‘The Salzburg Tales’ by Christina Stead

Well, it’s finally happened: the honeymoon period is over. I suppose the day had to come when I encountered a Virago Modern Classic for which I didn’t particularly care, and it seems that that day is today. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that I actively disliked The Salzburg Tales by Christina Stead, all the more so because I was looking forward to it so much as it sounds like it should be the ideal book for me, being the lover of Chaucer that I am.

Well, it’s finally happened: the honeymoon period is over. I suppose the day had to come when I encountered a Virago Modern Classic for which I didn’t particularly care, and it seems that that day is today. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that I actively disliked The Salzburg Tales by Christina Stead, all the more so because I was looking forward to it so much as it sounds like it should be the ideal book for me, being the lover of Chaucer that I am.

The Salzburg Tales is a 1930′s take on Chaucer’s famous Canterbury Tales, following the same pattern of a group of strangers meeting (in this case they are all attending the opera at the Salzburg Festival) and deciding to tell stories to pass the time. A 1930′s take on The Canterbury Tales? What’s not to love? Well, quite a bit if I’m honest.

For a start, Stead’s characters are nowhere near as diverse and interesting as Chaucer’s are, and I think that’s partly due to the set up of her frame narrative. Chaucer has his characters meet at a pub prior to going on pilgrimage. Boccaccio in his Decameron which follows the same format has his characters fleeing from the black death in Florence. Religion and death are both great levellers of men, but Austrian opera, strangely enough, is not. As a result, Stead’s characters are all the sort of middle class people who might attend an opera festival and so, although she has a keen eye for detail, there are none of the great individuals like the Miller or the Wife of Bath who stand out. Instead, they’re all much of a muchness. I enjoyed the character portraits when reading them, such as the Banker:

He would risk half his fortune on a throw, turn head-over-heels in the air in an aeroplane, tell anyone in the world to go to Hell, laugh at princes and throw tax-collectors out the door, but he suffered excessively from toothache because he feared the dentist’s chair: and he was convinced that his luck depended on numbers, events, persons, odd things he encountered; his head accountant was forced to wear the same tie for six weeks because it preserved a liberal state of min in the Government in a difficult time: his chauffeur was obliged to carry the same umbrella, rain, hail or shine, because the umbrella depressed the market in a stock he had sold short. (pp. 39-40)

Or the Old Lady:

She wore a long gold chain and a lorgnette and an expensive hat made of satin, feathers, straw and tulle, all mixed and mummified together: no one could imagine what antediluvian stock of unfashionable materials had been drawn upon to make her hat. (p. 43)

They have enough interesting quirks to make them interesting without making them too contrived, and this was by far my favourite part of the book. However, the character types are all very similar and so even with these little details it becomes impossible to tell them apart, particularly when they do not behave in any manner distinct to their characters after this introduction.

Because the characters are all very similar, so are their stories. There was none of the variety of tone, dialect, register, interests and agenda which make The Canterbury Tales so great. In fact, I didn’t believe that any of these stories was being told by anyone other than Christina Stead herself. They aren’t the stories of the characters described at the beginning, but merely a short story collection stuffed into an unnecessary framework which adds nothing to the reading and understanding of them. This would have been less of a problem had I found the stories themselves enjoyable, but sadly they really weren’t my cup of tea. Very few of them were satisfying on a narrative level, often feeling either tedious and drawn out or as though a large chunk of the middle were missing in order to leap to a conclusion which didn’t make much sense.

I found this book a very frustrating read because I wanted it to be so good. Has anyone else read this one and had a similar experience? Or have you read it and loved and can explain what I might have missed? I’m a bit disappointed really, not to mention rather intimidated by the other Stead books I have lurking malevolently on my shelves, most of which are worryingly chunky. Are they all going to be like this?

The Salzburg Tales by Christina Stead. Published by Virago, 1986, pp. 498. Originally published in 1934.

‘Alice Hartley’s Happiness’ by Philippa Gregory

There are a lot of authors whose books I can pick up without knowing any specifics but with a fair idea of how the book will go. Dickens? Deserving poor, a host of comedic supporting characters with amusing names, and a downtrodden central character who is elevated through their own goodness. Angela Carter? A twisted, chaotic storyline which never develops quite how you might expect, accompanied by a liberal helping of sex and possibly spiced up with a bit of incest. Philippa Gregory? Bodice-ripping historical romps with a dubious regard for accuracy, compensated for by lots of sex. This is comforting: sometimes I like a surprise, but often it’s nice to know exactly what sort of book I have in my hands before I begin reading. However, some books seem to exist purely to shatter my illusions and to break the authorial mould by being so different from what I associate with an author that I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t read it myself. Alice Hartley’s Happiness is just such a book.

There are a lot of authors whose books I can pick up without knowing any specifics but with a fair idea of how the book will go. Dickens? Deserving poor, a host of comedic supporting characters with amusing names, and a downtrodden central character who is elevated through their own goodness. Angela Carter? A twisted, chaotic storyline which never develops quite how you might expect, accompanied by a liberal helping of sex and possibly spiced up with a bit of incest. Philippa Gregory? Bodice-ripping historical romps with a dubious regard for accuracy, compensated for by lots of sex. This is comforting: sometimes I like a surprise, but often it’s nice to know exactly what sort of book I have in my hands before I begin reading. However, some books seem to exist purely to shatter my illusions and to break the authorial mould by being so different from what I associate with an author that I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t read it myself. Alice Hartley’s Happiness is just such a book.

