Review: ‘The Mill on the Floss’ by George Eliot

There has been some discussion circulating around book blogs recently concerning abandoning books, and whether people prefer to persevere with reading in spite of not enjoying a book or to put it aside because life is too short to read things that aren’t appealing. I’ve spoken before about how I subscribe to what I term the Mastermind method of reading: I’ve started so I’ll finish. I don’t like to leave a book unfinished, partly because I’m an eternal optimist and continue hoping that a book might improve right till the bitter end, and partly because I often find even reading books I don’t enjoy can be a valuable experience, if only because it helps me to clarify what I don’t like. Sometimes however, books get started and then forgotten about, through no fault of their own or deliberate intention on my part. This has happened to my poor copy of George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss twice now, so I figured I owed it to the book to get to the end this time, come hell or high water. Abandon it a third time and it would no doubt start to develop a complex. The two accidental discardings of this book had somehow given me the unreasonable impression that it was going to be unduly difficult or tiresome, but I was determined to make it past the bookmark lodged ominously after page 139. It turns out that I needn’t have worried, as George Eliot’s writing is lovely, the characters are interesting and the story is engaging.

There has been some discussion circulating around book blogs recently concerning abandoning books, and whether people prefer to persevere with reading in spite of not enjoying a book or to put it aside because life is too short to read things that aren’t appealing. I’ve spoken before about how I subscribe to what I term the Mastermind method of reading: I’ve started so I’ll finish. I don’t like to leave a book unfinished, partly because I’m an eternal optimist and continue hoping that a book might improve right till the bitter end, and partly because I often find even reading books I don’t enjoy can be a valuable experience, if only because it helps me to clarify what I don’t like. Sometimes however, books get started and then forgotten about, through no fault of their own or deliberate intention on my part. This has happened to my poor copy of George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss twice now, so I figured I owed it to the book to get to the end this time, come hell or high water. Abandon it a third time and it would no doubt start to develop a complex. The two accidental discardings of this book had somehow given me the unreasonable impression that it was going to be unduly difficult or tiresome, but I was determined to make it past the bookmark lodged ominously after page 139. It turns out that I needn’t have worried, as George Eliot’s writing is lovely, the characters are interesting and the story is engaging.

Maggie Tulliver is an intelligent, impetuous little girl who lives in the Mill of the title. She plagues her mother with her unwillingness to behave in a neat, respectable way; she adores her straightforward but proud and litigious father; and she worships her older brother Tom, living for the times when he comes home from school. As she grows up, the Tulliver’s fall on hard times and she is forced into more subdued behaviour, although her passionate nature and readiness to love remain simmering beneath the surface. Slow and forthright Tom finds his place in his sister’s affections challenged by other men and Maggie faces difficult decisions.

Instead of focussing on romance as I expected, The Mill on the Floss is a book which explores relationships of all different kinds. It examines the ties that bind an extended family network of aunts, uncles and cousins together through thick and thin, so that the relatives who scold and tut and say “I told you so” can nonetheless always be relied upon to provide support and lend a helping hand where necessary. There are people drawn together out of pity, duty, friendship and tolerance. The romantic relationships depicted in the book vary widely in their nature, their causes and their means of expression; some arise out of kindness and mutual loneliness rather than love, while others are due to restlessness and adventure. Some relationships are easy and others are difficult and these are not always the ones that the reader might expect. And of course, there is never any doubt that the two most important men in Maggie’s life are her brother Tom and her father Mr Tulliver.

Maggie herself is a fascinating character. As a quick-witted, volatile little girl of violent passions she is utterly believeable. Her emotionally charged decisions to cut off her hair or to run away with the gypsies are shown as being perfectly logical through Maggie’s childliek reasoning, though her repentence following these irrevocable decisions is swift and easily anticipated by the reader. Her growth into a quieter, more mature and subdued figure is equally believeable, although it is not a little disappointing to see her spirit being crushed by circumstances. She is not the sort of character that is always likeable, but she is constantly fascinating and the reader genuinely wants her to find happiness.

The best aspect of the book, for me, was George Eliot’s prose which is always insightful and heartfelt. For example, when she talks about Tom returning home from a term away at school:

But it was worth purchasing, even at the heavy price of the Latin Grammar — the happiness of seeing the bright light in the parlour at home, as the gig passed noiselessly over the snow-covered bridge: the happiness of passing from the cold air into the warmth and the kisses and smiles of that familiar hearth, where the pattern of the rug and the grate and the fire-irons were ‘first ideas’ that it was no more possible to criticize than the solidity and extension of matter. There is no sense of ease like the ease we felt in those scenes where we were born, where objects become dear to us before we had known the labour of choice, and where the outer world seemed only an extension of our own personality: we accepted and loved it as we accepted our own sense of existence and our own limbs. Very commonplace, even ugly, that furniture of our early home might look if it were put up to auction; an improved taste in upholstery scorns it; and is not the striving after something better and better in our surroundings the grand characteristic that distinguishes man from the brute — or, to satisfy a scrupulous accuracy of definition, that distinguishes the British man from the foreign brute? But Heaven knows where that striving might lead us, if our affection had not a trick of twining round those old inferior things — if the loves and sanctities of our life had no deep immovable roots in memory.

Unfortunately, just as I keep reading books I don’t enjoy in the hope that they will improve, so a book can deteriorate as it progresses, and I found myself loving The Mill on the Floss right up until the ending, which I loathed. I’m desperately trying not to give anything away, but it is overly sentimental and completely out of keeping with the rest of the novel up to that point both in content and tone. I really wish that it had ended differently, but I remain pleased to have finally made it to the end of this book.

The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot. Published by Fontana, 1979, pp. 507. Originally published in 1860.

Commonplace Quotations

In recent times, muffins have regained some popularity; in common with crumpets and pikelets, they provide a physical base and a pretext for eating melted butter.

