Review: ‘Elementals’ by A. S. Byatt

Title: Elementals: Stories of Fire and Ice

Title: Elementals: Stories of Fire and Ice

Author: A. S. Byatt

Published: Vintage, 1999, pp. 232

Genre: Short stories

Blurb: A new volume of stories from A. S. Byatt is always a joy, and this one is rich and rare indeed. In the same distinctive format as The Matisse Stories and The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye, this collection deals with betrayal and loyalty, quests and longings, loneliness and passion — the mysterious absences at the heart of the fullest lives. A woman walks away from her previous existence and encounters an ice-blond stranger from a secretive world; a schoolgirl draws a blood-filled picture of the biblical heroine Jael; a swimming pool reveals a beauteous monster in its depths. The settings of Elementals range from the heat of Provence in summer to the cold forests of Scandinavia, from chalk-strewn classrooms to herb-scented hillsides, from suburban streets to rocky wilds. A marvelous present for all A. S. Byatt fans, this magical collection will also serve as a perfect introduction to one of our finest contemporary writers. (Goodreads summary)

When, where and why: I picked this book up from a second hand book stall in Winchester last month when I was house sitting for a friend and had run out of things to read. I started it then, but it once I moved back home it had to wait until I was finished with my other evening book before I could continue with it.

What I thought: As with most collections of short stories, some of these were better than others. They were well-linked by the theme of isolation and the elemental focus of the stories and I thought the collection was a coherent one. The prose was beautiful, lyrical and evocative and I look forward to reading some of A. S. Byatt’s longer works (I have Possession on my shelf) as I think that this will be even more evident when the author has a bit more breathing space. Although the stories are very well-written, I got the feeling that sometimes the short story medium was a little too constraining and Byatt strikes me as an expansive writer rather than a concise one.

Crocodile Tears – Immediately following the sudden death of her husband, Patricia flees to Nimes in the south of France. There she meets Nils Isaksen, a Norwegian who says he has also lost his wife and is writing a book comparing Norse traditions with those of southern France. As the encounter each other more frequently, they each face loss in different ways and reach different conclusions as to what they should do.

For me, this is the least successful story in the collection, which is rather unfortunate for the first offering. At 76 pages, it is rather long for a short story and hence it is much less tight than I would have liked, combining too much detail with too much action and so doing justice to neither. I do like the idea behind the story, I just think it would make a much better novella as it feels a bit squashed as it is.

A Lamia in the Cevennes – An artist becomes consumed with capturing the blue of his swimming pool. After it is filled with chemicals to treat for algae, he insists that the contaminated water be drained and the pool refilled at once from the river. However, the river water brings with it a strange snake-like creature who begs the artist to turn her back into a human.

This story was incredibly visual and vibrant; all the descriptions were full of colour and life, allowing the reader to see the world as it is perceived by the artist. I enjoyed the way that the usual progression of the fairytale narrative (human meets strange creature; they kiss; creature returns to beautiful human form and they live happily ever after) was truncated in this instance by Bernard’s artistic sensibilities. He appreciates the Lamia for the unique element of colour she adds to his picture rather than wishing to transform her into something beautiful but ordinary.

Cold - A young and listless princess discovers that she comes alive in the cold when she is tempted out of the castle to dance naked in the snow one night. She is an ice woman. However, when the time comes for her to choose a suitor, she falls in love with a prince from a desert country where the sand is made into glass in huge furnaces. She must find a way to survive away from the ice she loves without melting in this strange land.

This is probably my favourite story in the collection as it is a take on the fairytale, something which I particularly enjoy. Like Angela Carter, my favourite short story writer thus far, A. S. Byatt does this very well; I particularly enjoyed the stunning resolution. The descriptions are full of intricacy and wonder and, whereas Crocodile Tears felt very detached, emotions in this story are elemental, mercurial and often phrased as physical processes, making them seem even more powerful. I love that such a simple story can encompass such complicated themes and emotions.

Baglady - The wife of a company director becomes lost when she embarks on a planned group outing to the Good Fortune Shopping Mall.

This is a welcomely short short story and consequently has a very different pace to the other entries in this collection. Unlike the others, Baglady depicts a single incident rather than a longer time frame. It is energetic and abrupt and I enjoyed seeing Byatt writing without the embellishment that I’ve already come to think of as her style from reading the other stories.

Jael – A woman who now makes adverts for a living remembers being taught the Biblical story of Jael in her religion classes at school (a subject which doesn’t really count). She muses on her school days and what she has brought with her from then to now.

