H. R. Millar’s illustrations from my edition of the book. Fat and furry with eyes on the end of stalks like a snail, it is a thoroughly original creation. It is crotchety and short-tempered (although with good reason, I feel, being pestered daily by five children) and it makes a refreshing change to have an unwilling, grumpy magical creature in a children’s book, rather than one that is obliging. One could almost suspect, as the children do, that the Psammead is wilfully misinterpreting their wishes in order to land them in difficult situations deliberately. The presence of this creature certainly adds to the humour of the book and helps to make it a wonderful read.

Reading this book has filled me with the urge to watch the old BBC adaptation of Five Children and It. I’m sure it would look horribly out of date now, but it had a great many virtues in its day (not least of which was teaching me how to pronounce ‘Psammead’) and I’m feeling all nostalgic. Does anyone else remember it?

Reading this book has filled me with the urge to watch the old BBC adaptation of Five Children and It. I’m sure it would look horribly out of date now, but it had a great many virtues in its day (not least of which was teaching me how to pronounce ‘Psammead’) and I’m feeling all nostalgic. Does anyone else remember it?

Five Children and It by E. Nesbit. Illustrated by H. R. Millar. Published by Puffin, 1978, pp. 215. Originally published 1902.

2011 Reading Resolutions

Although I don’t like to feel restricted in what I read, I do like to set myself some goals at the beginning of the year. This year they’re designed to guide my reading, while giving me the maximum flexibility to read exactly what I feel like reading.

The TBR Lucky Dip – You might have noticed a new tab which has appeared at the top of the blog entitled ‘Mount TBR’. This is, as the name suggests, a list of all the books that I own but have not yet read. It is shameful, I know. Each month, I’m going to be using a random number generator to select me a book from my list to read to try to help me read some of the titles I may have forgotten about.

There are a few rules to make things as simple as possible:

- If the chosen book is a later book in a series and I haven’t yet read the preceding book, I instead read the first unread book in that series. If I don’t own the next one that I need to read, I am allowed to purchase it.

- If the chosen book is one that I don’t want to read at that moment in time or is an impractical choice (for example, I’m looking for a book to read on the train to work and the generator selects Infinite Jest) I am allowed a second pick. There’s no sense in making reading a chore rather than a pleasure.

If anyone would like to join me in this monthly venture, please leave a comment and I’ll see what I can set up. It would be great to have other people reading odd things from their TBR piles together with me.

The Victorian Literature Challenge – I’ve already posted about this challenge here and I’m really looking forward to getting stuck in now the calendar has turned over to 2011. My plan is to read one book a month, but we’ll see how it goes. It seems like an excellent way to make myself get around to reading all those dusty classics above my bed.

The Victorian Literature Challenge – I’ve already posted about this challenge here and I’m really looking forward to getting stuck in now the calendar has turned over to 2011. My plan is to read one book a month, but we’ll see how it goes. It seems like an excellent way to make myself get around to reading all those dusty classics above my bed.

My plan is mainly to read novels, but I also have some Victorian poetry and travel writing if I find myself experiencing novel fatigue. I’m particularly eager to introduce myself to Anthony Trollope, who seems to be beloved by bloggers and whom I’ve been assured I will love.

The Women of Fantasy Book Club – I’ve never joined a book club before, but when I saw this one hosted by Erika from Jawas Read, Too! I couldn’t resist. I know I have to read a list of set books, not pick and choose what I like, but these are all books that I wanted to read anyway. January’s pick is The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N. K. Jemisin and the thought that my copy might have arrived at the office from Amazon is making the thought of having to go back to work tomorrow marginally more bearable.

Read more poetry – Reading Christmas Please! throughout December made me remember how much I enjoy poetry. Although I know this in my head, when I go to the shelves to pick up a book to read I rarely if ever select a poetry book and this year I’m going to make an effort to change that. Every month I’m going to choose one book of poems and divide it up so that I have a few poems to read each night before bed. Having bitesize portions of poetry makes it more accessible and should encourage me to read and enjoy more of my poetry books.

Mostly, I just want to enjoy my reading this year as I know it’s going to be quite a busy and possibly stressful time. I can’t wait to see what 2011 will bring.

The End of Year Book Meme 2010

I know I’m a bit later than a lot of other bloggers in posting a summary of my year’s reading, but I wanted to wait until the year had actually ended in case a few more books decided to sneak past the finish line (a fortuitous decision, it turns out, as an unexpected diversion via Glasgow on our flight up to Edinburgh on the 30th meant I devoured another two books). The Old English Thorn and I have just arrived back from a wonderful visit to our friends in Scotland, so this is the first opportunity I’ve had to write up this post.

I was considering how best to wrap up my yearly reading when I stumbled across this meme on Other Stories, Kirsty’s excellent blog. It seemed like an excellent idea, so without further ado I pilfered it and here it is: a summary of my year in books.