Alice Hartley is the plump, middle aged wife of a university professor, has a penchant for new age theories, floaty scarves and lots of sex. When she finds out that her husband is having an affair with one of his students, Alice decides that what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander (or vice versa) and promptly drives off in a removal van with one of her husband’s students who has come to collect a desk that he promised to lend the drama group for a play. Not only do they take the desk, but also every other scrap of furniture in the house. They are left with nowhere to put it until Michael’s Aunt Sarah dies, leaving him with her country house. And so begins the establishment of Alice’s growth centre, an alternative, disorganised establishment where sex is free and people are happy.

With the exception of the fact that it still inclused quite a bit of sex, Alice Hartley’s Happiness could not be more different from the usual Philippa Gregory fare. It’s setting is modern, the characters are all unknowns and the tone is light and amusing. The plot is utterly absurd, encompassing everything from unexpected resurrections to dolphin assisted births in the local aquarium, but Gregory acknowledges this and runs with it, resulting in a novel which is not afraid to laugh at itself and have fun while doing so.

For all that her historical novels are light, easy reading, I’ve never found Gregory to be an author who exhibits a particularly pronounced sense of humour, so the wry, detached tone of Alice Hartley’s Happiness is rather surprising. However, it is definitely a welcome surprise; it’s always pleasant to learn that an author suspected of being something of a one trick pony (however enjoyable those tricks may be) is actually rather good at other things too. Take, for instance, the way she introduces Alice’s husband, Professor Hartley:

Professor Hartley was at that time in his life when a man demands of himself what is the meaning of life, asking: ‘For what was I born? And is this all there is? And what of the great quests which have motivated men through the ages? Where am I going? And what is the Nature of Individualism? Or, more simply: Who am I?’

Like all men who courageously confront great questions of identity and truth, Professor Hartley came to one conclusion. Unerringly, untiringly he struggled through his boredom and his despair until he found the source of his discontent, the spring of his angst, his own private darkness. It was all the fault of his wife.

Instantly she conveys how pompous and self-absorbed Professor Hartley is, and the bathos of that last sentence is superb. The humour is all the more enjoyable because it is so unexpected. This surprising change of tone is also apparent in her treatment of sex, which is just as abundant as in her historical novels. However, in this book the sex scenes are silly, improbable and downright funny at times.

If you pick this book up looking for a typical Philippa Gregory novel you are bound to be disappointed. On the other hand, if you turn to it looking for an entertaining and somewhat ridiculous read then it’s actually rather good, and Philippa Gregory continues to fulfil her role as the author of some perfect guilty pleasure reading.

Alice Hartley’s Happiness by Philippa Gregory. Published by Harper Collins, 2009, pp. 257. Originally published in 1992. Also published under the title Alice Hartley and the Growth Centre.

‘Up at the Villa’ by W. Somerset Maugham

Sometimes my reasons for choosing books are incredibly shallow; I bought the Vintage Somerset Maugham collection because of the rather attractive covers (not to mention they were incredibly good value from The Book People, of course), and I chose to read Up at the Villa first because, at a mere 120 pages, it is by far the shortest one of the bunch and I wanted to break myself in gently to this new-to-me author. Both the purchase and the selection were a shot in the dark, made without any prior knowledge other than that Maugham was an author I wanted to try out, and this is one of those fortuitous occasions on which my gamble has paid off remarkably well, as Up at the Villa is a little gem of a novella and reading it has made me excited to carry on with more Maugham (that sounds quite odd if said aloud).

Sometimes my reasons for choosing books are incredibly shallow; I bought the Vintage Somerset Maugham collection because of the rather attractive covers (not to mention they were incredibly good value from The Book People, of course), and I chose to read Up at the Villa first because, at a mere 120 pages, it is by far the shortest one of the bunch and I wanted to break myself in gently to this new-to-me author. Both the purchase and the selection were a shot in the dark, made without any prior knowledge other than that Maugham was an author I wanted to try out, and this is one of those fortuitous occasions on which my gamble has paid off remarkably well, as Up at the Villa is a little gem of a novella and reading it has made me excited to carry on with more Maugham (that sounds quite odd if said aloud).

The story opens rather mundanely, with Mary Panton, a young, English widow spending time in a villa in Tuscany, awaiting a proposal from Sir Edgar Swift, soon to be Governor of Bengal. Although she doesn’t love him, she does not refuse his offer of marriage, but instead asks for the three days that he is away in which to consider her answer. During that time, however, a chance encounter in a restaurant turns her world upside down, and she must choose what to do.