Until I reached the end of this story, it seemed to be meandering without any real direction. Then along came the sudden, sinister ending which neither narrator nor reader is sure is true or not and suddenly it is clear what all the build up is for. A. S. Byatt cleverly weaves together the strands of Bible story, artificial schoolgirl rivalries remembered and current conflict in the workplace so that all work to shed different lights on the eventual conclusion.

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary – A musing on the famous painting by Velasquz, inspired by two disgruntled kitchen maids.

I enjoyed the use of food imagery in this story, the eggs and fishes of Christ and the kitchen maids set against the elaborate dishes taken into the dining room for the upper classes to ignore. The way the Bible story plays out in the contemporary setting is more explicit than in Jael, but in this circumstance it works well. I may have to investigate this painting to see if there are any other allusions hidden in the story.

Where this book goes: This book remains on my shelves along with my other short story collections. I know I’ll definitely revisit Cold and the book is worth keeping just for that one story.

Tea talk: The weather has been turning cold recently and there are days when it feels like we’ve skipped autumn and gone straight to winter (although I will no doubt revise this opinion when winter starts in earnest). On the one hand, this is definitely a bad thing, but on the other it means it’s the season for smoked teas again. I’ve been drinking Russian Caravan this week and enjoying its warm flavour.

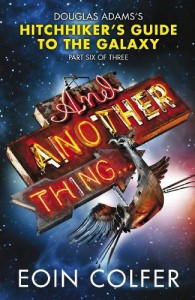

Review: ‘And Another Thing…’ by Eoin Colfer, in the style of Douglas Adams

My husband-to-be has apparently been bitten by the book-blogging bug, and so I have decided to allow him one guest review, on probation. This may or may not become a regular feature…

Title: And Another Thing…

Author: Eoin Colfer (in the style of Douglas Adams)

Published: Penguin, 2010, pp. 340

Blurb: Arthur Dent led a perfectly ordinary, uneventful life until The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy hurled him deep into outer space. Now he’s convinced a cruelly indifferent universe is out to get him.

And who can blame him?

His life is about to collide with a pantheon of unemployed gods, a lovestruck green alien, a very irritating computer and at least one very large slab of cheese. If, that is, everyone’s favourite renegade Galactic President can get him off planet Earth before it is destroyed… again.

When, where and why: I picked this book up last weekend on a trip to Westfield. My English Rose managed to resolutely avoid buying any more books, but this caught my eye. Being a big fan of the series and Douglas Adams, I couldn’t resist picking it up to see how well it worked with a different author.

What I thought: I started this book (billed as part six of three) with high expectations and not a little trepidation. Douglas Adams has a very distinctive style, and I wasn’t sure how well the characters would work in the hands of another author. I have not yet read the Artemis Fowl books that Eoin Colfer is famous for, so I had no idea what was in store.

The story picks up almost immediately after the events of Mostly Harmlessand many familiar characters reappear, including Wowbagger the Infinitely Prolonged, Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz, and Thor. The varying threads of the story flow and intermingle in a very natural way, and there is no shortage of the offbeat fragments that are characteristic of Douglas Adams’ novels.

And the moral of the story is? There are a few actually: some people are bastards and should never be left in charge. And, a Magrathean will always take the money, no questions asked. Finally, always fit composting diaper bags just in case. Because you really never know. No one really ever knows. (p. 35)

I was amazed at how quickly I became drawn into the story, as if it were one of the original series. If I hadn’t known that the book was written by another author after Adams’ death, then I would not have been able to tell. The characters have been beautifully captured and expressed, and the writing style is almost identical.

One new feature in this book is the much more frequent inclusion of relevant (and incidental) notes from the Guide:

Throughout recorded history the ability to ‘state one’s case well’ has generally had about as much success as ‘talking things out reasonably’ or ‘putting aside our differences’. The people who use these tactics generally mean well and would make excellent motivational speakers or kindergarten teachers, but on no account should they be put in charge of situations where lives are at stake. (p. 102)

While it’s nice to have more fragments from the illustrious Guide, it is a double-edged sword. The quotes are usually funny and interesting, but they sometimes interrupt the flow of the tale and distract from the action, and they can span multiple pages. If I had only one criticism of the book, this would be it.

The cover advertises that this edition is “now with added other things”, which form an appendix about the genesis of this book and some history of the series. Having previously only written books for children, Eoin gave a speech at the launch of this book. This is quoted in the appendix, including some brief thoughts about the transition from Puffin to Penguin, and the differences he discovered when writing for an adult audience:

People have asked me, is there much difference between writing for kids/teenagers and writing for adults? I say no, well, you know one is like a lot of fart jokes, you know, a lot of crass humour, and the other one is kids. (Appendix)

Where this book goes: I really enjoyed this book, and I would highly recommend it to any fan of Douglas Adams and the original Hitchhiker’s series. This book is definitely staying on my shelves, and staying nearby for whenever I need some light-hearted and untaxing silliness.

