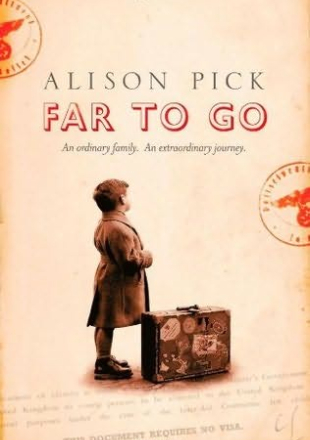

‘Far to Go’ by Alison Pick

Historical novels are usually a staple part of my reading diet, but one that has been rather neglected so far this year in favour of trying new things and branching out into different, unexplored areas of literature. This certainly hasn’t been a deliberate decision and in fact I hadn’t realised that I was reading fewer historical novels until an upcoming title was brought to my attention when I was very kindly offered an advance review copy of Far to Go, a historical novel by Alison Pick set in Czechoslovakia during the Second World War. I feel rather guilty as real life getting in the way means that this review is no longer as ‘advance’ as it should have been, but on the plus side it means you can pick yourself up a shiny new copy of the book almost right away as it’s available in the UK from the 12th of May.

Historical novels are usually a staple part of my reading diet, but one that has been rather neglected so far this year in favour of trying new things and branching out into different, unexplored areas of literature. This certainly hasn’t been a deliberate decision and in fact I hadn’t realised that I was reading fewer historical novels until an upcoming title was brought to my attention when I was very kindly offered an advance review copy of Far to Go, a historical novel by Alison Pick set in Czechoslovakia during the Second World War. I feel rather guilty as real life getting in the way means that this review is no longer as ‘advance’ as it should have been, but on the plus side it means you can pick yourself up a shiny new copy of the book almost right away as it’s available in the UK from the 12th of May.

The inspiration behind Far to Go is Alison Pick’s own family history. Her grandparents were forced to flee from persecution in Czechoslovakia during the Second World War, eventually settling in Canada. She uses this to create the story of the Bauer family, a priviledged Czech family who are Jewish by birth but don’t really practise their faith. However, Pavel, Anneliese and their young son Pepik are Jewish enough to become targets as the Nazi occupations spreads across Europe. The family must try to work out how best to escape and Marta, their non-Jewish nanny, must decide exactly where her loyalties lie.

The Second World War is a subject which is eternally popular (if that’s the right word) in historical fiction and there are a whole host of memoirs and autobiographies from that time, so a book has to try rather hard to stand out amongst so many voices. Far to Go succeeds because it has a different situation and a different tone to other books that I’ve read in a similar vein. Where other novels of the Holocaust can be beautifully, elegiacally tragic, bleakly depressing or even ultimately hopeful, Far to Go feels unusually dirty and distasteful in a way which is extremely effective. This is not a straightforward book but one filled with complex emotions: it is about betrayal which is ultimately understandable, divided loyalties with no possible solution, the physical ache of regret, and bitterness rather than tragedy. The atmosphere is particularly well created.

The novel also deals with an aspect of the Holocaust which I’ve not really read about before, most of the books I’ve read being set in Germany. Pick illustrates well how different the situation was in Czechoslovakia, showing the conflict between Germans and Czechs as a more complex level underlying the usual Nazi/Jew dichotomy. She also chooses to make her characters a family of secular Jews, and in doing so she is able to explore such a variety of different reactions to the persecutions: Pavel becomes more Jewish, driven to explore the faith which makes him an outcast; Anneliese is desperate to throw off the stigma of Jewishness and escape, and Marta the gentile nanny is forced to see her employers in a totally new light. Marta’s struggle to decide what to do in her situation comes across as very real and human, and I like the fact that she is neither a saint with no thoughts for her own security nor a selfishly motivated traitor. I’m sure there were many people who felt exactly as Marta did and were just as confused about their sudden change in status, so it feels very believable.

For all its interesting new perspective, this book is not without its flaws. The four different strands of narrative in quick succession which open the book (a letter from one character, a letter which it’s only later possible to tell is from a different character, a brief first person section with an unidentified ‘I’ and ‘you’, and the main body of the story in third person with different characters again) are initially very confusing. It’s impossible to tell if these people are all the same, partially the same or all different and there’s no obvious features to link the four sections together. It is only as the reader progresses through the book that it becomes apparent who is being referred to in each of them, and while this technique can be effective, I found it to be a few too many things at once with which to open a novel. This mixed structure continues throughout, and while the inclusion of the letters is particularly poignant, I found that it held me at arms’ length from the characters and their actions. I watched them experience these powerful emotions and although the overall emotional tone of the book was impressively well drawn, as I’ve already stated, I didn’t find myself feeling along with them but observing from a distance.

The other niggle that I had was the use of Czech words and phrases. The way that they’re sprinkled throughout the text is actually a rather nice touch as it grounds the novel very firmly in one specific place and adds an authentic flavour of Czechoslovakia. However, the terms used are rarely explained within the context of the story, and having no experience at all of Czech language, Czech food or Czech cutlure I had no idea what all these things being talked about were. I know that lengthy explanations can sometimes be tedious and laboured to read and if they are words that Pick is used to using because of her Czech heritage then it may just not have come up as an issue, but at least the first time a Czech term occurs it would be nice if there were some sort of explanation of what it means without me having to resort to constant Googling. The simple expedient of adding a glossary to the end of the book would solve this problem wonderfully.

Far to Go by Alison Pick. Published by Headline Review, 2011, pp. 314. Advance review copy.