- The Pleasures of English Food by Alan Davidson

Review: ‘Death of a Naturalist’ by Seamus Heaney

Despite my resolution to read more poetry this year I don’t seem to have achieved that aim terribly well. Probably because I can’t read poetry on the train as I find poems tend to be too short for me not to become distracted by what’s going on around me. I also find that poetry requires a different type of concentration to a novel; a good novel absorbs me so that I forget where I am, but a good poem expects me to use my brain and engage with it in a different way. This is far more difficult to manage when surrounded by commuters at stupid o’clock in the morning. March’s TBR Lucky Dip provided a timely reminder that I should probably get back to the poetry books when it selected Seamus Heaney’s Death of a Naturalist for me to read a few months ago. I finished it at the beginning of April and now it’s finally getting its review, so my thoughts may be a little scattered to say the least.

Despite my resolution to read more poetry this year I don’t seem to have achieved that aim terribly well. Probably because I can’t read poetry on the train as I find poems tend to be too short for me not to become distracted by what’s going on around me. I also find that poetry requires a different type of concentration to a novel; a good novel absorbs me so that I forget where I am, but a good poem expects me to use my brain and engage with it in a different way. This is far more difficult to manage when surrounded by commuters at stupid o’clock in the morning. March’s TBR Lucky Dip provided a timely reminder that I should probably get back to the poetry books when it selected Seamus Heaney’s Death of a Naturalist for me to read a few months ago. I finished it at the beginning of April and now it’s finally getting its review, so my thoughts may be a little scattered to say the least.

Death of a Naturalist is a wonderful collection of poems which chiefly deal with Heaney’s rural Irish childhood and heritage. Individually, they are earthy and emotional and they combine together to form an impressive and coherent whole picture. What sets Heaney’s poetry apart is the sensuous quality of the language, how the words sound when said aloud and how they feel in the mouth. He seems to take great delight in rhyme, in onomatopoeia, in sibilant and plosive sounds and the physicality of words. This is definitely a collection which begs to be read aloud.

The poems themselves are a potent blend of nostalgia towards innocent childhood activities and a peculiar menace or sorrow. This becomes more pronounced as the book advances, ranging from the wild, childish imaginings of the titular poem ‘Death of a Naturalist’, in which Heaney pictures the frogs and frogspawn that so absorb his younger self fighting back:

The great slime kings

Were gathered there for vengeance and I knew

That if I dipped my hand the spawn would clutch it.

This becomes more explicit in poems such as ‘The Early Purges’, where he observes animals being killed:

Still, living displaces false sentiments

And now, when shrill pups are prodded to drown

I just shrug, ‘Bloody pups’. It makes sense:‘Prevention of cruelty’ talk cuts ice in town

Where they consider death unnatural

But on well-run farms pests have to be kept down.

And continues with the most heartbreaking line which finishes ‘Mid-term Break’, about the death of Heaney’s younger brother while he was away at school:

A four foot box, a foot for every year.

That’s not to say that Death of a Naturalist is all doom and gloom, but it is deeply felt and evocatively written all the way through.

Death of a Naturalist by Seamus Heaney. Published by Faber, 199, pp. 46. Originally published in 1966.

TBR Lucky Dip: June

As I explained in my post about reading plans for the new year, each month I’m going to be using a random number generator to select a book from my TBR pile for me to read, to help me read more widely from my shelves.

This month, the deities of www.random.org have ordained that I should read book number 147 . According to my TBR list this means that I am reading…

The Pleasures of English Food by Alan Davidson

Stargazey pie, Cheshire cheese, toffee apples, fish and chips, Sussex pond pudding, Cumberland sausages, pasties, gingerbread, dumplings, and Cox’s orange pippins are just some of the edible delights in this glorious celebration of English food from across the country and its history. From the etiquette of afternoon tea to the origins of mince pies, from the best way to eat a Stilton to how to cook a proper Yorkshire pudding, here are both well-loved favourites and unsung heroes from the nation’s mouth-watering culinary heritage.

This is another book from the English Journeys box set that I bought earlier this year. It’s not one I would have picked up just yet as I’m terrible at remembering to read things other than novels and memirs, so the TBR Lucky Dip has served its purpose admirably this time. Like the first book from the set that I attempted, Through England on a Side-Saddle by Miss Celia Fiennes, this sounds just my sort of book. Descriptions of traditional and local dishes and ingredients from all over England, combined with an investigation into their histories? Yes please! However, Miss Celia Fiennes was such a disappointment that I’m a bit nervous about approaching this one and I’m really hoping this one doesn’t go the same way.

Review: ‘The Circle Cast’ by Alex Epstein

Stories of King Arthur and the characters around him have been a large part of my reading diet for as long as I can remember. I’ve read classic retellings, obscure retellings and a desire to discover the early retellings is what led to me becoming an unemployable medieval English postgraduate. They’re stories that have become very close to my heart and I feel absurdly protective towards them, so I was excited and apprehensive in equal measures when I won a free review copy of The Circle Cast by Alex Epstein from the LibraryThing Early Reviewers programme, subtitled as it is ‘the lost years of Morgan le Faye’.

Stories of King Arthur and the characters around him have been a large part of my reading diet for as long as I can remember. I’ve read classic retellings, obscure retellings and a desire to discover the early retellings is what led to me becoming an unemployable medieval English postgraduate. They’re stories that have become very close to my heart and I feel absurdly protective towards them, so I was excited and apprehensive in equal measures when I won a free review copy of The Circle Cast by Alex Epstein from the LibraryThing Early Reviewers programme, subtitled as it is ‘the lost years of Morgan le Faye’.