Tea talk: I shall have to be excused from this section. No, really, I have a note from my mum and everything… Well, all right. The simple fact is: I don’t drink hot drinks (apart from the occasional hot chocolate or mulled wine/cider). I shall leave tea to She Who Knows Best instead: my wonderful Old English Rose.

In my mailbox

“In my mailbox” is a weekly meme hosted by The Story Siren in which people share the books that they have acquired that week.

“In my mailbox” is a weekly meme hosted by The Story Siren in which people share the books that they have acquired that week.

This edition actually covers two weeks of book acquisition for me, as I was away last weekend and so didn’t get round to posting. In spite of this, the damage to my struggling TBR pile is remarkably limited. In fact, I’ve acquired an equal number or fewer books in the past fortnight than I have done in any previous week since I began this blog (admittedly, that’s not very many). I’ve nearly managed to read enough books to reduce (if not neutralise) the incoming flow of books, so although Mount TBR is not actually reducing at the moment, at least it’s staying below the ever-looming 500 mark.

From BookMooch I received the following:

- Shadows in Bronze by Lindsey Davis – the second book in an excellent Roman mystery series

- The Crimson Petal and the White by Michael Faber – I’ve had this book recommended to me so many times (apparently I come across as the sort to enjoy books on Victorian prostitution) I was really pleased to get hold of a copy, and it’s a gorgeous hardback too

- Murder with Peacocks by Donna Andrews – This one didn’t stay on the shelf long, and has already been read and reviewed

- Foxfire by Anya Seton – One of the few books from this author that I don’t own, and in an edition which matches my others

- Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue – Another book I’ve been recommended, also about prostitutes

- The Equivoque Principle by Darren Craske – I’ve been enjoying some faux-Victorian mysteries recently and this one looked like it might be good fun

- Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust – It seemed like a good idea at the time

From a local charity shop:

- Death of a Dancer by Caro Peacock – Another faux-Victorian mystery novel

I was also sent a review copy of Oops! Darrell Bain’s Latest Collection of Stories via Goodreads firstreads, which I requested as I enjoy short story collections and this looks to be an interesting selection from a new to me author.

So, in summary:

Books off the TBR pile this fortnight – 5 (plus one audiobook that I haven’t reviewed here)

Books on the TBR pile this fortnight – 9

Change – +3

TBR pile stands at – 495 books

Review: ‘The Last Witchfinder’ by James Morrow

Author: James Morrow

Published: Phoenix, 2006, pp. 573

Genre: Historical fiction

Blurb:In the spring of 1688, Walter Stearne, Witchfinder-General for Mercia and East Anglia, roams the countryside in search of heretics. His daughter Jennet is left behind in the care of her Aunt Isobel, who schools her in the New Philosophy expounded by Isaac Newton. But her aunt’s style of scientific enquiry soon attracts the attention of the witchfinders.

Jennet’s attempts to save her aunt are ultimately doomed, but she promises Isobel that she will devote her life to overturning the Parliamentary Witchcraft Act. Our heroine’s quest will entail many picaresque adventures, including a brush with the Salem Witch Trials, Indian captivity, erotic nights with Benjamin Franklin, a Caribbean shipwreck, and a final showdown between the old superstition and the new science.

When, where and why: I picked this book up several years ago in a wonderful remainders bookshop in Hay-on-Wye where all the books are £1 (I really must go back there soon). I read it now to fulfil the criterion ‘Read a historical fiction book about witches or the trial of witches’ for a book challenge in which I’m participating, and it counts for book 21/50 for my Books Off the Shelf Challenge.

What I thought: This is the book that I wasn’t enjoying to the extent of having to reward myself with another book just to get through it. It has become known as ‘the terrible book’ among friends and family, as that is how the poxy thing was referenced whenever I mentioned it. To put it mildly, I did not get on with this book at all.

My first problem is with the author’s premise that the story of Jennet Stearne has been written by Newton’s Principia Mathematica. I find the idea of books authoring other books to be entertaining, particularly the assertion that:

After Waiting for Godot acquired a taste for writing Windows software documentation, there was no stopping it. (p. 5)

However, amusing as this was, I don’t think that it adds anything to the story. Because the use of the book narrator is supposed to provide a perspective from the modern era on the advances made from Renaissance superstition to Enlightenment rationality (something I’m still not convinced it achieves), it doesn’t have a historical, Newtonian voice and so just sounds like the author putting his oar in every now and again and trying to be literary.