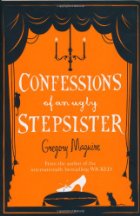

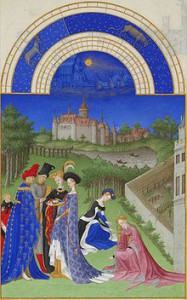

‘Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister’ by Gregory Maguire

Gregory Maguire is an author probably best known for his adaptation of The Wizard of Oz, Wicked. I’ve read the entire trilogy, with somewhat mixed results: Wicked itself I enjoyed and thought it was quite clever (although I imagine that musical is a bit less political and less bizarre than the novel, given how successful it is) but the series became increasingly strange and peculiar and much less enjoyable. A Lion Among Men was downright weird and I found it insufficiently connected to the original story of Dorothy to have much appeal. I think I like the idea of his books more than I like the books themselves, but the concept is so appealing that somehow I find myself going back for more even though they usually leave me unconvinced. It was with trepidation then that I approached his Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister, Maguire’s retelling of the classic fairy tale Cinderella. However, I was pleasantly surprised to find that this book, unlike his others that I’ve read, was a straightforward historical novel with touches of otherworldliness which worked beautifully to enhance the story rather than to make it strange and off-putting. Maguire took a familiar story and retold it in a way which made it new and interesting again, and that was exactly what I was hoping for.

Gregory Maguire is an author probably best known for his adaptation of The Wizard of Oz, Wicked. I’ve read the entire trilogy, with somewhat mixed results: Wicked itself I enjoyed and thought it was quite clever (although I imagine that musical is a bit less political and less bizarre than the novel, given how successful it is) but the series became increasingly strange and peculiar and much less enjoyable. A Lion Among Men was downright weird and I found it insufficiently connected to the original story of Dorothy to have much appeal. I think I like the idea of his books more than I like the books themselves, but the concept is so appealing that somehow I find myself going back for more even though they usually leave me unconvinced. It was with trepidation then that I approached his Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister, Maguire’s retelling of the classic fairy tale Cinderella. However, I was pleasantly surprised to find that this book, unlike his others that I’ve read, was a straightforward historical novel with touches of otherworldliness which worked beautifully to enhance the story rather than to make it strange and off-putting. Maguire took a familiar story and retold it in a way which made it new and interesting again, and that was exactly what I was hoping for.

The story is set in Holland in the 16oo’s, against the backdrop of the tulip boom. The eponymous ugly stepsister is Iris, a young girl who flees from England to Haarlem with her mother, Margarethe, and silent sister Ruth. Once there, they find the family that they expected to take them in are dead and so the family take up work as housekeepers in a painter’s studio in order to survive. When a rich businessman comes to commission a painting of Clara, his beautiful daughter, with some of his prized tulips Margarethe sees the opportunity for advancement and acts to unite her poor family with Clara’s rich one. But, as in all fairy tales, all is not entirely as it seems and plans go awry.

Often when books choose to take an alternative perspective on a well-known story it is to show that character in a more sympathetic light, so I was surprised by the very balanced way in which Maguire presents Iris and indeed all his characters. Iris is downgraded from ugly to merely plain, she cares for her disabled sister, tries to befriend Clara and is credited with intelligence, but she is headstrong (and not in the pretty, charming way that a lot of heroines are headstrong), sullen and uncooperative. Maguire hasn’t made her seem nice, he has made her seem real and believeable. Clara, the Cinderella figure, is likewise knocked down from her fairy tale princess pedestal and into the realms of mere humanity. She is beautiful and intriguing, yet on the other hand she is fey, neurotic and unable to accept things outside of her own terms. Where Cinderella’s beauty traditionally liberates her from a life of drudgery, Clara is very aware that she has very little control over her own fate in spite of her attractive appearance, something which makes the schemes of Margarethe, the wicked step-mother, seem more reasonable and justified and imbues her with a steely resolve that is more driven by self-preservation than cruelty. Ruth, the second sister, is by far the most interesting character despite playing an ostensibly minor role in the story; readers of fairy tales will know never to trust appearances and Ruth does not disappoint.

The choice to place the story in the context of the tulip mania of the 1600′s, when tulips became so popular that a single bulb could sell for more than ten times the annual wage of a skilled labourer, is a clever one. As Clara’s family soon learn to their peril, the tulips had no inherent worth and the speculation which had artifically inflated their price was all an illusion and so the setting encourages questions about true value, worth and beauty which are particularly fitting for the story. Why should Clara be considered worth more than Iris just because she is aesthetically pleasing and Iris is plain? Why is Clara’s father happy to use his shy daughter as promotional material for his business venture? Is value inherent or something subjective that the beholder or buyer adds? It definitely provides an interesting background against which to read the story of Cinderella.

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister by Gregory Maguire. Published by Headline Review, 2008, pp. 397. Originally published 1999.

One Book, Two Book, Three Book, Four… and Five…

I don’t usually post at the weekend, but I’ve really enjoyed seeing this bookish list popping up all over my Google Reader, started by Simon from Stuck in a Book. I love a chance to be nosy and see what other people are reading and buying, so I thought I would join in too. Besides, it seems like a lovely diversion from the task of finishing up making wedding invitations and is a chance to give my aching glue-roller arm a much-needed rest.

1) The book I’m currently reading:

Wild Swans by Jung Chang – I’ve had this book for years and I have no idea why it’s taken me so long to get round to reading it. The story it tells is absolutely fascinating and I feel as though I’m learning a lot about China. I’ve got about a quarter of the book left to go and I’m wondering what more can happen to Jung and her family and how they get to a stage where she’s living in the west writing books.