The Circle Cast aims to fill in the gap between the time when Morgan is first seen as the daughter of Ygraine and Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall, and when she later reemerges as Arthur’s seductress and the mother of Mordred, his eventual downfall. How does a young girl who is sent into exile, either for her own protection or simply to keep her out of the way as Uter Pendragon begins a passionate relationship with her mother, become a powerful and vengeful sorceress?

Perhaps because Alex Epstein chooses to address Morgan le Fay’s childhood, an area of the legends which is not traditionally covered (in fact, only The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley springs to mind) and so is able to create entirely new material, I found this book rather enjoyable. It used a familiar setting and some familiar characters but it didn’t trespass on the traditional stories: it added to them instead and I found this a refreshing and interesting approach.

Morgan, or Anna as she begins the story, is a surprisingly complex character who develops convincingly throughout the course of the novel. She starts out curious, questioning and vulnerable but quickly acquires a steely resolve and an adult mindset as she is forced to mature by her circumstances. She’s so controlled and self-sufficient for much of the book that I don’t find her a particularly sympathetic character, but she’s still really interesting and a great strong female protagonist for a young adult story. I thought it was particularly poignant and a clever touch that what she works towards in Ireland, unification under one High King, is exactly what Arthur later works towards in Britain.

Of course, approaching such well known stories in any way, even Epstein’s rather oblique one, creates a set of problems for the author and reader. It can be difficult to create tension an excitement in a story where the reader already knows the ending, and I was well aware that the question posed on the back cover of the book, ‘But when Morgan meets the handsome son of a chieftain, will she choose love or vengeance?‘ was not really a question at all. Almost everyone reading this book will know that Morgan returns to Britain, seduces Arthur and gives birth to Mordred. The tension then has to come from the writer either making the reader forget that the conclusion of the novel is inevitable or making the choices that the characters have to make so agonising that the reader wishes there were some other option. Every time I go to see Blood Brothers I always find myself hoping against hope that this particular time it might end differently, despite all rational thought meaning I know it can’t, so I know that this can be achieved. in The Circle Cast Epstein manages it as well, by and large, and even though I knew what Morgan would decide her situation was compelling enough that I caught myself wishing that this wasn’t the case.

I also liked the way that, although the reader was never allowed to forget the connection to the Arthurian story, Epstein worked in other stories subsidiary to Morgan’s which provide context. I particularly liked the story of Luan who wanted to live a Christian life of prayer rather than the life of a chieftain’s daughter. The way in which she dealt with achieving her aims in a male dominated society provided a contrasting counterpoint to Morgan’s situation which added richness to the story.

However, in spite of my enjoyment of Morgan’s story I have two problems with this book, the first zoological and the second temporal. They may be relatively minor quibbles but both of them jolted me out of the narrative rather an immersing me further in the story. Problem number one then. There are two rather strange wildlife appearances in the novel. The first is when Anna is travelling by boat across the Irish Sea from Cornwall to Ireland and the following description cropped up:

When Morgan woke they were sailing through a vast flock of pelicans, thousands of them floating on the water, hundreds more reeling above their heads. One of them dove at the water and came up with a fish. (p. 58

Now, to the best of my knowledge, there are no pelicans in the Irish Sea, nor have there ever been. Puffins, yes. Seagulls, yes. Pelicans, no. A quick Google suggests that they don’t come any closer to the British Isles than the extreme south east of Europe. The other issue was equine, when Morgan discovers a three-toed horse, which she takes as a special creature. Once again, the best of my knowledge is largely represented by Wikipedia and consultation with some horsey friends, but nevertheless sources seem to agree that equus has one toeand the mesohippus shown on this diagram with three toes horses died out around 40 million years ago, which is a little old for Morgan to be riding one. I am of course not an expert on historical zoology and this isn’t to say that I’m not wrong; Google, after all, is not infallible. However, even if these animals are technically correct, they don’t feel as though they fit within the locale and time period that Epstein is evoking and so they would have been better substituted for more typical wildlife which instantly suggests Dark Age Britain. Edit: Apparently I’m wrong about the horses. They do occasionally come about as a genetic throwback, and Julius Caesar’s horse Beaucephalus had three toes. Knowing this, it actually makes Morgan’s three toed mount a rather clever idea rather than a slightly peculiar one, as it places her in a context of great leaders. Thanks to the author for clearing that one up.

My other problem with the book was the inconsistent timescale: the amount of time that Morgan spends in slavery seems to vary hugely. When she escapes to join the Christian community, we are told that ‘Morgan tucked into her first proper meal in eight years‘ (p. 142); later she rescues the Greek slave who came to Ireland with her from Cornwall and ‘she could see he was trying to turn the twelve-year-old he had lost into the sixteen-year-old in the white cloth and gold that stood before him’ (p. 240); later still she meets the man who enslaved her and ‘The head on the grass was ten years older’ (p. 244). Even a brief glance shows that these timings don’t match up, and I wish that some more careful editing had picked this up so that it could be fixed.

With these two exceptions I really enjoyed this novel. I like Alex Epstein’s writing and I get the feeling that we’d get on rather well if we ever met, and would spend hours geeking out over Arthurian legend. I hope he continues to write more stories in this vein, perhaps continuing with Morgan’s tale, as I’d really like to read them.

The Circle Cast by Alex Epstein. Published by Tradewinds, 2010, pp. 300. Originally published in 2010.

Review: ‘Dawn Chorus’ by Joan Wyndham

Reading Perfume from Provence reminded me that reading non-fiction is nowhere near as hard or as serious as I think it’s going to be when it comes in the form of an engaging memoir. I decided to carry on the theme by reading another thoroughly English memoir which I picked up, this time one of upper class childhood, Dawn Chorus by Joan Wyndham. It starts with the incredibly tantalising paragraph :

Reading Perfume from Provence reminded me that reading non-fiction is nowhere near as hard or as serious as I think it’s going to be when it comes in the form of an engaging memoir. I decided to carry on the theme by reading another thoroughly English memoir which I picked up, this time one of upper class childhood, Dawn Chorus by Joan Wyndham. It starts with the incredibly tantalising paragraph :

The first three years of my childhood were spent in a vast Victorian country house in Wiltshire called Clouds. Built entirely of green sandstone, it boasted forty bedrooms, and a kitchen so far from the dining room that a miniature railway track had to be built to carry food from one place to the other. Luckily, tepid meals were the norm in those days.