The thing I love about coming to a new author without any expectations is that I never know where exactly the book will go. In this case, when Up the Villa began in a serene, idyllic, rather sweet way I had no idea whether it was going to remain like that and be a pleasant, gentle novella or whether everything was going to be turned on its head (I deliberately refrained from reading the blurb on the back cover and I’m trying to give away as little as possible here too). Maugham creates wonderfully atmospheric scenery which is described in emotional rather than physical terms, leaving no doubt that all is well in Mary’s world as she heads out for dinner:

To dine there on a June evening when it was still day,and after dinner to sit there till the softness of the night gradually enveloped her, was a delight of which Mary felt she could never tire. It gave her a delicious feeling of peace, but not of an empty peace in which there was something lethargic, of an active, thrilling peace rather in which her brain was all alert and her senses quick to respond. Perhaps it was something in that light Tuscan air that affected you so that even physical sensation had in it something spiritual. It gave you just the same emotion as listening to the music of Mozart, so melodious and so gay, with its undercurrent of melancholy, which filled you with so great contentment that you felt as though the flesh no longer had any hold on you. For a few blissful minutes you were purged of all grossness and the confusion of life was dissolved in perfect loveliness. (p. 14)

Can’t you just image yourself there having dinner in the warm, Italian evening sun? This quality of description is maintained throughout the novella and was one of the aspects that I loved.

This could all sound rather earnest, but Maugham has a light touch which laces the book with wry humour, often at unexpected moments. I instantly warmed to Mary, for instance, when she decides:

If he were really going to ask her to marry him, well, it would make it easier for both of them, out in the open air, over a cup of tea, while she was nibbling a scone. The setting was seemly and not unduly romantic. (p. 5)

Mary is a young woman who has been through a lot already and Maugham makes her an excellently well drawn, well rounded character. The reader spends a lot of the book seeing events from her perspective and hearing her thoughts and they never feel inauthentic. Her conversations with Rowley, and English gentleman of dubious morals, reveal her to be astute, self aware and remarkably candid about sex. Perhaps because of her life experience she is under few illusions about herself and what life has to offer her, yet she remains remarkably naive about other things, which is what leads to the events of the story, and this makes her a very interesting character.

All of the characters are surprisingly vivid for such a short novella. Maugham has a way of pinning characters down with just a few words and phrases so that the reader can instantly visualise and understand them, as in the case of the Princess:

The Princess gave him another of those quiet smiling looks of hers in which there was the indulgence of an old rip who has neither forgotten nor repented of her naughty past and at the same time the shrewdness of a woman who knows the world like the palm of her hand and come to the conclusion that no one is any better than he should be. (p. 16)

The pacing of the story is excellent, starting off at the slow, languid speed that you might expect from a novel about the English upper classes in Italy and gradually speeding up until it feels almost out of control. Nonetheless, there are several issues which are left too unresolved for my liking and I wish that there had been just one more chapter addressing these issues and tying up loose ends. That would have made the book nearly perfect. I also found the light, breezy tone of the conclusion rather disturbing, but then I think that’s exactly how I was supposed to feel.

I’ve really enjoyed my first foray into the writing of W. Somerset Maugham through this odd little book. If the rest of the novels I have waiting for me in my collection from The Book People prove half as interesting I can see myself adding even more of his works to my wishlist before the year is out.

Up at the Villa by W. Somerset Maugham. Published by Vintage, 2004, pp. 120. Originally published in 1941.

TBR Lucky Dip: May

As I explained in my post about reading plans for the new year, each month I’m going to be using a random number generator to select a book from my TBR pile for me to read, to help me read more widely from my shelves.

This month, the deities of www.random.org have ordained that I should read book number 775 . According to my TBR list this means that I am reading…

The House in Dormer Forest by Mary Webb

“I suppose, if one could get past your soul and look at your features, you might even be plain,” he said. “But your soul sheds such a light, Amber. I shall never be able to see your features.”

In the depths of Dormer Forest, nestling in a valley, lies Dormer Old House, inhabited by the Darke family, Solomon and Rachael with their four grown children: intense, idealistic Jasper, Ruby, pretty but silly, black-eyed Peter and the off one out, Amber, a girl with a genius for loving – and laughing. There too lives cousin Catherine of the slanting eyes, whose pleasure it is to ensnare men’s hearts. Brooding over all is the great matriarch, Grandmother Velindre, with her religious texts and reprimands, her beady eye upon the five young people in search of love and happiness. As the fate of each unfolds it is Amber who emerges triumphant: one still June morning she is found under a blossom tree by a strange and noble man…

In this, her third novel, Mary Webb examines, with gentle wit and irony, the claustrophobia of intense family life, the crushing of the human spirit by religious and social conventions, and the powers and weaknesses of a woman’s place within them – evoking too, with her characteristic lyricism, the poetic beauty of the Shropshire Forests where all is enacted.

Once again, I’m really rather pleased with my fate at the hands of the bookish number generator. Mary Webb is an author that I’ve been meaning to read for some time as she is one of the writers famously satirised by Stella Gibbons in her novel Cold Comfort Farm. I’ve heard lots of good things about Gibbons’ book (and I have vague memories of seeing it performed as a school play a very long time ago), so it will be good to read some of the source material that inspired it before progressing on to the parody itself. It does suggest that this isn’t perhaps the cheeriest of books, so I’ll try to have something suitably happy lined up for afterwards.

This selection also enables me to tick another book off the Virago list, which is an added bonus.

Has anyone else read this book?