2) The last book I finished:

The Prince of Mist by Carlos Ruiz Zafon – I picked this one up brand new for a change from a Waterstones in Bournemouth when I shockingly found myself without a book. It’s short but atmospheric and, though I think The Shadow of the Wind was better, I tore through it in a day and rather enjoyed it.

3) The next book I want to read:

I’m hopeless at deciding in advance what I want to read next and by the time I’ve finished Wild Swans I’ll probably plump for something completely different, but at the moment possibilities include Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson, Lady Audley’s Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon, The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood and Black Swan Green by David Mitchell. Any thoughts on which I should try? Or perhaps something completely different. Who knows?

4) The last book I bought:

Wedlock: How Georgian Britain’s Worst Husband Met His Match by Wendy Moore – I picked this up in a charity shop yesterday as it’s a book I’ve been after for a while and it will help with my aim of reading more non-fiction this year. And it’s vaguely wedding related, although I have much higher hopes for my husband than this, it has to be said!

5) The last book I was given:

The Jane Austen Handbook: Proper Life Skills for Regency England by Margaret C. Sullivan – I was recently sent a copy of this book by Quirk Books and it’s a beautiful little volume, containing such invaluable advice as ‘How to buy clothing’ and ‘How to avoid dancing with an undesirable partner’. It has lovely illustrations too, which makes it even more attractive. I can’t wait to get started and learn how to be a proper Regency lady.

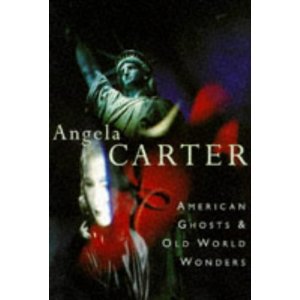

‘American Ghosts and Old World Wonders’ by Angela Carter

Sometimes reading books can be a bit like following the clues to a treasure hunt, one book leading you on to find the next, and that’s exactly what happened to me with this book. Reading Bill Willingham’s Fables: Legends in Exile made me think about other fairy tale adaptations that I’ve enjoyed, which instantly put me in mind of one of my favourite writers of reinterpreted fairy tales, Angela Carter. I first encountered Angela Carter’s writing in my first year of university. I shuffled into the introductory lecture on postmodernism, not exactly eagerly anticipating it after the preparatory reading we had been set, and the handout that came round included a photocopy of Carter’s short story ‘John Ford’s Tis Pity She’s a Whore’. Prior to university I had read voraciously but traditionally, and this story was like nothing I’d ever read before. It was clever and witty and unexpected and I fell in love with it. I bought American Ghosts and Old World Wonders because it contains this particular story but, like a great many of my books, I never got round to reading it all the way through. Now, with the urge to read Carter having been firmly implanted in my mind, it seemed like the perfect time to dust off this book and read it.

Sometimes reading books can be a bit like following the clues to a treasure hunt, one book leading you on to find the next, and that’s exactly what happened to me with this book. Reading Bill Willingham’s Fables: Legends in Exile made me think about other fairy tale adaptations that I’ve enjoyed, which instantly put me in mind of one of my favourite writers of reinterpreted fairy tales, Angela Carter. I first encountered Angela Carter’s writing in my first year of university. I shuffled into the introductory lecture on postmodernism, not exactly eagerly anticipating it after the preparatory reading we had been set, and the handout that came round included a photocopy of Carter’s short story ‘John Ford’s Tis Pity She’s a Whore’. Prior to university I had read voraciously but traditionally, and this story was like nothing I’d ever read before. It was clever and witty and unexpected and I fell in love with it. I bought American Ghosts and Old World Wonders because it contains this particular story but, like a great many of my books, I never got round to reading it all the way through. Now, with the urge to read Carter having been firmly implanted in my mind, it seemed like the perfect time to dust off this book and read it.

American Ghosts and Old World Wonders was published after Angela Carter’s death from lung cancer in 1992 according to directions that she left. The book is a collection of nine stories, four set in the new world of America and five in the old world of Europe. Part one contains ‘Lizzie’s Tiger’, ‘John Ford’s ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore’, ‘Gun for the Devil’ and ‘The Merchant of Shadows’ and part two comprises ‘The Ghost Ships’, ‘In Pantoland’, ‘Ashputtle, or The Mother’s Ghost’, ‘Alice in Prague, or The Curious Room’ and ‘Impressions: The Wrightsman Magdalene’. The new world stories have a more defined story to them, while the old world stories are more abstract and bizarre, although nowhere near as odd as I found Fireworks when I read it last year. The balance between the two halves of the book and the two different styles works well and it forms a good, coherent collection (unsurprising given how specifically Carter planned the contents of the book).

Two stories stick out in my mind from this short story collection and they are, interestingly, the first two in the book. ‘Lizzie’s Tiger’ is about a young Lizzie Borden, who became famous for allegedly killing her father and stepmother, escaping for one evening from her poverty-stricken home to go to visit a nearby fairground. Lizzie is depicted as a serious little girl and Carter uses a wonderful phrase to describe her, saying that she has ‘a whim of iron’. It’s just perfect because it encapsulates the arbitrary nature and forcefulness of childhood desires, and I’m sure anyone who has ever met a child will be able to picture exactly what Carter means. It is impossible to read the story without it being shadowed by the knowledge that this isn’t an ordinary little girl but one who later possibly commits a double murder with a hatchet, and Carter plays on that to change a story of a girl visiting a fairground and seeing a caged tiger into something altogether more sinister and unsettling. Although the story follows Lizzie she never speaks, but only observes in a way that becomes increasingly eerie as the tale progresses, so by the time she encounters the tiger there are obvious parallels between the two of them: both caged, whether literally or figuratively, both potentially lethal and both biding their time for now. I think Carter has written at least one other story about Lizzie Borden, so I’ll definitely be investigating that to see what she does with the interesting character that she has created.