How could I possibly resist such an opening?

In Dawn Chorus Joan Wyndham tells the story of her family, beginning with her great-grandfather, Percy, who built Clouds to be his family home and continuing on through the generations down to her own memories of her childhood and teenage years. Her life begins in 1921 at the second incarnation of Clouds, the first having burned down before she was born, then is transported to London after her parents separate, where her mother’s friends, a group known as ‘the Souls’ simultaneously entertain and embarrass her with their eccentric antics. Joan attends a convent school and has a somewhat tempestuous relationship both with religion and the nuns responsible for her education, until she goes to the theatre and sees John Gielgud as Hamlet, whereupon she decides to audition for RADA.

This is a wonderful memoir, not only because the subject matter than it chronicles is so interesting, but also because the evidence on which Joan Wyndham draws is so miraculously complete. Her relatives seem to have been meticulous record keepers, and so her accounts of their history is littered with diary entries and excerpts from letters which lend a great immediacy to the writing. Her own letters and diaries are written with remarkable candour and shared with an openness and lack of embarrassment which makes Dawn Chorus a delight to read. Even though I do not doubt that the selections used have been carefully chosen, Wyndham seems quite happy to display her younger self both at her best and at her worst. I cannot think of many writers who would share their awkward teenage diaries, rife with overblown emotions and incidents rather forgotten, so willingly with the reading public.

Whatever subject she is talking about, Joan’s diary entries are warm and filled with emotion so that she really leaps off the page and comes to life. They are often highly amusing, although sometimes not intentionally so, imbued as they are with the seriousness of youth. At one point, she goes to stay with a family in Paris:

Friday For three days now there has been no paper in the Tante Fannee. I’ve had to use all the tissue paper from my trunk. Luckily, I have been asked to dinner by my Romanian relatives in Paris. They are very grand and rich so I will probably be able to pinch a few rolls of paper to take home with me.

On another occasion, Joan goes on holiday to Wales:

I have become the complete ‘hearty’ down here, striding out in the dew before breakfast in corduroy trousers with a stick, a whistle and two dogs, and then down to the farm to feed the cows and see the newborn calf. Then back for a breakfast of kidneys, bacon and pickled herring, followed by a few rounds of clock golf, finally taking the rowing-boat out for a cruise around the outlying islands, with binoculars slung round my neck, and no makeup. Horrible metamorphosis!

On a more genteel note, we also sold produce at the Vicar’s bazaar, raffled teasets at the Conservative fete and made conversation over tomato sandwiches at various county tea parties. I’ve also been climbing the mountains around Snowdon. So bleak that nothing grows on them but the sparsest grass, with thin streams running down into the hidden lakes, and sheep lying curled in the rock crevices. One of the lakes is supposed to be bottomless but I fell into it, so I can positively state that it isn’t; it’s shadowed by red-berried mountain ash. Mountains almost reconcile one to Wordsworth.

There is a similar brutal and entertaining honesty in the extracts from her family’s writing that she includes. Take, for example, her mother’s record of Joan’s early development in her Baby’s Progress Book:

Joan is never still for one moment and exhausts all who look after her. When finally tired out, she sits and twiddles her hair without ceasing.

Hearing Hears more than is good for her.

Smell Good, but has a habit of snorting.

Sight Slight squint.

Taste Greedy

Later on there is no doubt at all of the genuine affection between Joan and her mother, as evidenced by their numerous letters to one another, but her mother’s evident frustration with her young baby and the ruthless way in which she records it is highly entertaining.

This book can become a bit confusing at times, as Joan tends to refer to people by their first names rather than their relationship to her, so it can become easy to lose track of who is who and in which generation. Nevertheless, this is a fine memoir of life in England for the upper classes between the Wars, and definitely one that should be more widely known (according to LibraryThing only two other people own a copy of this book, so the vast majority are missing out). Joan Wyndham continued to chronicle her life in several other books, and I enjoyed her style so much that I’m sure it won’t be long before they find their way onto my shelves.

Dawn Chorus by Joan Wyndham. Published by Virago, 2004, pp. 233. Originally published in 2004.

Virago Book Club Event: Winifred Holtby

Last Thursday evening saw the second gathering of the Virago Book Club to discuss the second book selection, Winifred Holtby’s masterpiece South Riding. I instantly fell in love with the book when I read it back in January so I was looking forward to an evening of discussion with a group of people who all, it transpired (and not exactly unexpectedly), felt the same way about it. Perhaps it was because it was a smaller gathering than the previous event with Linda Grant and obviously there was no author there to give a talk, or perhaps it was because we’re all a bit more familiar with each other having met before, but there was lots of friendly chatter, lively discussion and enthusiastic praise of South Riding as well as of Winifred Holtby herself. Combine that with a delicious chocolate cake and some wine and a lovely evening was had by all.

Last Thursday evening saw the second gathering of the Virago Book Club to discuss the second book selection, Winifred Holtby’s masterpiece South Riding. I instantly fell in love with the book when I read it back in January so I was looking forward to an evening of discussion with a group of people who all, it transpired (and not exactly unexpectedly), felt the same way about it. Perhaps it was because it was a smaller gathering than the previous event with Linda Grant and obviously there was no author there to give a talk, or perhaps it was because we’re all a bit more familiar with each other having met before, but there was lots of friendly chatter, lively discussion and enthusiastic praise of South Riding as well as of Winifred Holtby herself. Combine that with a delicious chocolate cake and some wine and a lovely evening was had by all.