Although Principia claims to be in love with Jennet, the heroine of this book, I didn’t find her to be a very sympathetic character according to its portrayal. She displays near total disregard for her children and for most other people, subsuming everything to the pursuit of her scientific goal. While this may have been intended to make her seem purposeful and single-minded, I thought it made Jennet seem selfish and bloody-minded. It is difficult to relate to a character who discards children, husbands and lovers without much difficulty. As the rest of the characters are very much a supporting cast rather than having anything approaching equal weighting, this made the book a stuggle to read from the outset.

While Jennet is the one central character, she didn’t really have a distinct voice. The same was true for most of the characters; while there were obvious differences between those who championed science and rationality and those who clung to the old ways, no one character had an individual way of speaking or thinking. The groups of characters presented two sides of an argument, and that was all the distinction between them. Equally annoying was the consciously archaic speech. I had barely read a chapter before the constant stream of “i’faith”, “e’en”, “‘sblood” and “’twas” littering the direct speech was wearing thin. ‘Sblood, ’tis a passing wonder I managed to read the whole thing, i’faith.

I think that part of my problem arises from the fact that James Morrow and I evidently have very different attitudes towards historical fiction. In the author’s note he states:

If my experience in composing The Last Witchfinder may be counted typical, then the writer of historical fiction derives no less delight from adhering to the facts of chosen era than he does from bending those facts in pursuit of some presumed poetic truth. (p. 544)

I appreciate that historical fiction is, well, fiction and I have no problems with authors taking some creative licence with actual events as long as they remain believable, particularly where fictional characters interact with real historical figures. I think it’s perfectly reasonable for an author to have his character be a lady in waiting to Queen Elizabeth or a soldier who fought alongside Henry V and spoke to him the night before the battle; having your character be marooned on a desert island with Benjamin Franklin for more than four years, bear his illegitimate son and then devise a plan with him to escape by fooling pirates with science crosses that line of believability just a smidgeon. Initially I was prepared to stretch my imagination and accept that a widow in the late seventeenth century might possess a large and current library and a vast array of scientific paraphernalia including a van Leeuwenhoek microscope, but the plot meanders and stalls and with each unusual circumstance and strangely convenient coincidence I found myself becoming less tolerant and more irritated with the turns the story was taking in the name of ‘poetic truth’.

In spite of the bizarre and implausible storyline, James Morrow has evidently done his historical research (apparently this took him seven years to write). Usually I appreciate a well-researched novel, but this book does not present it in a way which makes the information interesting or relevant. Instead of being woven into the story, it is delivered in large, self-conscious chunks of knowledge by the Principia, as if designed to show off how much research has been done in order to write this book. The other problem with this is that the story was so ridiculous that I don’t really trust any of these facts without double-checking them myself (particularly when the writer states in the author’s note that he has deliberately changed some details) and they are far too many, varied and, quite frankly, dull for me to want to do that.

Where this book goes: I disliked this book so much that I listed it on BookMooch before I had even finished it to provide myself with encouragement to actually finish it now rather than letting it linger with a hundred pages or so to go. Amazingly, someone has requested it already, so it’s been packaged up to send to a new home and to clear some space for other, better books on my shelves.

Tea talk: I keep forgetting to bring some new tea leaves into work with me, so I’ve actually been accompanying this book with coffee (boo, hiss). It was too bad to waste good tea on anyway.

Review: ‘Murder with Peacocks’ by Donna Andrews

Author: Donna Andrews

Published: St Martin’s Paperbacks, 1999, pp. 311

Genre: Contemporary mystery

Blurb:So far Meg Langslow’s summer is not going swimmingly. Down in her small Virginia hometown, she’s maid of honor at the nuptials of three loved ones — each of whom has dumped the planning in hercapable hands. One bride is set on including a Native American herbal purification ceremony, while another wants live peacocks on the lawn. Only help from the town’s drop-dead gorgeous hunk, disappointingly rumoured to be gay, keeps Meg afloat in a sea of dotty relatives and outrageous neighbours.

And, in a whirl of summer parties and picnics, Southern hospitality is strained to the limit by an offensive newcomer who hints at skeletons in the guests’ closets. But it seems this lady has offended one too many when she’s found dead in suspicious circumstances, followed by a strong of accidents — some fatal. Soon, level-headed Meg’s to-do list extends from flower arrangements and bridal registries to catching a killer — before the next catered event is her own funeral…

When, where and why: In spite of my love of books, cats, tea and other traditional trappings of spinsterhood I am in fact getting married next year. In the time between now and then I’ve embarked on a mission to find novels about weddings which actually have a decent plot and interesting characters rather than supposing that excessive amounts of tulle, lace and flowers are suitable substitutes for these. To this end, I’ve been picking up a whole variety of wedding themed books and this one arrived recently from BookMooch (so recently in fact that I’ve not listed it in a Mailbox post yet). I started reading it now because I’m not enjoying my main book very much (review to follow shortly) and I needed a quick read that I could be fairly sure of finding entertaining as a break from that.