My other favourite was the story which caused me to buy the collection in the first place: ‘John Ford’s Tis Pity She’s a Whore’. In this contribution, which is part story, part playscript, Carter plays on the fact that John Ford is the name of both a Jacobean dramatist and a maker of 20th century western films, combining the two forms to relocate Jacobean Ford’s Italian play ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore’ to the prairies of North America, using setting and characters more at home in one of 20th century Ford’s westerns. It’s such a simple idea but so clever and effective and I loved it just as much this time as I did when I first read it sat in that lecture hall. If you read anything by Angela Carter, read this story.

American Ghosts and Old World Wonders by Angela Carter. Published by Vintage, 1994, pp. 146. Originally published 1993.

‘Fables: Legends in Exile’ by Bill Willingham

With the exception of the Asterix books which I’ve loved since I first borrowed them from the library as a child, my experience with graphic novels has been rather limited. By limited, I mean nil. Partly I think this is because I’ve always been a bit unsure of the concept: pictures are nice enough, but what attracts me to books is the writing, which is dramatically reduced in a book of this nature. However, I had heard so many good things about the Fables books by Bill Willingham that my interest was piqued. I’m a sucker for a good fairy tale adaptation, so I pounced on the first installment, Fables: Legends in Exile, popped up on BookMooch I thought it would be worth a try. Turns out that it was a smart decision, as this was a great introduction to the world of the graphic novel.

With the exception of the Asterix books which I’ve loved since I first borrowed them from the library as a child, my experience with graphic novels has been rather limited. By limited, I mean nil. Partly I think this is because I’ve always been a bit unsure of the concept: pictures are nice enough, but what attracts me to books is the writing, which is dramatically reduced in a book of this nature. However, I had heard so many good things about the Fables books by Bill Willingham that my interest was piqued. I’m a sucker for a good fairy tale adaptation, so I pounced on the first installment, Fables: Legends in Exile, popped up on BookMooch I thought it would be worth a try. Turns out that it was a smart decision, as this was a great introduction to the world of the graphic novel.

The characters from the fairy tales that we all know and love have been driven out of their fantasy world by a sinister unknown enemy. Unable to return to their homes, they are now living in modern day New York City where they try to blend in under the watchful eye of Snow White. Problems arise when Snow White’s sister, Rose Red, goes missing and her aparetment is found covered in blood. While she works with Bigby Wolf to solve the mystery, Prince Charming is attempting to raffle off his kingdom in the old world to raise some much needed money, and evertyhing comes to a head at the traditional Remembrance Day ball.

This is a cleverly written book because, while it has a plot that is neatly tied up at the end, it also provides only tantalising hints into the wider story which surrounds the fairy tale characters. I want to know what exactly happened to their world which made them flee to ours, and how that is going to develop. I want to know more about the characters and their somewhat strained existence rubbing shoulders with ordinary humans. I want to find out more about their traditions and cultures and how their fary stories continue to be played out in the real world. . In other words, it provided the perfect amount of story to engage and satisfy me if I only ever read Legends in Exile, but at the same time it guarantees that I’m going to want to carry on and read more of the series because I’m so fascinated with the world.

This is a cleverly written book because, while it has a plot that is neatly tied up at the end, it also provides only tantalising hints into the wider story which surrounds the fairy tale characters. I want to know what exactly happened to their world which made them flee to ours, and how that is going to develop. I want to know more about the characters and their somewhat strained existence rubbing shoulders with ordinary humans. I want to find out more about their traditions and cultures and how their fary stories continue to be played out in the real world. . In other words, it provided the perfect amount of story to engage and satisfy me if I only ever read Legends in Exile, but at the same time it guarantees that I’m going to want to carry on and read more of the series because I’m so fascinated with the world.

The concept is interesting (if a bit self-consciously silly at times) and it’s much grittier than I had expected from a fairy tale adapt ation. I loved the little details that Willingham puts in about the characters: the Beast, for example, is only handsome as long as Beauty is happy in their marriage, so he keeps reverting to his beastlike appearance every time Beauty becomes annoyed with him (which happens quite frequently). The pictures aren’t as pretty as I tend to favour, but I think they really suit the detective noir style of the story.

This is a great beginning to what promises to be a really interesting series, and one I’ll be continuing with soon, I think.

Fables Volume I: Legends in Exile by Bill Willingham, illustrated by Lan Medina, Mark Buckingham, Steve Leialoha and Craig Hamilton. Published by Vertigo, 2002, pp. 128.

April Summary

Well, so much for my plans to be back on track with reviews by the beginning of May: April is well and truly over and I’m further behind than ever! There seems to have been so much going on in the real world this month, including three amazing burlesque shows, two entertaining theatre trips, two satisfying says making our wedding invitations and one nasty visit to the dentist, that blogging just hasn’t really happened and I’m not quite keeping up. I did manage to review most of the books that I read as I went along, so once I get those awkward, lingering March reviews out of the way I’ll finally be caught up and can move on to the new month’s books.