The evening began with a discussion about the two editions of the book currently available: the lovely new Virago edition, the cover of which is from an old Yorkshire railway poster, and the television tie-in edition which is published by another company. We were all rather surprised to learn that the BBC edition wasn’t from Virago, but apparently since Winifred Holtby has been dead for more than seventy years, South Riding is now in the public domain and can therefore be published by anyone. However, Vera Brittain’s estate gave Virago permission to use an afterward that she wrote which hasn’t been published since the 1930′s (if my memory serves me correctly) and their version also features an introduction by Shirley Williams, Vera Brittain’s daughter, so it’s worth choosing this edition for the extra material alone, not to mention the vastly superior cover. We all agreed that we prefer not to buy television tie-in editions with actors on the cover as we prefer to imagine the characters ourselves rather than to have a preconceived idea of what they look like before we begin to read.

The evening began with a discussion about the two editions of the book currently available: the lovely new Virago edition, the cover of which is from an old Yorkshire railway poster, and the television tie-in edition which is published by another company. We were all rather surprised to learn that the BBC edition wasn’t from Virago, but apparently since Winifred Holtby has been dead for more than seventy years, South Riding is now in the public domain and can therefore be published by anyone. However, Vera Brittain’s estate gave Virago permission to use an afterward that she wrote which hasn’t been published since the 1930′s (if my memory serves me correctly) and their version also features an introduction by Shirley Williams, Vera Brittain’s daughter, so it’s worth choosing this edition for the extra material alone, not to mention the vastly superior cover. We all agreed that we prefer not to buy television tie-in editions with actors on the cover as we prefer to imagine the characters ourselves rather than to have a preconceived idea of what they look like before we begin to read.

Interestingly (and unusually) I seemed to be the only person there who had watched the recent BBC adaptation of South Riding. I had enjoyed it for what it was, but it wasn’t a patch on the book because it had to take a much more narrow focus than the novel, essentially turning it into a love story with a bit of social reform thrown in. I think that this is partly because of the time constraints of adapting such a wide-reaching novel into three hour long segments and partly because I just don’t think it would have worked on the screen. As we discussed, one of the most impressive things about this book is that Winifred Holtby takes so many different characters from a huge range of backgrounds and professions and makes them all individuals that the reader knows personally and who have fascinating stories to tell. To have so many characters in a television programme would just have been confusing, rather than providing the amazing cross-section of society that it does in the book.

We chatted a bit about how we had all come to read the book; some people had read it when they were younger and then read it again for the Book Club, but the majority of us had only discovered it because of the Book Club and so were suitably grateful! People tried to come up with a book that we would say that South Riding is most like in order to describe it to other people who haven’t yet heard of it. Middlemarch of course was mentioned (making me all the more eager to get round to reading it myself) and also the Rabbit books by John Updike which I’ve not investigated before. I wish I’d noted them down at the time, because anything that purports to be like South Riding (and indeed, anything recommended by the lovely people at the meeting) has to be worth reading.

We also discussed Winifred Holtby’s relationships with the two incredibly strong and influential women in her life: her mother and Vera Brittain. We were read some extracts from a biography of Winifred Holtby called The Clear Stream by Marion Shaw which sounds fascinating and is now lurking in my Amazon shopping basket waiting for me to feel justified in buying books again to click and purchase, as it’s apparently no longer in print and is quite pricey second hand. Both were clearly women that Winifred respected, almost to the point of denying her own talents in deference to theirs; there was a particularly interesting exceprt from a letter than Winifred wrote to Vera saying that the fact that Winifred had been asked to write a biography of Virginia Woolf was obviously a reflection on her friendship with Vera rather than on her own personal merits as an author and journalist. It’s no wonder that she was like this given her mother, who seems to have been a formidable character who liked to be in control of her daughter. We’re all very thankful that Winifred Holtby ignored her mother’s displeasure to write South Riding and that Vera Brittain ensured that it was published.

We also discussed Winifred Holtby’s relationships with the two incredibly strong and influential women in her life: her mother and Vera Brittain. We were read some extracts from a biography of Winifred Holtby called The Clear Stream by Marion Shaw which sounds fascinating and is now lurking in my Amazon shopping basket waiting for me to feel justified in buying books again to click and purchase, as it’s apparently no longer in print and is quite pricey second hand. Both were clearly women that Winifred respected, almost to the point of denying her own talents in deference to theirs; there was a particularly interesting exceprt from a letter than Winifred wrote to Vera saying that the fact that Winifred had been asked to write a biography of Virginia Woolf was obviously a reflection on her friendship with Vera rather than on her own personal merits as an author and journalist. It’s no wonder that she was like this given her mother, who seems to have been a formidable character who liked to be in control of her daughter. We’re all very thankful that Winifred Holtby ignored her mother’s displeasure to write South Riding and that Vera Brittain ensured that it was published.

I left having had a wonderful evening, clutching a copy of the new Virago reissue of Anderby Wold, Winifred Holtby’s first novel. I started it on the train home and have now devoured it completely, so thank you to Virago for organising another lovely event and for introducing me to such a great author.

Review: ‘Perfume from Provence’ by Lady Winifred Fortescue

You might remember my mentioning Perfume from Provence by Lady Winifred Fortescue back in my March Review when I confessed to having broken my Lent book buying ban due to an unexpected train delay. Whilst I felt a little bit guilty at the time (not least because I also picked up the two companion books by the same author which wasn’t strictly speaking necessary) having finished the book I can safely say that never have I been more glad of the wrong kind of leaves on the line. Usually they are the bane of my existence, but in this case they led to me acquiring one of the warmest, sweetest, most delightful books that I have had the pleasure of reading this year. Any qualms I have have felt about picking up the other two books by this author, Sunset House and There’s Rosemary…There’s Rue, have vanished completely as I am certain that I’ll be wanting to read more from Lady Winifred soon.