How many books read in 2010?

This is the first year since I started recording my reading that I’ve not been in full time education, and I was surprised by quite how big a difference that made to my final reading total. I’ve managed to read 115 books this year, 90 of which I’ve read since I began commuting to London in June. It’s good to see that my train journey has its uses.

Fiction/Non-Fiction ratio?

Unsurprisingly, I’ve mostly read fiction books this year. 107 of them, to be exact. I’ve only managed 6 non-fiction books: one wedding-planning guide, one book about facts, one periodical containing essays about books and three memoirs (but two of those were by Gerald Durrell, so they’re practically fiction anyway). I’m not particularly good at picking up non-fiction and it’s definitely something that I’d like to read more next year.

Male/Female authors?

Apparently this year I have read 57 books by male authors, 55 books by female authors and 5 books either written jointly by male and female writers or anthologising authors of both genders. I’m actually really surprised at how even this is, particularly as it wasn’t something to which I was paying any attention when I chose books this year. I would have expected to read more female authors.

Favourite book read?

I’ve read far too many great books this year to limit myself to just one favourite, so here are a top six (yes, six because I couldn’t wittle it down to five) in no particular order. Even then, it’s a closely fought battle to appear in the rankings.

The French Lieutenant’s Woman by John Fowles – So clever, so elegant, so tricky and yet so readable. This self-aware neo-Victorian novel was never style over substance, but always a perfect blend of the two.

Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson – This gentle book made me smile like nothing else I read this year. It may not be terribly ‘literary’, but it’s sweet and funny and genuinely happy, making it impossible not to love. It was alsomy introduction to the marvellous Persephone Press, a publisher from whom I look forward to reading more this year.

The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins – I was very impressed by Collins’ ability to write in such a wide variety of different voices and make them all distinct, and I loved the gripping mystery.

The Return of the Soldier by Rebecca West – It’s a rare thing that I describe a book as perfect, but that is how I found this book. The prose was like poetry and each word was so carefully considered and expertly deployed. I’m definitely intending to read more of West this year.

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton – Heartbreaking and bittersweet, yet so witty and amusing. I loved this look at forbidden romance in old New York and Wharton’s writing style.

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy – This was my first tentative foray into Russian literature and it blew me away with its scope and insight. For me it was the slow, ponderous Levin rather than mercurial Anna who made the book so great. I read this before I’d started reviewing everything here, but you can read my thoughts on it here.

Honourable mentions go to The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafon, Lady Oracle by Margaret Atwood, Carter Beats the Devil by Glen David Gold and The Little Stranger by Sarah Waters.

Least favourite?

There were a few books I read this year that I didn’t particularly like, but the one book that I loathed with a fiery passion was The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett. It annoys me that a book that is so lauded for being historically accurate is laughably far from being so; it felt bloated, repetitive and unnecessarily long; and the characters read like 20th century people dressed up in faux medieval clothing. But I do recognise that I’m decidedly in the minority with this opinion.

Oldest book read?

I think this honour goes to The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins, first published in 1859.

Newest?

As my books tend to come from charity shops and it takes a while for new books to filter through to them, I would guess that the newest books I read would be the two that I was kindly sent for review: The Breaking of the Shell by Barry Durdant-Hollamby and Oops! Darrell Bain’s Latest Collection of Stories.

Longest book title?

The 13 1/2 Lives of Captain Bluebear – Being the biography of a seagoing bear, with numerous illustrations and excerpts from the ‘Encyclopaedia of the Marvels, Life Forms and Other Phenomena of Zamonia and its Environs’ by Professor Abdullah Nightingale by Walter Moers

Shortest title?

Crash by J. G. Ballard

How many re-reads?

Absolutely none, although I know I’m heading for some in 2011.

Most books read by one author this year?

Thanks to finally deciding to read the Narnia books, C. S. Lewis is way out in front of any other author with 7 books this year.

Any in translation?

This year I read 10 books in translation, which is more than I would have expected. In order of reading they are: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson (Swedish), The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafon (Spanish), The Girl Who Played with Fire by Stieg Larsson (Swedish), La Prisonniere by Malika Oufkir (French), Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (Russian), Death and the Penguin by Andrei Kurkov (Russian), The 13 1/2 Lives of Captain Bluebear by Walter Moers (German), One Hundred Years of Solitue by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (Spanish), Baudolino by Umberto Eco (Italian), The Christmas Mystery by Jostein Gaarder (Norwegian).

And how many of this year’s books were from the library?

Absolutely none as I haven’t been able to use the library this year because of my working hours. I’ve finally sorted myself out with the ability to reserve books from the online library catalogue now though, so that I can either go and collect them at the weekend from the larger library or send my wonderful mother on my behalf.