‘Miss Mapp’ by E. F. Benson

Although I only discovered E. F. Benson this year (and I still wonder why it took me so long) he’s fast become one of my go-to writers when I need a comfort read. When I was feeling ill and in need of some cheering recently I turned to the next book in Benson’s Mapp and Lucia series, in which I left behind the familiar sights and residents of Riseholme, even Queen Lucia herself, and instead I met the formidable Miss Mapp for the first time.

Although I only discovered E. F. Benson this year (and I still wonder why it took me so long) he’s fast become one of my go-to writers when I need a comfort read. When I was feeling ill and in need of some cheering recently I turned to the next book in Benson’s Mapp and Lucia series, in which I left behind the familiar sights and residents of Riseholme, even Queen Lucia herself, and instead I met the formidable Miss Mapp for the first time.

Miss Mapp lives in Tilling, a village every bit as concerned with keeping up appearances and being one step ahead of one’s neighbours as Riseholme is. She observes the comings and goings of her friends and acquaintances through her opera glasses from the bay window of her perfectly positioned house and, though she is shrewd (particularly when it comes to schemes for outwitting her neighbours), she frequently misinterprets or misjudges what she sees. Incidents include beating her friend to a new dress, trying to attract the attentions of two retired officers who are far more interested in golf, and attempting to see the king as he goes through Tilling on his train while pretending complete disinterest in his visit.

Although Miss Mapp and Lucia are the same type of character engaged in the same type of activity in the same type of setting, Benson manages to make them impressively different. While Lucia is Riseholme’s undisputed ruler in spite of her flaws, Miss Mapp is on a much more even footing with the residents of Tilling. Consequently, her scheming is more agressive and less good-natured because she has further to go to get ahead of people. She reminds me more of Daisy than she does Lucia. The way Benson ties together her physical appearance and her character is very well done, particularly the way he skirts round using the word ‘fat’:

In spite of her malignant curiosity and her cancerous suspicions about all her friends, in spite, too, of her restless activities, Miss Mapp was not, as might have been expected, a lady of lean and emaciated appearance. She was tall and portly, with plump hands, a broad, benignant face and dimpled, well-nourished cheeks. An acute observer might have detected a danger warning in the sidelong glances of her rather blugy eyes, and in a certain tightness at the corners of her expansive mouth, which boded ill for any who came within snapping distance, but to a more superficial view she was a rollicking, good-natured figure of a woman.

Quaint Irene is an excellent character and a thoroughly welcome addition to the mixture of characters who populate Tilling. She stands out not only for her eccentricities, dressing in boyish clothing (including knickerbockers), displaying socialist tendencies and painting nude portraits of the local fishmonger, but also for her entirely different attitude. Although she enjoys bridge just as much as the next resident of Tilling, unlike the rest she shows no interest in the petty one-upmanships in which they are constantly engaged. She is level-headed and sensible, and her no-nonsense approach provides an effective counterpoint to the silly manoeuvrings and petty squabbles of her fellows. I really hope that she comes to visit Riseholme as I’d love to see how she fits in there.

Although Miss Mapp is easily as entertaining as Queen Lucia and Lucia in London (which remains my favourite so far), it does feel a bit darker, or as dark as you can get within the spectrum of E. F. Benson novels anyway. In Riseholme everyone gets on, for all their grumbles and complaints about each other, but in Tilling the characters will accuse each other of their actions rather than letting them slide. At times it feels nasty rather than gossipy, which is a bit of a change. There are also elements of out-and-out backstabbing between the characters (the incident with the applique dress springs to mind particularly) when they do things specifically to wound another person rather than for the sake of being head of the latest craze or connected to the most important people. Additionally, the outside world intrudes into Miss Mapp more than it does in the previous two books. Riseholme exists in a bubble, whereas in Tilling there are references to new taxes being imposed and to rationing on food and fuel. Money is never an issue in Riseholme, but the population of Tilling are thrifty and worry about paying their bills. It is still a comic novel and the tone is as light as always, but there are more serious undercurrents running through Miss Mapp which I hadn’t expected.

I’m really looking forward to seeing the clash of the titans which is coming up in the next book I have ahead of me, Mapp and Lucia. I wonder who will win, or if the two of them will join forces? If they did, they would be unstoppable!

Miss Mapp by E. F. Benson. Published by Black Swan, 1984, pp. 267. Originally published in 1922.

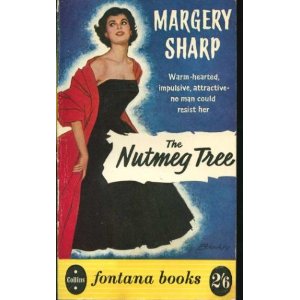

‘The Nutmeg Tree’ by Margery Sharp

How do you arrange the books on your shelves? Do you organise alphabetically by author? By colour of the spine? Do you separate out your TBR pile from the main library? On my shelves, the unread books rub shoulders happily alongside those that I have read, and instead I organise them thematically by vague genre. The fantasy books occupy two bookshelves, the historical fiction another (arranged chronologically of course), and the Viragos are stacked up in one teetering pile down the side of one of the bookcases as I’m swiftly running out of room to accommodate them. Never have I been more grateful for this system of organisation than when I was ill recently and longing for a comfort read which would entertain me without taxing my brain. Right there next to Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson (one of my favourite books from last year) was a dusty copy of The Nutmeg Tree by Margery Sharp.