Well, so much for my plans to be back on track with reviews by the beginning of May: April is well and truly over and I’m further behind than ever! There seems to have been so much going on in the real world this month, including three amazing burlesque shows, two entertaining theatre trips, two satisfying says making our wedding invitations and one nasty visit to the dentist, that blogging just hasn’t really happened and I’m not quite keeping up. I did manage to review most of the books that I read as I went along, so once I get those awkward, lingering March reviews out of the way I’ll finally be caught up and can move on to the new month’s books.

I also mostly kept to my resolution to read larger books this month (though a bout of feeling sorry for myself did mean that some smaller books snuck in here and there), and although I read a 4,387 pages this month which is a similar figure to last month this was spread over only 13 books, averaging 337 pages each (362 if you don’t include the tiny 46 page poetry book that I read). I decided to do this last month in the hopes of reading meatier books that would be more absorbing, and that’s by and large been successful. Although I haven’t had a five star read in April I’ve had a lot of books that have been worth four stars and the rest have been three stars, so it’s been a very good month in terms of bookish enjoyment. In reading order, the books I read in April are:

- Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens

- Perfume from Provence by Lady Winifred Fortescue

- Dawn Chorus by Joan Wyndham

- The Circle Cast by Alex Epstein

- Death of a Naturalist by Seamus Heaney

- The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot

- The Pigeon by Patrick Suskind

- Golden Bats and Pink Pigeons by Gerald Durrell

- Wedding Tiers by Trisha Ashley

- Our Tragic Universe by Scarlett Thomas

- Alexander’s Bridge by Willa Cather

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

- The House at Riverton by Kate Morton

The Mill on the Floss is a book that I’ve tried to read twice before now several years ago, but somehow I’ve never managed to make my way through to the end. When I picked this one up again there was a bookmark at page 139 marking the furthest I’d ever got with it and I was determined not to let it defeat me again. My decision to persevere turned out to be a fortuitous one in this case, as I fell in love with George Eliot’s writing which was so engaging it almost (but not quite) made up for the horrible way the plot developed. I have Middlemarch waiting on my shelves and hopefully I’ll be able to knock it off the TBR pile and into the main library by the end of the year.

This month has been a good one in general for the Victorian Literature Challenge, as I also read Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Victorian writers rather lend themselves to my aim of reading longer books), both of which I enjoyed. I’ve discovered that, while Dickens is verbose and his characters tend towards caricatures, I usually enjoy him more than I think I’m going to, and that I vastly prefer the Sherlock Holmes Short stories compared to the full length novels that I’ve read about the character before. He’s far less irritating in small doses.

Other favourites from this month included the charming memoir by Lady Winifred Fortescue Perfume from Provence which has me longing to visit the south of France and Dawn Chorus by Joan Wyndham which is part family history and part memoir. Both books have me wishing that I kept diaries, but then I remember that a) I don’t live in the south of France or a stately home, b) my diary would read “Woke up stupidly early, spent two hours on the train, went to work, spent two hours on the train, went to gym, came home” for five days out of the seven, and who wants to read that? and c) it would only be another thing to have to keep up to date with writing.

In terms of book acquisitions, this has been a very modest month, mostly thanks to the tail end of Lent which, unlike last month where I had a few slips, I managed to adhere to properly. I put in a book order online on Easter Sunday to celebrate, so no doubt I’ll have plenty of new books to talk about in May as they start to trickle in. However, one book somehow got separated from the rest of the order and made it through before England shut down for the bank holidays, so I have a very speedy copy of They Tied a Label on My Coat by Hilda Hollingsworth waiting to be read now. It’s a memoir of a girl who was evacuated during the Blitz and promises to be a good read.

My copy of the latest Persephone The Sack of Bath by Adam Fergusson which I had pre ordered for £1 back in February arrived at the beginning of the month. I haven’t read it yet, but it looks interesting and very short, if quite different from a lot of the other Persephone books that I’ve come across. I’m saving it for a time when I’m in the mood for some non-fiction. Also arriving out of the blue was a review copy of the latest Scarlett Thomas novel, Our Tragic Universe. I won this from LibraryThing Early Reviewers back in January and had all but given up hope of it arriving when it finally turned up mid way through April. I got stuck in straight away as I’d been dying to read it since I first saw it in hardback, so a review is already on its way.

Amazingly, that’s it for this month! No one is more shocked than I am, I assure you.

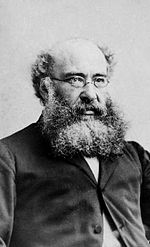

Review: ‘The Warden’ by Anthony Trollope

In a world where there are too many wonderful books to be read and too little time in which to do so, I always welcome recommendations of books that I might enjoy. One such book was The Warden by Anthony Trollope which was recommended to me by a friend who told me to read The Warden and then afterwards to read Barchester Towers regardless of whether or not I enjoyed it because that one was so much better. Dutifully, I went out and got myself a copy — in fact, I’ve somehow ended up with three — and sure enough, I am a Trollope convert (not to be confused with a converted trollop, I hasten to add). It also fits in rather nicely with the Victorian Literature Challenge and, although it is my fourth book towards the challenge, it is the first ‘traditional’ Victorian novel that I’ve read so far this year.

In a world where there are too many wonderful books to be read and too little time in which to do so, I always welcome recommendations of books that I might enjoy. One such book was The Warden by Anthony Trollope which was recommended to me by a friend who told me to read The Warden and then afterwards to read Barchester Towers regardless of whether or not I enjoyed it because that one was so much better. Dutifully, I went out and got myself a copy — in fact, I’ve somehow ended up with three — and sure enough, I am a Trollope convert (not to be confused with a converted trollop, I hasten to add). It also fits in rather nicely with the Victorian Literature Challenge and, although it is my fourth book towards the challenge, it is the first ‘traditional’ Victorian novel that I’ve read so far this year.