What I thought: This is the sort of comfortable mystery which doesn’t make many demands on the reader: the murder victim is sufficiently unknown and unlikeable that the death isn’t distressing; the plot unfolds gently without any dramatic turns; and the solution, while not obvious, is easy enough to work out, even for someone like myself who doesn’t read many mysteries. However, just because it was uncomplicated does not mean it was a bad read, and I thoroughly enjoyed the relaxation of reading this book.

Because the weddings serve as the backdrop for this novel rather than its raison d’etre, I found that it avoided the usual trap of losing plot and characters beneath enormous white dresses. The story, while simple, was good fun and the characters were well-drawn and enjoyable. Narrator Meg Langslow’s array of eccentric family and neighbours added a levity and humour to the standard mystery plot. I was continually amused and how unfazed these residents of small-town Virginia are by the initial murder and continuing attempts on the lives of and her family and friends. Her father is positively delighted at the chance for some amateur sleuthing, Meg’s mother seems oblivious, and Meg herself is more concerned with organising three increasingly demanding weddings.

In Meg herself, Donna Andrews has created a character with a very pleasant narrative voice. She is wry and intelligent and her observations made me chuckle on numerous occasions. Unlike the heroines of many chick lit books, she manages to be single without being either bitter or desperate. She is exasperated by the various brides’ indecisions, demands and dithering without being scathing or dismissive, and the same is true of her attitude towards her family. It makes a welcome change to read a book narrated by someone who is mocking and funny without being sarcastic and unkind.

Where this book goes: I’ve loaned this book to my mother, as I’m fairly sure she’ll enjoy it. After that I think it will be back on BookMooch looking for a new home, as it’s not one I’m ever likely to read again after this year.

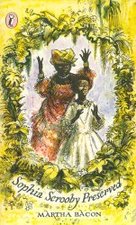

Review: ‘Sophia Scrooby Preserved’ by Martha Bacon

Title: Sophia Scrooby Preserved

Title: Sophia Scrooby Preserved

Author: Martha Bacon

Published: Puffin Books, 1971, pp. 220

Genre: Children’s historical fiction

Blurb: ‘My little panther’, Nono’s father called her, but he didn’t get the chance to say it for long. Her African village was destroyed and she first lived in the bush then was sold as a slave, given a name and a home and then — horrifyingly — sold once more into the hands of pirates. A rich, exciting story about a fascinating and thoroughly believeable character.

When, where and why: I have a nasty feeling that I bought this book when I was the correct age for the target audience, which would make it at least thirteen years old. It has languished on my shelves ever since, so it definitely qualifies for my Books Off the Shelf Challenge. I was prompted to read it now by a challege in which I am participating on Goodreads, one of the criteria of which is to read a young adult book.

What I thought: Some children’s books are so delightful and charming that I love them just as much now as I did when I first read them so many years ago. They have vivid, engaging characters and absorbing stories which draw me in time and time again. Particular favourites are the wonderful stories of E. Nesbitt: The Railway Children and Five Children and It and the subsequent books. Reading Sophia Scrooby Preserved, I got the feeling that I would have really enjoyed it when I was eight or so, but it lacked the elusive magic necessary to translate into a book which I could still enjoy as someone in their twenties.

However, I do think it would be rather unfair to judge this book from my adult perspective when I’m clearly no longer the target audience, as this has all the elements which make for a good, if not great, children’s book. It has a likeable and resourceful heroine in Pansy, as Sophia Scrooby is known, and a series of suitably far-fetched but exciting adventures for her to undertake. It has danger, magic, and history. It has so many of these things that at times they can feel a bit rushed. Nono (as the heroine is initially known) sees her village being destroyed by Zulus, goes to live with a herd of impalas, then journeys to the coast and is sold as a slave without pausing for breath or reflection. As a child, I would probably have found this fast-paced and exciting, but reading the book now I wanted more detail and development.

I thought the pictures throughout the book were a lovely accompaniment to a sweet story, and I would recommend this book as a good historical adventure for readers aged between eight and ten. For me now it was a quick, simple, enjoyable read, but not worth revisiting.