How do you arrange the books on your shelves? Do you organise alphabetically by author? By colour of the spine? Do you separate out your TBR pile from the main library? On my shelves, the unread books rub shoulders happily alongside those that I have read, and instead I organise them thematically by vague genre. The fantasy books occupy two bookshelves, the historical fiction another (arranged chronologically of course), and the Viragos are stacked up in one teetering pile down the side of one of the bookcases as I’m swiftly running out of room to accommodate them. Never have I been more grateful for this system of organisation than when I was ill recently and longing for a comfort read which would entertain me without taxing my brain. Right there next to Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson (one of my favourite books from last year) was a dusty copy of The Nutmeg Tree by Margery Sharp.

![]() Sharp isn’t an author that I know much about because she seems, entirely undeservedly, to have fallen into obscurity. Although a prolific writer of novels for adults, she is mostly remembered for her children’s books about the two mice called Bernard and Miss Bianca, better known as The Rescuers, and this is probably largely due to the popular Disney adaptations rather than the books themselves. Of all the twenty-six adult books that she wrote only The Eye of Love, published by Virago in 2004, is currently in print. This is a huge shame as, if The Nutmeg Tree is anything to go by, Margery Sharp writes exactly the sort of book I love to read: warm, amusing stories with entertaining characters, written with a light touch and a wry, humorous tone. I’m picking them up in second hand book shops whenever I see them, but some of them (particularly the intriguingly titled Rhododendron Pie) are rarer than hen’s teeth. Hopefully I’ll get hold of a copy one day.

Sharp isn’t an author that I know much about because she seems, entirely undeservedly, to have fallen into obscurity. Although a prolific writer of novels for adults, she is mostly remembered for her children’s books about the two mice called Bernard and Miss Bianca, better known as The Rescuers, and this is probably largely due to the popular Disney adaptations rather than the books themselves. Of all the twenty-six adult books that she wrote only The Eye of Love, published by Virago in 2004, is currently in print. This is a huge shame as, if The Nutmeg Tree is anything to go by, Margery Sharp writes exactly the sort of book I love to read: warm, amusing stories with entertaining characters, written with a light touch and a wry, humorous tone. I’m picking them up in second hand book shops whenever I see them, but some of them (particularly the intriguingly titled Rhododendron Pie) are rarer than hen’s teeth. Hopefully I’ll get hold of a copy one day.

The Nutmeg Tree charts the fortunes of Julia, a middle aged former actress who retains her gleeful love of life and all it has to offer. Her enthusiasm and warmth has got her into trouble before in her youth, not least when she finds herself swiftly become pregnant, married and widowed in the space of a few months. Stifled by the kindness of her very proper and rather rich in-laws, she leaves her daughter Susan with them to be raised and returns to life and work in London. At the start of the novel, Julia has not seen her daughter for sixteen years until a letter arrives from Susan enlisting her mother’s help in persuading her grandparents to let her get married. Unable to resist this cry for help, the affectionate Julia immediately boards a boat for France, determined this time to be a proper mother. But old habits die hard and Julia’s exuberance will not be repressed, particularly when there are eligible gentlemen around.

I could tell that I had picked just the right book as soon as I read the opening paragraph:

Julia, by marriage Mrs Packett, by courtesy Mrs Macdermot, lay in her bath singing the Marseillaise. Her fine robust contralto, however, was less resonant than usual; for on this particular summer morning the bathroom, in addition to the ordinary fittings, contained a lacquer coffee table, seven hatboxes, half a dinner service, a small grandfather clock, all Julia’s clothes, a single-bed mattress, thirty-five novelettes, three suitcases, and a copy of a Landseer stag. The customary echo was therefore lacking; and if the ceiling now and then trembled, it was not because of Julia’s song, but because the men from the Bayswater Hire Furniture Company had not yet finished removing the hired furniture.

Julia is such a character it is impossible not to like her and enjoy reading about her exploits as she tries to appear respectable for the sake of her daughter. If just given the facts about her, she should be someone of whom the reader disapproves: she is far too free with her affections and abandons her young child out of boredom and frustration. Yet Sharp creates her in such a way that her great ability to give love suggests bounty and generosity rather than being a negative attribute, and there is no judgement at all on her decision to leave Susan with the Packetts. If anything, the reader is encouraged to sympathise with Julia’s feelings of being stifled and bored among her interfering but well-meaning in-laws. Her escapades never fail to entertain and bring a smile to my face.

The other characters are all equally enjoyable. I particularly enjoyed the description of Susan’s grandmother:

It seemed to her more likely that her mother-in-law was of the type, not rare among Englishwomen, in whom full individuality only blossoms with age: one of those who, as sixty-one, suddenly startle their relatives by going up in aeroplanes or marrying their chauffeurs…

The story itself isn’t exactly full of surprises; you can tell from the tone of the writing that everything will work out for the best. Sometimes however, the journey is far more important than the destination, and I’ll happily travel along with Julia any day. Sir William talks about feeling a mixture of affection and amusement towards Julia, and that’s exactly how I felt towards The Nutmeg Tree. I really hope that I keep finding her books in the second hand book shops of Charing Cross Road, but more than that I hope that she is rediscovered and reissued so that more people can enjoy her work. With her humour, intelligence and charm she seems like prime Persephone material to me.