The eponymous Warden is Mr Septimus Harding, who presides over the twelve bedesmen of Hiram’s Hospital, a local almshouse. Everyone lives a comfortable, happy life until John Bold, a zealous young reformer who comes courting Mr Harding’s younger daughter, launches a campaign to redistribute the way that the income from the Hospital is apportioned between the bedesmen and the Warden as Bold believes the Warden receives an unfairly large amount. Soon the press are involved, Mr Harding’s good reputation is tarnished, the bedesmen become increasingly eager for more money and Mr Harding’s son in law Archdeacon Grantley is interfering. But the biggest problem of all turns out to be Mr Harding himself.

Ever since reading Elizabeth Goudge’s cathedral city books at the prompting of a wonderful English teacher I have been a fan of gentle stories of the clergy in which very little happens, so I was sold on the concept of The Warden before I even began to read it, and I wasn’t disappointed in the slightest. The story is sweet, charming and amusing, absorbing because of its characters and the way in which it is told rather than for what happens.

Ever since reading Elizabeth Goudge’s cathedral city books at the prompting of a wonderful English teacher I have been a fan of gentle stories of the clergy in which very little happens, so I was sold on the concept of The Warden before I even began to read it, and I wasn’t disappointed in the slightest. The story is sweet, charming and amusing, absorbing because of its characters and the way in which it is told rather than for what happens.

By far the most appealing aspect of the book is Trollope himself. His narratorial style is both distinctive and enjoyable. I love the way in which he alternates between protesting that he has no control over what happens to the characters as they act entirely of their own volition and assuring the reader not to worry about the characters because he knows exactly what will happen to them and it is nothing bad. His persona as the narrator come as being genial, jocular and slightly bumbling, like an elderly uncle in a Dickens novel (an impression not helped by his bearded and bespectacled physical appearance), but at the same time it is impossible to forget that as an author he is sharp and intelligent, capable of making keen observations and challenging accepted ideas even though the story itself is very mild. I enjoyed this so much that I think I’d gladly read him talking about almost anything if this is the style in which he does it. Thankfully I have lots more Trollope to discover as this impressively prolific author wrote forty-seven novels, as well as a handful of other works.

The Warden by Anthony Trollope, illustrated by Peter Reddick. Published by the Folio Society, 1976, pp. 234. Originally published in 1855.

Penguin Mini Modern Classics: Saki

Although I may have no resolve at all when faced with a second hand bookshop, usually I have a will of iron in the face of one selling new books which are far beyond my comfortable price range at the rate at which I consume them. However, all the reviews which popped up recently of the Penguin Mini Modern Classics, released to celebrate the 50th birthday of the Penguin Modern Classic, had piqued my interest. Although I gazed covetously at the complete box set on Amazon I decided that it would make more financial sense to buy a few of them to start out, and when I went into Waterstones to see them on 3 for 2 my mind was made up. I selected three lovely little books by authors whom I’ve never read before as a way of introducing myself to their writing. The first one I picked up to read was the offering from Saki, intriguingly entitled Filboid Studge, the Story of a Mouse That Helped, a collection of seven of his short stories: ‘Filboid Studge, the Story of a Mouse That Helped’, ‘Tobermory’, ‘Mrs Packletide’s Tiger’, ‘Sredni Vashtar’, ‘The Music on the Hill’, ‘The Recessional’ and ‘The Cobweb’.

Although I may have no resolve at all when faced with a second hand bookshop, usually I have a will of iron in the face of one selling new books which are far beyond my comfortable price range at the rate at which I consume them. However, all the reviews which popped up recently of the Penguin Mini Modern Classics, released to celebrate the 50th birthday of the Penguin Modern Classic, had piqued my interest. Although I gazed covetously at the complete box set on Amazon I decided that it would make more financial sense to buy a few of them to start out, and when I went into Waterstones to see them on 3 for 2 my mind was made up. I selected three lovely little books by authors whom I’ve never read before as a way of introducing myself to their writing. The first one I picked up to read was the offering from Saki, intriguingly entitled Filboid Studge, the Story of a Mouse That Helped, a collection of seven of his short stories: ‘Filboid Studge, the Story of a Mouse That Helped’, ‘Tobermory’, ‘Mrs Packletide’s Tiger’, ‘Sredni Vashtar’, ‘The Music on the Hill’, ‘The Recessional’ and ‘The Cobweb’.

Saki’s stories are absolutely marvellous. They remind me a bit of E. F. Benson in their tone and focus on the foibles of the upper middle class, but unlike Benson (who I always feel has a soft spot for his characters no matter how much he may mock them) Saki is merciless in his approach. The stories are dry, witty and biting and if they were long enough for the reader to get to know the characters at all it would be easy for them to seem rather cruel, but because they are only brief snapshots the reader is able to laugh without any accompanying feeling of guilt. They may be a little bizarre and dark at times (‘Sredni Vashtar’ for example is the story of a young boy who has a pet ferret that he turns into a god) but, unlike some of the more modern short stories that I’ve read, they always have a proper narrative arc and so they are very satisfying to read.