Where this book goes: This book is going off to BookMooch to look for a new home. It wasn’t bad (my usual reason for getting rid of books) but there’s no way I’m ever going to reread this or want to lend it to anyone and as I’m not likely to be spawning for many years it’s definitely not worth hanging onto for future generations to read. It will be good to clear some room on my shelves.

Tea talk: I read this book while sipping some lovely golden Darjeeling. First flush is just starting to be available in the shops now and I’m taking full advantage of that.

Review: ‘The Little Stranger’ by Sarah Waters

Author: Sarah Waters

Published:Virago, 2010, pp. 501

Genre: Historical gothic fiction

Blurb: In a dusty post-war summer in rural Warwickshire, a doctor is called to a patient at lonely Hundreds Hall. Home to the Ayres family for over two centuries, the Georgian house, once grand and handsome, is now in decline, its masonry crumbling, its gardens choked with weeds, its owners — mother, son and daughter — struggling to keep pace with a changing society. But are the Ayreses haunted by something more sinister than a dying way of life? Little does Dr Faraday know how closely, and how terrifyingly, their story is about to become entwined with his.

Where, when and why: I really enjoy Sarah Water’s writing, so I snapped this book up when I saw it on the shelves of a local charity shop a few months ago. The R.I.P Challenge gave me the perfect excuse to read it now, rather than banishing it to the bottom of the TBR mountain.

What I thought: When I started reading this book, I was instantly put in mind of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca which, given how much I loved that novel, can only be a good thing. Sure enough, this book did not disappoint. The Little Strangerhas the same eerie feel, the same crumbling manor house setting, the same complex psychology, and the same basic premise of an outsider breaking into the closed social circles of the landed gentry that has made du Maurier’s work such an enduring classic. In spite of this, Sarah Waters’ book is not in any sense a copycat; it draws on the standard themes of this type of gothic novel and employs them to create a new novel which is fresh, engaging and wonderfully, chillingly open-ended.

It’s very difficult to describe and analyse this book without giving anything away as it is so ambigous. The story concerns the rapidly disintegrating fortunes of the Ayres family and their house, Hundreds Hall, charting their inexorable social and psychological decline at a time of great change in Britain’s history. The book is narrated by Doctor Faraday, a middle aged doctor from a working class background who is the perfect narrator for this story because he is dogmatic, superior and rather dislikeable. His dogged insistance that all the strange events at the hall must have a logical, rational source actually serves to make the reader ever more aware of the possibility that there might not be a reasonable explanation for things, or indeed that he himself is less than innocent.

The chilling uncertainty of the novel is very well balanced. The build up to the strange events is very gradual and the occurance of these events is random so that the reader never knows when the next will happen, creating an atmosphere of suspense. As the novel progresses, these events slowly increase in frequency and develop from being things which are reasonably easy to explain (an old dog biting a young child, for example) into the inexplicable, leaving the reader unsure of exactly what is happening and why. Is the little stranger a ghost? An evil presence brought about through the thoughts of one or other, or possibly even all, of the characters? Is it merely the imaginings of a family of overwrought people struggling desperately to make ends meet? Are they mad? Sarah Waters doesn’t lead the reader to any particular conclusion, but leaves you stranded in your own confused thoughts. I loved this about the book, but I appreciate it isn’t for everyone.

What I enjoyed most about The Little Stranger was that it isn’t just a ghost story or a psychological drama, but also a portrait of the declining fortunes of the aristocracy following the Second World War. Like many others, the Ayres family find themselves inundated with land and a lovely (albeit dilapidated) historic house in which to live, but utterly lacking in money onwhich to live. This is a novel of social history as much as it is of possible paranormal activity, and rather than sitting uneasily side by side, the two aspects are inextricably linked. As the social and economic difficulties for the Ayres family increase, so too do the strange occurrences at the house until the two seem interdependent.

My only quibble with this book, and it is a very tiny one, is related to the narrator. I’ve already mentioned that Faraday is an excellent narrator and character, allowing the novel to have such an eerie feel of ambiguity and suspense, but be that as it may, with the notable exception of Gok Wan I don’t think I’ve ever known or read about a man who pays so much attention to the appearance of the women around him. He notices their complexions; their body types and whether the clothes they wear flatter that shape; their hairstyles and how fashionable they are. Yes, it helps the reader to visualise the characters, but it’s not particularly believable. When listening to the voice of a middle-aged, unmarried, post-war country doctor it is a bit off-putting when it starts to sound like an episode of How to Look Good Naked. However, these descriptions were infrequent enough that they didn’t disrupt my enjoyment. I’m very glad the R.I.P. Challenge prompted me to pick up this book.

Where this book goes: It will be no surprise after reading that review that The Little Stranger is staying put on my shelves along with my other books by Sarah Waters. I hope that it isn’t too long before she writes something else for me to add to my shelves.