The Nutmeg Tree by Margery Sharp. Published by Collins, 1948, pp. 252. Originally published in 1937.

‘Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies’ by Hallie Rubenhold

When I was reading Michael Faber’s novel The Crimson Petal and the White recently, I was struck by the frequent references to the infamous More Sprees in London, a little book detailing the different prostitutes available around the town, where to find them, what they charged and to which particular specialties each one would cater. The chief reason that I was so intrigued by the mention of this book is that, although Faber’s creation is fictional, such books did indeed exist. Perhaps the most famous example of such a volume is Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies which is not Victorian but Georgian, updated each year between 1757 and 1795. During the time that it ran, it sold more than a quarter of a million copies (a huge amount for any book at the time), indicating quite how many men there must have been out looking for a good time in London. It seemed fortuitous then when I stumbled across a copy of Harris’s Book of Covent Garden Ladies: Sex in the City in Georgian Britain by Hallie Rubenhold, which collects the most interesting and diverse entries from various editions of the List, focussing on the year 1793, and compiles them for the modern reader.

When I was reading Michael Faber’s novel The Crimson Petal and the White recently, I was struck by the frequent references to the infamous More Sprees in London, a little book detailing the different prostitutes available around the town, where to find them, what they charged and to which particular specialties each one would cater. The chief reason that I was so intrigued by the mention of this book is that, although Faber’s creation is fictional, such books did indeed exist. Perhaps the most famous example of such a volume is Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies which is not Victorian but Georgian, updated each year between 1757 and 1795. During the time that it ran, it sold more than a quarter of a million copies (a huge amount for any book at the time), indicating quite how many men there must have been out looking for a good time in London. It seemed fortuitous then when I stumbled across a copy of Harris’s Book of Covent Garden Ladies: Sex in the City in Georgian Britain by Hallie Rubenhold, which collects the most interesting and diverse entries from various editions of the List, focussing on the year 1793, and compiles them for the modern reader.

Rubenhold’s edition starts out with an informative and interesting introduction which puts the List into its historical context. Harris’s List was not written by a man named Harris at all, but by an Irish poet named Samuel Derrick who had fallen on hard times and needed to find a way to keep himself out of debtor’s prison. Jack Harris was a notorious London pimp who allowed Derrick the use of his influential name and his extensive list of contacts in return for a one time fee, and so he only became bitter while Derrick became increasingly wealthy.

The entries on each girl provide a surprising amount of detail, and they are often miniature character studies rather than just bawdy adverts promising pleasures. Obviously there is physical description and a summary of which particular tastes a girl caters to along with her prices (as a rule, the more specialised the tastes, the higher the price) but there are also details such as how she came into ‘the public life‘ as the List euphemistically terms it. In some cases, the writer expresses sympathy for a girl who has been led astray by a man and is forced to turn to this particular line of work, as in the case of Miss Char-ton:

This is an old observation, but certainly a true one, that some of the finest women in England are those, who go under the denomination of ladies of easy virtue. Miss C- is a particular instance of the assertion; she came of reputable parents, bred delicately, and her education far superior to the vulgar; yet the address of a designing villain, too soon found means to ruin her; forsaken by friends, pursued by shame and necessity; she had no other alternative, than to turn -, let the reader guess what. – She was long a favourite among the great, but some misconduct of hers, not to be accounted for, reduced to the servile and detestable state of turning common. She is a fine figure, tall and genteel, has a fair round face, with a faint tinge of that bloom she once possessed, is rather melancholy, ’till inspired with a glass, and then is very entertaining company. (pp. 56-57)

In others, girls appear to bring about their own falls through their lusty natures and to thoroughly enjoy doing so, like Miss Jo-es:

This lady was born in the country, but the circumstances of her parents, when she was sufficiently grown up, obliged them to send her into London to get a livelihood, she was not long before she got a place in St. James’s Market, where, whither, by being accustomed to see the poor lambs bleed, or rather a desire of becoming a sacrifice to the goddess of love, is left for the reader to judge, but she was shortly found stabbed to the heart in the most tender and susceptible part of her body, in short she was unable to withstand the powerful impulse of nature any longer, so was ravished with her own consent, at the age of sixteen; her mistress on the discovery, thought proper to send her going, for fear her good man should take it in his head to kill the lamb over again. She began now to show the bent of her inclinations, she listed under the banners of Cupid, and marched at the head, being of a courageous disposition, and always ready to obey standing orders, she had great success, and often made the enemy to yield, by which means she gained no inconsiderable share of spoil, but her charitable disposition, (being always ready to relieve the naked and needy) soon reduced her. (pp. 69-70)

As you can see, this book contains euphemisms a-plenty. At times it felt like reading one of Shakespeare’s dirtier plays, the amount of veiled references to sex, body parts, prostitutes and plenty of less orthodox sex acts there were. As a social and cultural historian this must be a fascinating book to examine.