You might remember my mentioning Perfume from Provence by Lady Winifred Fortescue back in my March Review when I confessed to having broken my Lent book buying ban due to an unexpected train delay. Whilst I felt a little bit guilty at the time (not least because I also picked up the two companion books by the same author which wasn’t strictly speaking necessary) having finished the book I can safely say that never have I been more glad of the wrong kind of leaves on the line. Usually they are the bane of my existence, but in this case they led to me acquiring one of the warmest, sweetest, most delightful books that I have had the pleasure of reading this year. Any qualms I have have felt about picking up the other two books by this author, Sunset House and There’s Rosemary…There’s Rue, have vanished completely as I am certain that I’ll be wanting to read more from Lady Winifred soon.

In this book, Lady Winifred writes about her experiences of moving to a tiny mountain village in Provence with her husband, referred to throughout as Monsieur, and the trials and tribulations of dealing with a new country. Not only does she come up against the barrier of language, both French and Italian, but also the completely different culture and way of life there. Her collection of amusing anecdotes about managing the builders, servants and gardeners, dealing with local officials, encountering the dubious honour of being invited to a wedding, and learning to drive on the treacherous mountain roads are all told with a smile, and ability to laugh at herself and a genuine love for the place that is utterly infectious. The illustrations by E. H. Shepherd which accompany the text throughout just make this book even more enjoyable to read. If I hadn’t wanted to visit Provence before, I certainly would after reading Perfume from Provence; as it is, I’m only more keen to go there someday.

The section on driving was particularly entertaining, not least because of the way in which Lady Winifred anthropomorphises her cars. There is the gallant English Sir William whom she has had to leave behind and her new little Fiat named Desiree because there is a long period of waiting for the car to arrive from the manufacturers during which she is ‘desiree mais pas trouve‘. But it is the section on driving lessons which is most endearing. My woes at the hands of the DVLA pale into comparison beside a friendly local teaching Winifred to brave the mountain roads by directing her up a precarious, winding track, completely unprotected from a long drop into the valley below on one side, which turns out to be a one way street running in the opposite direction to that in which she is driving. Of course, she only learns this on meeting a rather surprised car coming straight towards her. I also loved the account of how one of Winifred’s friends accidentally runs over her garden while Winifred is giving her a lesson and all the servants are enlisted to try to disguise the damage before the gardener notices, after which they gleefully conspire to deny all knowledge of noticing anything happening.

The section on driving was particularly entertaining, not least because of the way in which Lady Winifred anthropomorphises her cars. There is the gallant English Sir William whom she has had to leave behind and her new little Fiat named Desiree because there is a long period of waiting for the car to arrive from the manufacturers during which she is ‘desiree mais pas trouve‘. But it is the section on driving lessons which is most endearing. My woes at the hands of the DVLA pale into comparison beside a friendly local teaching Winifred to brave the mountain roads by directing her up a precarious, winding track, completely unprotected from a long drop into the valley below on one side, which turns out to be a one way street running in the opposite direction to that in which she is driving. Of course, she only learns this on meeting a rather surprised car coming straight towards her. I also loved the account of how one of Winifred’s friends accidentally runs over her garden while Winifred is giving her a lesson and all the servants are enlisted to try to disguise the damage before the gardener notices, after which they gleefully conspire to deny all knowledge of noticing anything happening.

Perfume from Provence is such a happy book, full of laughter and fond nostalgia, and I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend this relaxing, amusing tale of French rural life as seen through the eyes of the bemused but affectionate English to anyone at all.

Perfume from Provence by Lady Winifred Fortescue. Published by William Blackwood and Sons, 1947, pp. 274. Originally published in 1935.

May Summary

Another month gone by already and still I’m not caught up with my review backlog. I am, however, much closer to being up to date than I was this time last month, so perhaps June will be the month that I finally get there.

Another month gone by already and still I’m not caught up with my review backlog. I am, however, much closer to being up to date than I was this time last month, so perhaps June will be the month that I finally get there.

May has been yet another very busy month in the non-reading world, and June looks as though it’s going to be equally packed. This month’s exciting news is that the Old English Thorn and I have put down a holding deposit on our first rented flat together! With no particular requirements other than a decent commuting time from London it took us a while to settle on a location that we really liked, but this month we went to visit a lovely little town in Sussex and the very same day found the perfect flat. A morning off work later in the week and another trip back there made it ours and we’re both really happy. It even has a second bedroom that (naturally) is going to be a library. The landlords want to refurbish it after the previous tenants vacate (how terrible for us!) but it should be ours by mid July, although I won’t move in until after the September wedding. Speaking of the wedding, I’ve also just heard that our flowers are now all sorted, so things are moving along apace.

And now back to more bookish concerns. In May I read fewer books than usual, totalling fewer pages as well, which is an indication of how busy I’ve been. I managed 13 books this month, comprising 3,480 pages in total, making each book an average of 268 pages long. However, unlike in previous months when I’ve found reading shorter books a bit unsatisfying, in May it was exactly what I needed: nearly all of the books that I read were enjoyable and some are among my favourites for the year so far. Unusually for me, I’ve done quite a bit of rereading this month, three out of the thirteen books (marked with an asterisk) being ones that I’ve read and enjoyed before. This month I read:

- The Prince of Mist by Carlos Ruiz Zafon

- Wild Swans by Jung Chang

- Ballet for Drina by Jean Estoril*

- Elizabeth and her German Garden by Elizabeth von Arnim

- Song of Sorcery by Elizabeth Scarborough

- Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson

- Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen

- Drina’s Dancing Year by Jean Estoril*

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen*

- The House in Dormer Forest by Mary Webb

- The Sack of Bath by Adam Fergusson

- My Dirty Little Book of Stolen Time by Liz Jensen

I’ve had three stand out books in May. Pride and Prejudice was the next book on the pile for my rereads of Jane Austen and a guaranteed winner as I already knew I loved it. In fact, it was even better than I remembered and I enjoyed it even more than before, if that’s possible. Wild Swans by Jung Chang was also one that I expected to find interesting and it didn’t disappoint. The story of three generations of women growing up in China, from the author’s grandmother in the days of emperors and warlords to her own experiences during the Cultural Revolution, was absolutely fascinating and made the historical events of which I was vaguely aware seem real and personal. I cannot recommend this enough if you haven’t read it already. The surprise of the month came in the form of Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson. I had no particular expectations of this book, but the way in which the author played with fairytale tropes and with language just clicked with me, making it another five star read. I also particularly enjoyed Elizabeth and her German Garden by Elizabeth von Arnim (a good thing considering how many of her other books I have awaiting my attention) and My Dirty Little Book of Stolen Time by Liz Jensen.

This month’s dud was yet again a Virago title, I’m sorry to report. The House in Dormer Forest by Mary Webb, my lucky dip book for this month, proved to be absolutely atrocious. Thankfully it was terrible to the point of being amusing, so I at least had some enjoyment out of it, even if it was a very long way from what Mary Webb intended.

May saw the start of a fresh influx of books following the end of Lent’s (mostly successful) book buying ban. The first book I ordered was My Dirty Little Book of Stolen Time by Liz Jensen, which I’ve already read and really enjoyed. The remainder of my order from AwesomeBooks arrived, providing me with seven new Viragos to add to the teetering stack in my room: The Wind Changes by Olivia Manning, My Next Bride by Kay Boyle, Olivia by Dorothy Strachey, Rumour of Heaven by Beatrix Lehmann, She Knew She Was Right by Ivy Litvinov, Phoenix Fled by Attia Hossain and Never No More by Maura Laverty. Virago books were also very much the order of the day when I visited the Oxfam bookshop in Richmond while waiting for a train. I ducked in to avoid the rain and somehow emerged with The Matriarch by G.B. Stern, Delta Wedding by Eudora Welty and The Persimmon Tree by Marjorie Barnard. They all sound really interesting so I feel spoilt for choice!

My two rereads besides the Jane Austen were books that I bought this month from Amazon and then read immediately: Ballet for Drina and Drina’s Dancing Year by Jean Estoril. These are books that I used to own prior to the disaster with the leaking shed, and throwing away all my damp and mouldy old copies had made me nostalgic to read some of them again. This is a series that I’m going to continue to collect and read for when I need some simple, pleasant light relief. Another book which I bought and read instantly was The Prince of Mist by Carlos Ruiz Zafon. Reviews of these will follow eventually, I promise.

I’ve picked up some more books to add to my selection pool for the Victorian Literature Challenge. I managed to complete my Folio Society Barchester set by picking up the final three books in the series from Ebay, meaning I now have Framley Parsonage, The Small House at Allington and The Last Chronicles of Barset waiting for me when I finish those I already have. I also couldn’t resist a copy of East Lynne by Mrs Henry Wood in an Odhams edition which matches my Dickens set, particularly as she’s a new author, helpful for my additional aim to read all fifteen challenge books by different writers.

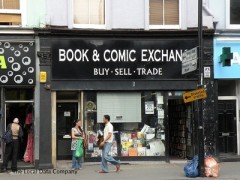

This month I paid my first visit (but definitely not my last) to the Notting Hill Book and Comic Exchange, much loved among bloggers. It’s a bit of a jumble sale and probably somewhere to go only when you have plenty of time for browsing through the rather haphazardly arranged books rather than on your lunch hour as I did. Still, I went with a large bag of books to get dispose of and came out with a considerably lighter, less stuffed bag containing nine exciting books as it was considerably more lucrative to take book vouchers in exchange for my unwanted books than cash. I was pleased to come across a selection of Virago Modern Classics down in their bargain basement where all books are £1. Thankfully for the groaning TBR pile, I already had most of them, but I still managed to come away with four: The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy, A View of the Harbour by Elizabeth Taylor and The Land of Spices and That Lady, both by Kate O’Brien. I also picked up two other Virago books that aren’t in the Modern Classics series: Life Before Man by Margaret Atwood (one of those authors I seem to be more interested in collecting than actually reading; I must rectify this next month) and The Paris Wife by Paula McClain in the gorgeous hardback ARC edition I’ve seen floating around on various blogs. My remaining purchases were The Burning Stone by Kate Elliot, part of a fantasy series I want to start soon, Daisy Fay and the Miracle Man by Fannie Flagg of Fried Green Tomatoes fame, and a curious looking little hardback book entitled Jocasta and the Famished Cat by Anatole France. Although it has a dust jacket there’s no indication of what the book is about, but I was so intrigued by the name that I had to take it home with me to find out!

This month I paid my first visit (but definitely not my last) to the Notting Hill Book and Comic Exchange, much loved among bloggers. It’s a bit of a jumble sale and probably somewhere to go only when you have plenty of time for browsing through the rather haphazardly arranged books rather than on your lunch hour as I did. Still, I went with a large bag of books to get dispose of and came out with a considerably lighter, less stuffed bag containing nine exciting books as it was considerably more lucrative to take book vouchers in exchange for my unwanted books than cash. I was pleased to come across a selection of Virago Modern Classics down in their bargain basement where all books are £1. Thankfully for the groaning TBR pile, I already had most of them, but I still managed to come away with four: The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy, A View of the Harbour by Elizabeth Taylor and The Land of Spices and That Lady, both by Kate O’Brien. I also picked up two other Virago books that aren’t in the Modern Classics series: Life Before Man by Margaret Atwood (one of those authors I seem to be more interested in collecting than actually reading; I must rectify this next month) and The Paris Wife by Paula McClain in the gorgeous hardback ARC edition I’ve seen floating around on various blogs. My remaining purchases were The Burning Stone by Kate Elliot, part of a fantasy series I want to start soon, Daisy Fay and the Miracle Man by Fannie Flagg of Fried Green Tomatoes fame, and a curious looking little hardback book entitled Jocasta and the Famished Cat by Anatole France. Although it has a dust jacket there’s no indication of what the book is about, but I was so intrigued by the name that I had to take it home with me to find out!

I also did a bit of book shopping when I had the pleasure of meeting some friends from LibraryThing in person. I was only able to go along and join their outing at lunchtime, which rather fortuitously coincided with their visit to the Persephone book shop. Of course, it’s impossible to come out of that shop with fewer than three books, and after much initial narrowing down of titles through browsing the website I plumped for Family Roundabout by Richmal Crompton, Cheerful Weather for the Wedding by Julia Strachey and Miss Buncle Married by D.E. Stevenson, which I’ve been looking forward to reading ever since I read Miss Buncle’s Book in February. There was just time for a quick visit to Lamb’s Bookshop further down the street, where I picked up The Fire Gospel by Michael Faber, one of the Canongate Myths books, before I had to head back to my office. It was lovely to put some faces to names and have a quick, bookish chat, not to mention it makes my book acquisition feel far less unreasonable when shopping with people buying just as many books as I am, if not more! I hope it’s an experience that will be repeated soon.

So, which of these books should I attack first? Have you read anything particularly good in May that I should add to my list for next month?

Review: ‘Nicholas Nickleby’ by Charles Dickens

Think of Victorian novels and which one author leaps immediately to mind? For me, and I suspect for many others, it is Charles Dickens. When taking part in a reading challenge which relates to Victorian literature, it seems only right to read something by the great man of Victorian literature himself. However, I have a confession to make (please don’t hurt me): Dickens has never particularly appealed to me. Up until now, my Dickens reading experience has been limited to books I have studied (the sum total of which consists of Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol and Great Expectations) but this has never stopped me enjoying books in the past so I can hardly blame that for my lack on enthusiasm. Nonetheless, with a handsome sixteen volume 1930′s complete Dickens set which I picked up in a charity shop staring accusingly down at me from the classics shelf I finally decided to just get on with it and pick up a volume. The one that I chose was Nicholas Nickleby.

Think of Victorian novels and which one author leaps immediately to mind? For me, and I suspect for many others, it is Charles Dickens. When taking part in a reading challenge which relates to Victorian literature, it seems only right to read something by the great man of Victorian literature himself. However, I have a confession to make (please don’t hurt me): Dickens has never particularly appealed to me. Up until now, my Dickens reading experience has been limited to books I have studied (the sum total of which consists of Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol and Great Expectations) but this has never stopped me enjoying books in the past so I can hardly blame that for my lack on enthusiasm. Nonetheless, with a handsome sixteen volume 1930′s complete Dickens set which I picked up in a charity shop staring accusingly down at me from the classics shelf I finally decided to just get on with it and pick up a volume. The one that I chose was Nicholas Nickleby.

The eponymous Nicholas Nickleby travels to London with his mother and sister, Kate, following the death of his father which leaves his family penniless. There he seeks help from their only remaining relative, Ralph Nickleby, who has no desire to assist Nicholas at all, and quickly packs him off to Yorkshire to take a low-paying job as assistant to the wicked school master Wackford Squeers. After witnessing the cruelty that goes on at Dotheboys Hall, Nicholas finds himself unable to stop himself intervening as Squeers punishes a particularly wretched boy known as Smike and is forced to flee back to London following his actions. THere he must once again find work to support his family, while defending his sister from the lecherous advances of Sir Mulberry Hawk and attempting to trace a mysterious lady he has seen.

There is much to be enjoyed in Nicholas Nickleby. The plot is engaging and its episodic structure, a legacy of publication in installments no doubt, causes it to tear along at an impressive pace, surprising considering the size (not to mention the tiny print) of the volume. The tone of the writing is often light and comic and it is populated by a whole host of entertaining caricatures, by turns repulsive and delightful, with equally entertaining names. Who could fail to be intrigued by such intriguing, and indeed revealing, names as Smike, Newman Noggs, Madame Mantalini, Sir Mulberry Hawk, Lord Frederick Verisopht, the brothers Cheeryble and of course, Wackford Squeers?

The problem with Nicholas Nickleby is that, even with my limited experience of Dickens, I was able to guess exactly what would happen to every last character the moment that they were introduced. This of course is not a problem in and of itself: there are plenty of authors whose books I love who are equally predictable. So often in literature it is not where and author goes with a book but the way in which they get there that is of interest, and this is something that I didn’t find wholly satisfying with Nicholas Nickleby. Dickens is by no means a concise writer and is often unnecessarily verbose, particularly when he was grinding the axe of social injustice. I know that he writes social satire and that his novels were intended to bring the plight of the urban poor to the attention of the masses, but as a reader I think they detract from the story with their length and sentimentalism.

I also found that, much as I enjoy Dickens’ well-written and insightful caricatures, I missed the presence of more developed and believable characters in the novel. This was particularly apparent with the young female characters, Kate Nickleby and Madeline Bray. They seem to have no function other than to be good, beautiful and submissive and act as lures for the evil gentlemen and ultimate rewards for their good counterparts. The two are so similar that they are virtually interchangeable, and I wish that they had at least a few distinguishing features and character traits. From the amount of times I’ve heard Little Dorrit referred to as ‘Little Doormat’ it would seem that this might be a problem which extends beyond Nicholas Nickleby into Dickens’ other works. I really hope that isn’t the case.

Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens. Published by Odhams, 1930, pp. 764. Originally published in serial, 1838-1839.