Tea talk: This was the perfect book for reading while curled up with a pot of tea on a cold night, and the weather has been rather obliging on that front recently. I’ve been drinking Taylors of Harrogate China rose petal tea, which has a delicate taste and wonderful fragrance which reminds me of summertime and seems an appropriately English flavour to accompany this book.

Review: ‘Memoirs of a Geisha’ by Arthur Golden

Author: Arthur Golden

Published: Vintage, 1998, pp. 434

Genre: Historical Fiction

Blurb: This story is a rare and utterly engaging experience. It tells the extraordinary tale of a geisha – summoning up a quarter century, from 1929 to the post-war years of Japan’s dramatic history, and opening a window onto a half-hidden world of eroticism and enchantment, exploitation and degradation.

Where, when and why: I bought this book in the Oxfam bookshop in the town where I went to university. I think it was around the time that the film came out and I picked up the book because I wanted to read the story before I saw the film. Five years on and I had still done neither until I was prompted to read this book in order to fulfill the ‘Read a book which has been adapted into a movie’ category a reading challenge I’m taking part in on Goodreads. It also counts towards my Books Off the Shelf Challenge and is book 19/50.

What I thought: Memoirs of a Geisha is not so much a novel as it is a love song for a culture and a time that have passed. Reading it, I felt as though Arthur Golden really cared for the culture which nurtured these traditions and was nostalgic for the time of geisha, even though he never experienced it in its heyday. It is a beautifully written book and is very visual; I can see how easily it would translate into film, and I’ve made a resolution to watch it at some point in the future. The book was an interesting read, although the characters and the story were quite clearly only vehicles for Golden to explore and present what life would have been like for a geisha at that time.

Initially, this book reminded me a lot of an 18th century novel in that it takes great pains to fool the reader into thinking that it is true. There is a supposed translator’s note at the beginning from Jakob Haarhuis describing how he met the eponymous geisha and came to record her memoirs, a device designed to give Sayuri a life outside of the confines of her story in the real world and the modern day. The artificial creation of two characters speaking two different through whom the narrative filters before it reaches the English on the page should make the reader distrustful of the reliability of Sayuri’s story as it is so far removed, but instead it heightens the reality and makes the narrative voice seem more immediate. At times, it is as though the character of Sayuri is speaking directly to the reader, as she does to Haarhuis (who is never mentioned outside the translation note). While the account of the life of a geisha in Gion may be far more exciting that Robinson Crusoe’s laboured descriptions of how he finds, picks and dries grapes, once again Memoirs of a Geisha employs an 18th century device in the level of detail Golden includes in the story. Like Daniel Defoe creating Robinson Crusoe surviving on his island, the story of Sayuri feels real because Golden tells the reader about it so thoroughly and recalls such minute things.

The details of the culture, history and rituals of geisha are what makes this book so fascinating. I really enjoyed finding out about something completely alien to me, and I’m interested enough to want to read more. It was my hunger for information which propelled me through the book, as I felt the plot and characters were a bit underdeveloped. With the exception of Sayuri herself, most of the other figures in the books were either sketchy outlines or caricatures, rather than fully realised invidiuals with inner lives. This is partly a result of the faux memoir technique and I think also partly because extra character development would have been unnecessary for — and indeed would have interrupted — Arthur Golden’s exploration of geisha culture. The plot was similarly constrained by what would allow the fullest description of geisha activities and customs. Some areas of the story which were actually quite important in terms of plot, the ending being the obvious example, felt as though they were skimmed over because they didn’t directly relate to Gion and its inhabitants. Consequently, this novel wasn’t gripping but it was still really interesting.

Where this book goes: This book is staying on my shelves in my collection of novels about other cultures.

Tea talk: Rather appropriately given the amount of tea that is drunk in this book, I chose the time when I was reading Memoirs of a Geisha to start on the large round brick of green tea leaves I have in my cupboard. I don’t think I’ve quite got the hang of carving off quite the right amount yet, but I have plenty of tea brick on which to practice.

In my mailbox

“In my mailbox” is a weekly meme hosted by The Story Siren in which people share the books that they have acquired that week.

“In my mailbox” is a weekly meme hosted by The Story Siren in which people share the books that they have acquired that week.

This week was a little worse than last week in terms of book acquisition, and I’m feeling rather guilty. All the other books are looking down at me from the shelves and judging me for not reading them. The historical novels gaze disdainfully down their aristocratic spines at me; the gothic novels glare malevolently; the mysteries brood silently and worryingly; the books about other cultures sniff and mutter about racism; the Victorian novels gaze mournfully and wondering why I continue to buy books when I haven’t read them. Do I not love them enough?