However, it might not come as a shock to learn that I am not a jolly Georgian gentleman out looking for a good time, and so consequently a lot of these descriptions started to blur into one after a while. They were interesting, and the book itself is fascinating because of what it is, but there were just too many of them without anything to break them up for it to be a riveting read. In the final section of the book which looks at excerpts from outside 1793 the girls are grouped together by type (red heads, foreign beauties, buxom etc.) and I think I might have enjoyed it more had the whole book been arranged like this with some sort of commentary from the author accompanying each section. I know Rubenhold has written two other books on the subject: The Covent Garden Ladies: Pimp General Jack and the Extraordinary Story of Harris’s List and The Harlot’s Handbook, both of which sound as though they are more along those lines, using the List as a means of illustrating a point rather than as the raison d’etre of the book. I’ll definitely be on the lookout for these as this has proven to be an unexpectedly fascinating topic.

Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies: Sex in the City in Georgian Britain by Hallie Rubenhold. Published by Tempus, 2005, pp. 158. First edition.

‘At Freddie’s’ by Penelope Fitzgerald

While I enjoy books of all shapes and sizes I am especially fond of the really fat or the really thin: big, plump chunky books are great because it means I can spend an extended period of time in the same place, really getting to know the scenery and characters, but little thin ones are also excellent because, while I will race through them in a couple of hours, they are usually so heavily concentrated that I will find myself thinking about them and unpacking them for days afterwards, an amount of time disproportionate to their small stature. Given my enjoyment of novellas, I’m not sure how I managed to take as long as I have done to discover Penelope Fitzgerald, who (looking at the size of the books that I have by her sat on my shelves) appears to have specialised in this sort of thing. Feeling in the mood for something less wrist-straining after finishing my enormous hardback edition of The Crimson Petal and the White, I selected a Fitzgerald at random from the pile and so ended up reading At Freddie’s.

While I enjoy books of all shapes and sizes I am especially fond of the really fat or the really thin: big, plump chunky books are great because it means I can spend an extended period of time in the same place, really getting to know the scenery and characters, but little thin ones are also excellent because, while I will race through them in a couple of hours, they are usually so heavily concentrated that I will find myself thinking about them and unpacking them for days afterwards, an amount of time disproportionate to their small stature. Given my enjoyment of novellas, I’m not sure how I managed to take as long as I have done to discover Penelope Fitzgerald, who (looking at the size of the books that I have by her sat on my shelves) appears to have specialised in this sort of thing. Feeling in the mood for something less wrist-straining after finishing my enormous hardback edition of The Crimson Petal and the White, I selected a Fitzgerald at random from the pile and so ended up reading At Freddie’s.

Freddie’s is the name by which the theatre school officially known as the Temple Stage School is referred to by anyone in the know in the 1960′s. Dilapidated and old fashioned, it is kept running by the machinations, scheming and sheer force of will of Freddie, the proprietress. However, but money is needed and times are changing and Freddie must choose either to change with them or remain true to what she knows.

Penelope Fitzgerald has a very light touch. In the hands of a different author this could have been a rather obvious, plot-driven novel in which the children of the school and the famous ex-pupils rally round to save the stage school, presided over by an aged and eccentric Freddie, but Fitzgerald transforms it into something far more subtle about the characters and about the theatre for which the plot is merely a vehicle.

She has an uncanny ability to pin characters down with a few phrases. I knew exactly what the gloomy Irish teacher was like from just the following description:

He had no ability to make himself seem better or other than he was. He could only be himself, and that not very successfully. Meeting Carroll for a second time, even in his green suit, one wouldn’t recall having seen him before. (p. 21)

Who hasn’t wandered out of a job interview feeling like that at some point in their life? It is sharp observations and precise characterisations like this that make the book so enjoyable.

Equally as important as any character in the book is the presence of the theatre itself. Fitzgerald writes about this with wit and humour, and displays both a genuine affection for the stage as well as an awareness of the reality of the work which goes on behind that. At Freddie’s acknowledges the rise of film and television as the dominant form of entertainment and does so with a practical manner which does not excessively romanticise the idea of the stage, something which seems quite rare in theatre books. It displays an equal equanimity towards the disparity between true talent and fame and riches.

I’ve enjoyed my first foray into the works of Penelope Fitzgerald and will be reaching for more whenever I next feel the need for a small but satisfying novella.

At Freddie’s by Penelope Fitzgerald. Published by Flamingo, 1997, pp. 160. Originally published in 1982.

‘The Crimson Petal and the White’ by Michel Faber

I hate to seem prejudiced, but there are certain literary devices which I tend to find very off-putting in a book. The first is present tense narration: logically the action of the book can have taken place in the past or it could be going to take place in the future, but I’m always very aware that it isn’t actually happening right now. This is something particularly evident in the case of historical novels as it patently isn’t 1645 at the moment, for example. My other pet hate is the author addressing the reader directly (I make an exception for Jane Eyre), especially when the reader is spoken to as ‘you’ and the author tells the reader what ‘you’ are doing. I’m always very aware that, no, I’m not walking down a cobbled street and looking at all the shops on either side of me. I’m certainly not doing it in 1645. By rights then, I should have loathed Michel Faber’s doorstop of a Victorian historical novel, The Crimson Petal and the White, employing as it does both of these techniques. However, it utilises them both beautifully, creating a fascinating reading experience and one of the best books that I’ve read so far this year.