Although all the stories are entertaining, my two favourites are ‘Tobermory’ and ‘Mrs Packletide’s Tiger’. ‘Tobermory’ is about Mr Cornelius Appin, who announces at Lady Blemley’s weekend gathering that he has found a way to teach animals to talk and has successfully taught the cat, Tobermory, to talk. The guests however are less than impressed when it becomes apparent that Tobermory enjoys exercising his new linguistic talents to reveal all the secrets of the guests at the party to the assembled crowd:

An archangel ecstatically proclaiming the Millennium, and then finding that it clashed unpardonably with Henley and would have to be indefinitely postponed, could hardly have felt more crestfallen than Cornelius Appin at the reception of his wonderful achievement. (p. 17)

I think this comparison is just brilliant in its bathos. It conveys how ludicrous the guests’ objections are in the face of such an amazing discovery and how bound they are by social convention. It makes me chuckle every time I read it. Saki also gives Tobermory a wonderful voice and personality which conveys a sense of relish at embarrassing and shaming his listeners with the things they say and do behind closed doors. I only wish it had been a longer tale.

‘Mrs Packletide’s Tiger’ concerns a lady who decides that she wants to shoot a tiger in order to outdo Loona Bimberton who has just flown in a aircraft. Soon a suitable candidate is found:

Circumstances proved propitious. Mrs Packletide had offered a thousand rupees for the opportunity of shooting a tiger without overmuch risk or exertion, and it so happened that a neighbouring village could boast of being the favoured rendezvous of an animal of respectable antecedents, which had been driven by the increasing infirmities of age to abandon gamekilling and confine its appetite to the smaller domestic animals. The prospect of earning the thousand rupees had stimulated the sporting and commercial instinct of the villagers; children were posted night and day on the outskirts of the local jungle to head the tiger back in the unlikely event of his attempting to roam away to fresh hunting-grounds, and the cheaper kinds of goats were left about with elaborate carelessness to keep him satisfied with his present quarters. The one great anxiety was lest he should die of old age before the date appointed for the memsahib’s shoot. Mothers carrying their babies home through the jungle after the day’s work in the fields hushed their singing lest they might curtail the restful sleep of the venerable herd-robber. (p. 22)

It seems so ridiculous, and yet the task proves much trickier than Mrs Packletide anticipates with humorous results.

It seems that a lot of people have been reading Saki recently, and before writing my review today was treated to reviews from Simon of Stuck in Book, Lyn of I prefer Reading and Hayley of Desperate Reader who’ve all been reading Saki’s The Unbearable Bassington. After reading these, I’m now looking forward to reading more Saki even more than I was after reading this short story collection. What a lovely introduction!

Filboid Studge, the Story of a Mouse That Helped by Saki. Published by Penguin, 2011, pp. 66. Originally published in 1911 and 1914.

‘A Flower Wedding’ by Walter Crane

Since the Old English Thorn and I finally became engaged the summer before last I have acquired a small stack of wedding themed books. Most of it is of the fun and frothy, pastel covered, predictably plotted variety (which I’m actually rather looking forward to reading), but I have picked up a few more unusual wedding books. A Flower Wedding: Described by Two Wallflowers by Walter Crane falls into this latter category. I first became aware of Walter Crane’s artwork when I fell in love with the cover illustration for my copy of The Vet’s Daughter by Barbara Comyns and, on discovering the name of the artist, spent many happy hours browsing through his beautiful pictures on the internet. As a lot of Crane’s work is in fact illustration I decided that it would be nice to start collecting his books and A Flower Wedding seemed like an appropriate volume with which to start.

Since the Old English Thorn and I finally became engaged the summer before last I have acquired a small stack of wedding themed books. Most of it is of the fun and frothy, pastel covered, predictably plotted variety (which I’m actually rather looking forward to reading), but I have picked up a few more unusual wedding books. A Flower Wedding: Described by Two Wallflowers by Walter Crane falls into this latter category. I first became aware of Walter Crane’s artwork when I fell in love with the cover illustration for my copy of The Vet’s Daughter by Barbara Comyns and, on discovering the name of the artist, spent many happy hours browsing through his beautiful pictures on the internet. As a lot of Crane’s work is in fact illustration I decided that it would be nice to start collecting his books and A Flower Wedding seemed like an appropriate volume with which to start.

A Flower Wedding is an illustrated verse story describing the marriage of Lad’s Love and Miss Meadow Sweet and is essentially an excuse for Crane to mention the names of as many flowers as possible so that he can draw them all. It is a very short piece, each page featuring a single couplet or half couplet which provides a caption for the accompanying image, but it is perfectly wrought. Crane’s illustrations are stunning and his incorporation of all the different flowers, both into the poem and into the pictures, is skilfully done.

The edition of this book that I have is an absolutely beautiful object, and one of the best arguments in favour of printed books that I’ve had the pleasure of reading for some time. It is bound in soft cream cloth with designs embossed on the boards and spine in gold; the corners are pleasantly rounded; the paper inside is thick and creamy; the endpapers are bright and eyecatching; and there is a pretty ribbon to mark your place. It was produced by the V & A Museum to tie in with their new exhibition The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900 and I can certainly see why. This is a book that I’m very glad to own and will definitely be returning to to admire the illustrations regularly.

A Flower Wedding: Described by Two Wallflowers by Walter Crane. Published by V&A, 2011, pp. 40. Originally published in 1905

‘More English Fairy Tales’ by Joseph Jacobs

I’ve spoken before on this blog about how much I love folk tales and fairy stories and I think that what the Victorian collectors such as Andrew Lang, Jeremiah Curtin and Joseph Jacobs did is amazing. Every time I visit Cecil Sharp House in Camden I silently give thanks for all the work that Sharp did travelling and recording folk songs and traditions. Yes, they may have ridden rough-shod over issues of ethnicity and shamelessly sanitised the tales for consumption by their Victorian audiences (sex is conspicuous by its absence), but they helped to preserve a tradition of stories which might otherwise have died out completely. How often nowadays do we sit around and listen to people telling stories to one another? I know that outside of folk clubs and festivals its not something that I’ve done since childhood, and while it is a huge shame that this type of social interaction is so rare in modern society, I can only be grateful that the efforts of these men to collect and write down these stories means that they have not passed into obscurity along with the traditional method of their telling.

I’ve spoken before on this blog about how much I love folk tales and fairy stories and I think that what the Victorian collectors such as Andrew Lang, Jeremiah Curtin and Joseph Jacobs did is amazing. Every time I visit Cecil Sharp House in Camden I silently give thanks for all the work that Sharp did travelling and recording folk songs and traditions. Yes, they may have ridden rough-shod over issues of ethnicity and shamelessly sanitised the tales for consumption by their Victorian audiences (sex is conspicuous by its absence), but they helped to preserve a tradition of stories which might otherwise have died out completely. How often nowadays do we sit around and listen to people telling stories to one another? I know that outside of folk clubs and festivals its not something that I’ve done since childhood, and while it is a huge shame that this type of social interaction is so rare in modern society, I can only be grateful that the efforts of these men to collect and write down these stories means that they have not passed into obscurity along with the traditional method of their telling.

I was thrilled, then, to receive a free copy of Joseph Jacobs’ More English Fairy Tales, published recently by Pook Press, from the LibraryThing Early Reviewers programme. This book is a facsimile of the original 1894 edition of the text, complete with gorgeous illustrations from John D. Batten. It comprises an impressive eighty seven fairy tales, many of which are variations on better known versions of the stories, such as the many different versions of Cinderella which appear, and all of which are quite short in length. All in all, it is a lovely collection to read, whether as an adult or a child.

I found the selection of stories really interesting, particularly in instances where they followed a basic outline that was familiar but with some subtle differences. The story that we all know as ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ appears in this collection as the story of Scrapefoot the Fox, who undergoes similar ursine exploits culminating in his being summarily defenestrated by the irate Bears. It makes me curious as to how this character was transformed from a male fox into the little girl Goldilocks from the tale more familiar today (apparently by way of being an old woman and then a young girl called Silver-hair, according to the appendix). Likewise, the well known story of the Pied Piper is altered by moving the setting from Hamelyn to Newtown on the shores of the Solent. I thought this might perhaps have been a change made by Jacobs, appropriating a foreign tale for his book of English stories, as he does warn in his introduction that ‘I do not attribute much anthropological value to tales whose origin is probably foreign‘ (p. x). However, Jacobs’ enlightening ‘Notes and References’ section which closes the book reveals that the story aparently made its way over to England with no help from the author, prompting me to wonder once again how this change took place. I was also delighted to stumble across an early version of what has become one of my favourite folk songs in ‘The Golden Ball’. A girl is to be hung, but cries out to the hangman:

Stop, stop, I think I see my mother coming!

O mother, hast brought my golden ball

And come to set me free?

She then repeats this, protesting that her father has also come to save her. However, each time the response is negative:

I’ve neither brought thy golden ball

Nor come to set thee free,

But I have come to see thee hung

Upon this gallows-tree.

Eventually her sweetheart turns up at the final moment with the promised golden ball and saves her. I first heard this sung while sat in the garden of a pub in Warwick, and fans of the marvellous folk band Bellowhead will recognise this as the song ‘Prickle Eye Bush’, which you can see them performing in all their enthusiastic glory here (seriously, go and watch them). Although the song tells most of the story itself, it’s still really interesting to find out where it comes from and get a bit of background.

For every old favourite, there are also plenty of new tales. I particularly liked the Hobyahs and their exploits, a species of interfering fairy folk who were entirely new to me. The range of different tales and styles is particularly good over the eighty seven stories and I think this would keep the interest of any reader, whether they had a specific interest in the morphology of traditional stories or not. However, for me it is the appendix which makes this book so interesting. Here Jacobs explains where all the tales were gathered, any history behind them and how they differ from other know variations. He strikes the perfect balance between being a storyteller and being an academic folklorist.

For every old favourite, there are also plenty of new tales. I particularly liked the Hobyahs and their exploits, a species of interfering fairy folk who were entirely new to me. The range of different tales and styles is particularly good over the eighty seven stories and I think this would keep the interest of any reader, whether they had a specific interest in the morphology of traditional stories or not. However, for me it is the appendix which makes this book so interesting. Here Jacobs explains where all the tales were gathered, any history behind them and how they differ from other know variations. He strikes the perfect balance between being a storyteller and being an academic folklorist.

It is worth passing comment on the particular edition from Pook Press, as obviously the content of the book hasn’t changed since 1894. More English Fairy Tales has long since passed into the public domain and you can read the whole thing for free, including the illustrations, on Project Gutenburg and it is available in numerous different versions on Amazon, all of which are facsimiles of the same text and so will look exactly the same as this one. With that in mind, it’s a shame that Pook haven’t added anything of their own to the book to induce the book shopper to buy this particular version. It’s a perfectly pleasant little book, but an introduction either from an editor at the company or, even better, from someone who works in the field now or an author who writes modern fairy tales perhaps would have made it stand out a bit more. Pook state that they are ‘working to republish these classic works in affordable, high quality editions, using the original text and artwork so these works can delight another generation of children’ which is an aim that I find admirable, but I think just a few paragraphs explaining why this work is special, how it fits in with their catalogue and a bit of historical context would have been great.

More English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs, illustrated by John D. Batten. Published by Pook Press, 2011, pp. 243. Originally published in 1894.