With this guilt generated from anthropomorphising my books in mind, I’m going to make a conscious effort to avoid acquiring any new books this week. My TBR pile has reached ridiculous heights (I’ve promised myself I won’t let it hit 500) and I really don’t need any more books just now. Sadly, with me and books it isn’t a question of needing but of wanting anyway, so we’ll see how my resolve holds out. Wish me luck

This week I received from BookMooch:

- A Spot of Bother by Mark Haddon

- The Reader by Bernhard Schlink

- 84 Charing Cross Road and The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street by Helene Hanff

- Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Ancestors of Avalon by Diana L. Paxson

- The Wedding Day by Catherine Alliott

- Notes on a Scandal by Zoe Heller

And picked up from local charity shops:

- The Greenstone Grail by Amanda Hemingway

- Behind the Scenes at the Museum by Kate Atkinson

- Wedding Tiers by Trisha Ashley

- The Meaning of Night by Michael Cox

- Mary Barton by Elizabeth Gaskell

- Luuurve is a Many Trousered Thing by Louise Rennison

So, in summary:

Books off the TBR pile this week – 3

Books on the TBR pile this week – 12

Change – +9

TBR pile stands at – 492 books

A chilling challenge

Ever since first reading Jane Eyre and then writing my GCSE coursework on the gothic elements in the novel (I’m impressed that I can remember that) I’ve been a fan of gothic literature. Going on to read The Italian by the famous Mrs Radcliffe at university reminded me how much I enjoy these books. After reading Northanger Abbey I realised that I shared Jane Austen’s mocking but affectionate appreciation for the gothic displayed in that book. For me, reading a traditional gothic novel is rather like going to the pantomime: it’s rather camp, slightly silly, very overacted, I’m familiar with the characters and I know exactly where the story is going but I love it nonetheless.

Ever since first reading Jane Eyre and then writing my GCSE coursework on the gothic elements in the novel (I’m impressed that I can remember that) I’ve been a fan of gothic literature. Going on to read The Italian by the famous Mrs Radcliffe at university reminded me how much I enjoy these books. After reading Northanger Abbey I realised that I shared Jane Austen’s mocking but affectionate appreciation for the gothic displayed in that book. For me, reading a traditional gothic novel is rather like going to the pantomime: it’s rather camp, slightly silly, very overacted, I’m familiar with the characters and I know exactly where the story is going but I love it nonetheless.

Consequently, I was very pleased to stumble across the R.eaders I.mbibing P.eril Challenge, now in its fifth year, run by Stainless Steel Droppings. He writes:

Some of my earliest reading memories were collections of Peanuts, borrowed from the local library. I would pour over them, finding humor in the strangest of places, laughing aloud. That early exposure to the work of Charles Schultz cultivated a deep and abiding passion for his creations.And that phrase, “It was a dark and stormy night…” tickled my imagination with thoughts of moonlight and darkness and things that go bump in the night.

Perhaps that was also the beginning of my passion for I what I lump under a broad personal definition of gothic literature: dark nights; decaying, haunted castles; menacing forests; pervasive gloom; ancient prophecies; damsels in distress (or at least at the wrong place in the wrong time); blood-curdling screams…stories with atmosphere so thick you could cut it with a knife.

It was a desire to celebrate and share that love of the elements of gothic fiction that inspired me to create the first R.I.P. Challenge, five years ago.

Readers Imbibing Peril, that is what it is all about. I hope you’ll consider joining us on this more eerie road less traveled.

Walk this way.

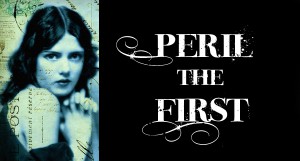

The aim of this challenge is to read books from any of the following genres: mystery, suspense, thriller, dark fantasy, gothic, horror and supernatural. I’m going to aim for Peril the First, which means reading at least four books which meet these criteria.

My intention is to read a mixture of traditional gothic literature along with more modern works. With the exception of The Little Stranger by Sarah Waters which I have already started (and is fantastic, by the way) I’m not sure what I will read yet, but some possibilities include:

- Vathek by William Beckford

- The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole

- The Monk by Matthew Lewis

- The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins

- Sleep, Pale Sister by Joanne Harris

- The Thirteenth Tale by Diane Setterfield

- Echoes from the Macabre by Daphne du Maurier

I shall be keeping a pot of smelling salts on hand in case I am overwhelmed by terror and feel in danger of fainting. All books will of course be read by candlelight while wearing a voluminous nightgown (except when I’m on the train, as that might raise a few eyebrows).