I hate to seem prejudiced, but there are certain literary devices which I tend to find very off-putting in a book. The first is present tense narration: logically the action of the book can have taken place in the past or it could be going to take place in the future, but I’m always very aware that it isn’t actually happening right now. This is something particularly evident in the case of historical novels as it patently isn’t 1645 at the moment, for example. My other pet hate is the author addressing the reader directly (I make an exception for Jane Eyre), especially when the reader is spoken to as ‘you’ and the author tells the reader what ‘you’ are doing. I’m always very aware that, no, I’m not walking down a cobbled street and looking at all the shops on either side of me. I’m certainly not doing it in 1645. By rights then, I should have loathed Michel Faber’s doorstop of a Victorian historical novel, The Crimson Petal and the White, employing as it does both of these techniques. However, it utilises them both beautifully, creating a fascinating reading experience and one of the best books that I’ve read so far this year.

As anyone who has seen the recent BBC adaptation of the book will know (I haven’t, for the record), The Crimson Petal and the White tells the story of Sugar, a girl forced into prostitution by her mother the famed brothel keeper Mrs Castaway. Well-read and highly intelligent, Sugar spends her spare time writing a vicious novel in which her protagonist gleefully tortures and murders the men with whom she has sex. Her life changes when she attracts the attentions of William Rackham, the heir to the Rackham Perfumeries fortune who refuses to take an interest in the business until the desire to possess Sugar as his own means that he needs to make money in order to set her up as his mistress. As Sugar becomes totally dependent on William, she also becomes more and more involved in all aspects of his life, from his business to his child-like wife Agnes, to his young daughter Sophie.

The novel opens with this passage, which instantly draws the reader in:

Watch your step. Keep your wits about you; you will need them. This city I am bringing you to is vast and intricate, and you have not been here before. You may imagine, from other stories you’ve read, that you know it well, but those stories flattered you, welcoming you as a friend, treating you as if you belonged. The truth is that you are an alien from another time and place altogether.

When I first caught your eye and you decided to come with me, you were probably thinking you would simply arrive and make yourself at home. Now that you’re actually here, the air is bitterly cold, and you find yourself being led along in complete darkness, stumbling on uneven ground, recognising nothing. Looking left and right, blinking against an icy wind, you realise you have entered an unknown street full of unlit houses and unknown people. (p. 3)

The voice is powerful, cynical, intelligent and utterly absorbing. It acknowledges the problems that quite a lot of readers have with present tense narratives then brushes them aside as unimportant, which is perhaps why I was less bothered by it than I usually am. It is an atmospheric and compelling beginning and the rest of the novel easily lives up to the high expectations that this creates.

Faber is not only brilliant at setting scenes and giving the writing a real period feel, he is also a master of characterisation; although the story may seem a little like the seedy underbelly of a Dickens’ novel, the characters who people if could not be further from Dickens’ enjoyable but often one dimensional charicatures. Faber makes his characters all so distinct with totally different voices and, frequently, some strange quirk which allows them to transcend the stereotype of their role within the book. Sugar, for example, has a skin disease, yet she is still desired by the men of London because it is rumoured that she will do anything. This is not because she is desperate, but because when the reader meets her she genuinely does not seem to care what happens to her outer self as long as she is able to preserve the inner self who writes and plots and schemes. Mrs Castaway is set apart by her peculiar collection of pictures of Mary Magdalen, which she pastes into scrapbooks. Sophie has a perfect childhood logic and solemnity which just leap off the page.

The most fascinating character for me was Agnes, William Rackham’s wife. Never have I read more convincingly written madness. It has its own internal logic which makes it seem completely understandable, even as the reader knows that Agnes is mad. Her attempts to seek solace in the Convent of Health and her abiding, if somewhat off-kilter, Catholic faith are touching as they show how deeply unhappy and unsettled she is in her current life. Her horror and frantic desperation to escape the life she leads, which does not improve after Rackham regains his fortune, are so well drawn that they feel almost tangible. Her madness is interspersed with periods of complete lucidity, when she is possibly even more unhappy, which make her all the more compelling. The way that the reader discovers Agnes along with Sugar through reading her hidden diaries is a clever stroke and helps to bind the reader into their complicity which will become so important.

Given the subject matter of The Crimson Petal and the White and other reviews and comments that I’d read about the sex in the book, I was surprised at how restrained I found it. Although there is a fair amount of sex which is described in detail, it feels clinical and matter of fact rather than graphic and titilating, and it is never gratuitous. Because Sugar and her fellows see nothing unusual or even particularly exciting about the acts that they perform, they come across as rather mundane and this, conversely and rather brilliantly, makes them even more disturbing than if they were luridly detailed encounters designed to be erotic. It is all the more sordid because it is presented as being so normal.

All in all, this is a fabulously written book which evokes the Victorian era through a series of unique characters who fascinate and repel in equal measure. I’m definitely in the market for a copy of The Apple, a collection of stories which fills in some more details of Sugar’s story and follows some of the lesser characters. I only hope it is anywhere near as good as this book.

The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber. Published by Harcourt, 2002, pp. 838. Originally published in 2002.

Commonplace Quotations

Why do cats sleep so much? Perhaps they’ve been trusted with some major cosmic task, an essential law of physics – such as: if there are less than five million cats sleeping at any one time the world will stop spinning. So that when you look at them and think what a lazy, good-for-nothing animal, they are, in fact, working very, very hard.

- Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson