‘April Lady’ by Georgette Heyer

Oh, Georgette Heyer, how I wanted to like you! How I wanted to find your writing delightful, engaging and witty and your stories compelling and absorbing. How I looked forward to returning to the world of Jane Austen’s novels through such a prolific author that I could stay in that world for months of reading without ever having to be disturbed by more modern times and writing. How disappointed I was, then, when I finished April Lady and found that it was none of the things that I had been anticipating so eagerly.

Oh, Georgette Heyer, how I wanted to like you! How I wanted to find your writing delightful, engaging and witty and your stories compelling and absorbing. How I looked forward to returning to the world of Jane Austen’s novels through such a prolific author that I could stay in that world for months of reading without ever having to be disturbed by more modern times and writing. How disappointed I was, then, when I finished April Lady and found that it was none of the things that I had been anticipating so eagerly.

April Lady tells the story of Nell who is married to the wealthy Lord Cardross. Nell’s brother is a notorious gambler and, when he finds himself unable to pay his debts, Nell steps in to help him, leaving herself unable to pay the extravagant bills for dresses and hats that she has accumulated out of her quarterly allowance from Cardross. Unwilling to tell her husband that she has given the money to her brother, Nell leads him to believe that she herself has been gambling, preferring to incur his disapproval at her actions than his anger towards her brother. He magnanimously pays off all her debts for her, but when Nell discovers another unpaid bill she has forgotten about she finds herself unable to tell him in case he is angry and thinks that she only married him for his money, and so she tries to find ways to raise the money herself with some quite disastrous consequences. At the same time, Cardross has to deal with his sister Letty who has fallen in love with an unsuitable young man lacking in fortune and status but is determined to marry him, whatever it takes.

I did not get on with this book at all, probably because I find the romantic trope in which hero and heroine are deeply in love but each is convinced of the other’s indifference and neither will confess their love despite no obstacles to said affection incredibly annoying. It’s a tired plot that needs either strong characters or great writing to make it come alive and seem fresh and sadly I didn’t find either of those features in April Lady. Instead, what I found was stock characters going through the motions of a formulaic plot, described in lacklustre terms which left me completely unmoved. There is too little social interaction or introspection which might lead to character development, replaced by too much melodrama and wringing of hands. There are a few amusing incidents, such as Nell’s brother holding up her coach dressed as a highwayman in one of the more ridiculous schemes to raise money, but the overall impression that I was left with was that this book was just ok, nothing more. I will say that Heyer has done her research and that the period of the book feels authentic, but I was too irritated at the lack of interesting story to appreciate this properly.

I know that there are a lot of people out there who love Georgette Heyer, and I’m perfectly willing to give her another try if this is considered a particularly poor effort on her part. If however this is standard Heyer fare then I’m going to have to conclude that this writer just isn’t for me, which is fine. I also have Powder and Patch and The Talisman Ring waiting on my shelves; am I likely to enjoy either of these any more than I did this one? Help me out here, Heyer fans.

April Lady by Georgette Heyer. Published by Pan, 1970, pp. 238. Originally published in 1957.

TBR Lucky Dip: April

As I explained in my post about reading plans for the new year, each month I’m going to be using a random number generator to select a book from my TBR pile for me to read, to help me read more widely from my shelves.

This month, the deities of www.random.org have ordained that I should read book number 177. According to my TBR list this means that I am reading…

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Out of his smoke-filled rooms in Baker Street stalks a figure to cause the criminal classes to quake in their boots and rush from their dens of iniquity…

The twelve mysteries gathered in this first collection of Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson’s adventures reveal the brilliant consulting detective at the height of his powers. Problems involving a man with a twisted lip, a fabulous blue carbuncle and five orange pips tax Sherlock Holmes’s intellect alongside some of his most famous cases, including ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ and ‘The Red-Headed League’.

I’m rather pleased with this selection as it gives me the opportunity to start reading the set of lovely Penguin Pocket Classics editions of the Sherlock Holmes stories that I bought from The Book People in February. It also qualifies as another book for the Victorian Literature Challenge (which is progressing well so far, with 5 books read out of a potential 15, all of which have been by different authors) and on top of that it fits in nicely with my April aim of reading slightly chunkier books to slow myself down as it is the second largest volume in the Holmes collection. It’s made up of short stories too, so it will be perfect commuting reading. I think I’ve done well this month!

‘Through England on a Side-Saddle’ by Celia Fiennes

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m attempting to read more non-fiction this year, and so far I seem to be accomplishing most of that in the form of travelogues. There’s something endlessly fascinating about seeing a place through the eyes of someone else, whether it’s somewhere I’ve been before, somewhere I know like the back of my hand, or somewhere I’ll probably never visit. For this reason, I was powerless to resist the lovely box set of English Journeys from Penguin when I saw it on The Book People website. The selection of titles all look enticing, but Through England on a Side-Saddle by Celia Fiennes instantly leapt out at me demanding to be read.

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m attempting to read more non-fiction this year, and so far I seem to be accomplishing most of that in the form of travelogues. There’s something endlessly fascinating about seeing a place through the eyes of someone else, whether it’s somewhere I’ve been before, somewhere I know like the back of my hand, or somewhere I’ll probably never visit. For this reason, I was powerless to resist the lovely box set of English Journeys from Penguin when I saw it on The Book People website. The selection of titles all look enticing, but Through England on a Side-Saddle by Celia Fiennes instantly leapt out at me demanding to be read.

Celia Fiennes was an intriguing, unmarried woman who journeyed around the country on horseback between 1685 and 1703 noting down what she saw. The exerpts from her diary contained in this volume display a country comprising towns teeming with industry, linked by dirty, muddy and treacherous roads.

I’m sure this book would be fascinating to someone researching their local area or looking at the history of England at this time, but as a mere reader I found it hard going. Fiennes does not describe the places she visits so much as she provides an itemised list of exactly what is there: the book is a succession of distances, acreages, numbers of churches and building materials of houses. She is very matter of fact in what she reports and tends to focus on the physical features of the towns and landscapes, rather than talking about the people and their customs. Very occasionally she will deviate from this course to report on a local food or habit, such as her disgust at the smokers in Cornwall where ‘both men, women and children have all their pipesof tobacco in their mouths and soe sit round the fire smoaking’ (p. 79) but this is an unfortunate rarity.

I might have been tempted to read a longer version of Celia Fiennes’ travels to see if this focus on industry and buildings is universal or just showing the bias of the editor who selected the exerpts for this volume, and also to read Celia’s thoughts on the places I have lived and know well, none of which are included in this book. However, the prose, quite simply, is not enjoyable to read. Bearing in mind when Celia was writing I wasn’t expecting modern punctuation and grammar, but equally I hadn’t anticipated her being the queen of the run-on sentence. Some of them go on for several pages and while I could posibly bring myself to forgive her if it was beautiful, elegant, descriptive prose, I cannot when it’s a great big list with some verbs and conjunctions added. To let Celia speak for herself and show you what I mean:

The situation of Lancaster town is very good, the Church neately built of stone, the Castle which is just by, both on a very great ascent from the rest of the town and so is in open view, the town and river lying round it beneath; on the Castle tower walking quite round by the battlements I saw the whole town and river at a view, which runs almost quite round and returns againe by the town, and saw thesea beyond and the great high hills beyond that part of the sea which are in Wales, and also into Westmorelandto the great hills there call’d Furness Fells or Hills being a string of vast high hills together; also into Cumberland to the great hill called Black Comb Hil whence they dig their black lead and no where else, but they open the mine but once in severall yeares; I also saw into Yorkshire; there is lead copper gold and silver in some of those hills and marble and christall also. (pp. 16-17)

And that’s one of the short sentences!

I was also rather disappointed at how absent Miss Celia Fiennes herself was from this book, although admittedly this could be a problem of editing for this particular edition. Even though they were confined to Britain, her journeys seem quite remarkable for a single woman during this period, and I was looking forward to reading about what that was like. I wanted to find out about her own experiences of travelling, any difficulties arising from her unusual circumstances as an unmarried lady on such a journey (albeit with an escort of servants who are occasionally aluded to) and her interactions with the people that she meets. However, with the exception of a few disparaging comments about her landladies and complaints about rye in the bread upsetting her stomach she barely features at all. The account of travelling through England could have been written by anyone, male or female, and that seems a great shame to me.

Please don’t let my review put you off picking up Celia Fienne’s writings, however, if this sort of thing is of interest to you. Nonetheless, I would suggest getting hold of the full volume of her travels rather than this collection of extracts to avoid the disappointment of your local area not being one of those featured in this book, and also not approaching it looking for an entertaining, casual read.

Through England on a Side-Saddle by Celia Fiennes. Published by Penguin, 2009, pp. 87. Originally published in 1947, written in 1698.

‘Miss Buncle’s Book’ by D. E. Stevenson

Although I buy the majority of my books second hand, whether from charity shops, Ebay or Amazon Marketplace, occasionally I will allow myself to purchase a new book or two if they are particularly special. When I discovered sometime in early January that I had to go to Charing Cross for a meeting, meaning that my walk there would take me right past Lamb’s Conduit Street (well, it involved a slight diversion but it was close enough for me) I couldn’t resist paying a visit to the Persephone bookshop that I had read so much about. It was exactly as I had imagined: cosy and inviting with soft lighting, neat stacks of books on every available surface and a comfortingly familiar sort of organised chaos in the office area beyond. Of course, once there it seemed rude not to buy anything and so I came away with Miss Buncle’s Book by D. E. Stevenson, They Were Sisters by Dorothy Whipple, beloved of many a book blogger, and the Persephone 2011 diary (which thankfully doesn’t add to my teetering TBR pile. Still feeling in a Persephone mood after the success of The Victorian Chaise-Longue the day before, I picked up Miss Buncle’s Book, a novel which couldn’t be more different but was equally enjoyable for entirely opposite reasons.

Although I buy the majority of my books second hand, whether from charity shops, Ebay or Amazon Marketplace, occasionally I will allow myself to purchase a new book or two if they are particularly special. When I discovered sometime in early January that I had to go to Charing Cross for a meeting, meaning that my walk there would take me right past Lamb’s Conduit Street (well, it involved a slight diversion but it was close enough for me) I couldn’t resist paying a visit to the Persephone bookshop that I had read so much about. It was exactly as I had imagined: cosy and inviting with soft lighting, neat stacks of books on every available surface and a comfortingly familiar sort of organised chaos in the office area beyond. Of course, once there it seemed rude not to buy anything and so I came away with Miss Buncle’s Book by D. E. Stevenson, They Were Sisters by Dorothy Whipple, beloved of many a book blogger, and the Persephone 2011 diary (which thankfully doesn’t add to my teetering TBR pile. Still feeling in a Persephone mood after the success of The Victorian Chaise-Longue the day before, I picked up Miss Buncle’s Book, a novel which couldn’t be more different but was equally enjoyable for entirely opposite reasons.

Barbara Buncle is a middle aged spinster who has been forced by reduced circumstances to seek additional income and so has written a novel based on the village in which she lives under a pseudonym in the hope of making some money. To her delight her book is published and becomes wildly popular, putting an end to her financial problems. However, the residents of Miss Buncle’s village are less thrilled when they discover that they all feature in the book and many of them are less than flattered. If only they can find the author, the mysterious John Smith, then there is certain to be trouble.

If The Victorian Chaise-Longue wasn’t quite what I expected, Miss Buncle’s Book was everything I had hoped for and more. It is a charming tale of village life which becomes less and less typical as the plot advances, culminating in events which are utterly outlandish, incredibly far-fetched and delightfully entertaining. It is light and fluffy but prevented from being vacuous by the sharp intelligence which lies behind the keen observations of people and their ways which make this book so enjoyable.

Primarily, Miss Buncle’s Book is a novel of character, giving D. E. Stevenson the opportunity to draw portraits of a variety of different people from the doctor to the indomitable Mrs Featherstone Hogg. She is able to convey a great deal of information about her characters without saying things directly, such as in the beginning of the chapter entitled ‘Mrs Carter’s Tea-Party’:

Barbara knew when she saw the china that Mrs Featherstone Hogg was expected, and her spirits fell a degree for she did not like Mrs Featherstone Hogg. Barbara had met Dorothea Bold on the doorstep and they had gone in together, and Miss King and Miss Pretty were there already. But not for these would Mrs Carter have produced her best eggshell cups and saucers, that filmy drawn-thread-work tea-cloth, those lusciously bulging cream buns. (p. 61)

I love the way that Stevenson has focused on the little details like this, making them seem large and important and so drawing the reader into the rather petty and insular world of Silverstream with its little intrigues and high dramas, which is nonetheless a very enjoyable place to be. Persephone have already published the sequel to this book, Miss Buncle Married, and I really hope that they plan to continue republishing the series as I definitely want to spent more time in the company of Barbara Buncle.

Miss Buncle’s Book by D. E. Stevenson. Published by Persephone, 2010, pp. 332. Originally published in 1934.

March Summary

Where on earth has March gone? It seemed to crawl by when I was in the middle of it, but suddenly here we are, six days into April and I haven’t managed to post reviews for a single March book yet. In fact, I still have two lurking around from February. This is a combined result of my getting very behind in February and having been a bit ill this month, so I’ve been playing catch up and I’m not quite there yet. It’s also partly due to my reading books much faster than I review them, so by the time I come to write my reviews I’m already several books further on, making them more difficult to review properly. With this in mind, I’m going to try to read longer books in April so I don’t get quite so far ahead of myself and also to write reviews as I go along and hopefully I’ll be back on track by the end of the month then.

Where on earth has March gone? It seemed to crawl by when I was in the middle of it, but suddenly here we are, six days into April and I haven’t managed to post reviews for a single March book yet. In fact, I still have two lurking around from February. This is a combined result of my getting very behind in February and having been a bit ill this month, so I’ve been playing catch up and I’m not quite there yet. It’s also partly due to my reading books much faster than I review them, so by the time I come to write my reviews I’m already several books further on, making them more difficult to review properly. With this in mind, I’m going to try to read longer books in April so I don’t get quite so far ahead of myself and also to write reviews as I go along and hopefully I’ll be back on track by the end of the month then.

March’s statistics look very much like February’s in that I have once again read 17 books. They totalled 4,358 pages, averaging a rather short 256 pages per book. I found myself enjoying these books a lot more than the previous month’s. I don’t give star ratings here on the blog but I do on LibraryThing and I’ve given a goodly proportion of my books four stars in March. However, I’m still finding that although the majority have been good, enjoyable reads they are still not the sort that stick with me for very long. This is fine, as I do read primarily for my own entertainment and entertaining these books were, but hopefully my aim to read more chunky books in April might lead to a bit less dross. March’s books were:

- April Lady by Georgette Heyer

- More English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs

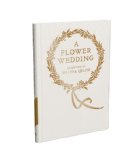

- The Flower Wedding by Walter Crane

- Filboid Studge, the Story of a Mouse That Helped by Saki

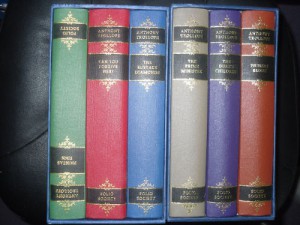

- The Warden by Anthony Trollope

- Fables: Legends in Exile by Bill Willingham

- American Ghosts and Old World Wonders by Angela Carter

- Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister by Gregory Maguire

- The Crimson Petal and the White by Michael Faber

- Far to Go by Alison Pick

- At Freddie’s by Penelope Fitzgerald

- Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies: Sex in the City in Georgian Britain by Hallie Rubenhold

- The Nutmeg Tree by Margery Sharp

- Miss Mapp by E. F. Benson

- Up at the Villa by W. Somerset Maugham

- Alice Hartley’s Happiness by Philippa Gregory

- The Salzburg Tales by Christina Stead

My two favourite books this month couldn’t be more different if they tried. An unexpected stand out was The Flower Wedding by Walter Crane, a gorgeous facsimile of an illustrated poem produced by the V & A Museum to tie in with their new exhibition The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900 which opened this weekend and to which I’ll definitely be paying a visit sometime soon. At the other end of the scale is Michael Faber’s novel of the seedier side of Victorian England, The Crimson Petal and the White. I’ve been reading this one since last year as it’s too big to carry to work with me and so it was read in half hour snatches in the evenings, but it was ever so well written and definitely worth savouring. Notable mentions are also deserved for The Nutmeg Tree by Margery Sharp which was just the sort of light, amusing novel I needed to see me through my convalescence, Up at the Villa by W. Somerset Maugham which came from the Vintage Maugham Collection you may remember I acquired last month, Fables: Legends in Exile by Bill Willingham which has awakened an interest in graphic novels, and The Warden by Anthony Trollope which promises much exciting reading to come. I’m sure I’ll be reading more Trollope in April as he certainly fits the requirements of large, slow books.

My two favourite books this month couldn’t be more different if they tried. An unexpected stand out was The Flower Wedding by Walter Crane, a gorgeous facsimile of an illustrated poem produced by the V & A Museum to tie in with their new exhibition The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900 which opened this weekend and to which I’ll definitely be paying a visit sometime soon. At the other end of the scale is Michael Faber’s novel of the seedier side of Victorian England, The Crimson Petal and the White. I’ve been reading this one since last year as it’s too big to carry to work with me and so it was read in half hour snatches in the evenings, but it was ever so well written and definitely worth savouring. Notable mentions are also deserved for The Nutmeg Tree by Margery Sharp which was just the sort of light, amusing novel I needed to see me through my convalescence, Up at the Villa by W. Somerset Maugham which came from the Vintage Maugham Collection you may remember I acquired last month, Fables: Legends in Exile by Bill Willingham which has awakened an interest in graphic novels, and The Warden by Anthony Trollope which promises much exciting reading to come. I’m sure I’ll be reading more Trollope in April as he certainly fits the requirements of large, slow books.

Less successfully, March also brough about one of only three single star books I’ve read so far this year, and it was a Virago Modern Classic, no less! Try as I might, I just couldn’t get on with The Salzburg Tales by Christina Stead and I’m sure I’ll rant a great deal concerning why when I come to finish that review. Has anyone else out there read this one? What did you make of it?

The list of incoming books is much less intimidating this month (a meagre 34 compared to February’s 59; it’s all relative) thanks to my resolve to give up buying books for Lent. I have to admit that I have fallen off the bandwagon twice so far, although both in extremely forgiveable circumstances I hasten to add: the first occasion was after consigning most of my childhood books that I had kept stored for years to black bin bags after they were ruined by a water damage and the second was on discovering I had a forty-five minute wait for my train and nothing to read as I had finished my book on an earlier train (sometimes I swear I spend my life on trains).

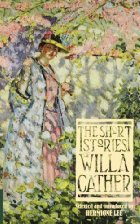

Of course, a fair few managed to sneak in before Lent began on 9th March. Books are tricky like that, I find. As usual, the culprits were mostly Virago Modern Classics which I somehow find myself unable to leave behind in bookshops. In March I acquired Nobody’s Business by Penelope Gilliat, Mad Puppetstown, The Rising Tide and Two Days in Aragon by Molly Keane (I’ve got quite the collection of her books built up now and I really should start reading them), Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick, The Getting of Wisdom by Henry Handel Richardson, Brother Jacob by George Eliot, Devil by the Sea by Nina Bawden, The Thinking Reed by Rebecca West and a little book which looks like it was given away free at some point entitled No Library Is Complete Without Them containing a list of all the Virago Modern Classics at the time it was published and excerpts from several of them to tempt the reader (as if I need any encouragament). Also published by Virago, I picked up The Short Stories of Willa Cather edited by Hermione Lee and a memoir by Joan Wyndham called Dawn Chorus which I’ve already read and thoroughly enjoyed. What good luck I’ve had!

Of course, a fair few managed to sneak in before Lent began on 9th March. Books are tricky like that, I find. As usual, the culprits were mostly Virago Modern Classics which I somehow find myself unable to leave behind in bookshops. In March I acquired Nobody’s Business by Penelope Gilliat, Mad Puppetstown, The Rising Tide and Two Days in Aragon by Molly Keane (I’ve got quite the collection of her books built up now and I really should start reading them), Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick, The Getting of Wisdom by Henry Handel Richardson, Brother Jacob by George Eliot, Devil by the Sea by Nina Bawden, The Thinking Reed by Rebecca West and a little book which looks like it was given away free at some point entitled No Library Is Complete Without Them containing a list of all the Virago Modern Classics at the time it was published and excerpts from several of them to tempt the reader (as if I need any encouragament). Also published by Virago, I picked up The Short Stories of Willa Cather edited by Hermione Lee and a memoir by Joan Wyndham called Dawn Chorus which I’ve already read and thoroughly enjoyed. What good luck I’ve had!

There were only three non-Virago charity shop books this month. After reading lots of enthusiastic praise for Elizabeth Bowen from Carolyn I had to snap up The Collected Stories of Elizabeth Bowen when I saw it on the shelves. It’s a bit big to have as a commuting book, but I’m looking forward to diving in when I next have some time to read at home. The other is The System of the World by Neal Stephenson, the final installment of his Baroque Cycle. I battled to the end of the first volume, Quicksilver, back in December but decided that it was worth the struggle and would continue with the series. I also picked up A Question of Upbringing by Anthony Powell as I’m intrigued by A Dance to the Music of Time and find this slim novella much less intimidating than the larger volumes which contain several parts. We’ll have to see how it goes.

I also had three books come my way from BookMooch in March. The first two are Memoirs of a Master Forger by William Heaney and Any Human Heart by William Boyd, and I can’t remember why I wanted to read them or what they’re about at all. I quite like this though as it means they’ll be a (hopefully) pleasant surprise when I eventually pick them up. The third book is Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, which I’ve read before but don’t own. I’m planning to reread Jane Eyre at some point soon and decided it would be an interesting exercise to read this one again afterwards.

Unusually for me, there were also some new books in March. Walter Crane’s The Flower Wedding was one that I’ve already mentioned and loved. Additionally, I succuumbed to the lure of the Penguin Mini Modern Classics under the irresistible influence of the Waterstones buy-two-get-one-free deal and so Filboid Studge, the Story of the Mouse that Helped by Saki, The Sexes by Dorothy Parker and the intriguingly titled The Mark-2 Wife by William Trevor came home with me. They seem a great way to experiment with new authors. Last but by no means least, I was given a copy of A Life Like Other People’s by Alan Bennett as part of the World Book Night giveaways. I didn’t have time to participate by giving out books myself, so I was really pleased to see this book left carefully on a bench with a tag saying “Please take me home and read me”. How could I possibly refuse?

By far my biggest bookish investment this month has been Trollope. After the success of The Warden I’ve evidently decided that he’s an author I’m going to love and so have bought more of his work. Recently I’ve started buying lovely hardback editions of classic books when I can afford it, and I was lucky enough to find gorgeous box sets of the Folio Society Trollope within my price range on the second hand market. So I now have the next two books of the Barchester series, Barchester Towers and Doctor Thorne, and all six of the Palliser novels (Can You Forgive Her?, Phineas Finn, The Eustace Diamonds, Phineas Redux, The Prime Minister and The Duke’s Children) waiting patiently for me to read them. I’ll definitely be tackling at least one of them this month, probably Barchester Towers. The Barchester books were bought before Lent began, but the Palliser novels were my weekend slip. Technically though, they were bought on a Sunday and Lent doesn’t count on Sundays (I’ll keep telling myself this).

By far my biggest bookish investment this month has been Trollope. After the success of The Warden I’ve evidently decided that he’s an author I’m going to love and so have bought more of his work. Recently I’ve started buying lovely hardback editions of classic books when I can afford it, and I was lucky enough to find gorgeous box sets of the Folio Society Trollope within my price range on the second hand market. So I now have the next two books of the Barchester series, Barchester Towers and Doctor Thorne, and all six of the Palliser novels (Can You Forgive Her?, Phineas Finn, The Eustace Diamonds, Phineas Redux, The Prime Minister and The Duke’s Children) waiting patiently for me to read them. I’ll definitely be tackling at least one of them this month, probably Barchester Towers. The Barchester books were bought before Lent began, but the Palliser novels were my weekend slip. Technically though, they were bought on a Sunday and Lent doesn’t count on Sundays (I’ll keep telling myself this).

My other slip occurred when I found myself at a train station with a long wait and, inexplicably, nothing to read. I headed off to a charity shop intending to come back with just the one book but somehow managed to return with three of the things all by the same author: Perfume from Provence, Sunset House: More Perfume from Provence and There’s Rosemary…There’s Rue by Lady Winifred Fortescue. In my defence, they’re the sort of delightful books which are out of print and looked as though they would be impossible to get hold of again. Besides, it would have been cruel to separate them…

So, it seems as though I may not be sticking to a total book buying ban (that was a little optimistic, I grant you) but at least it’s curbing my acquisitions rather substantially. We’ll see what April brings. (One day I swear I’ll get a camera for these posts, honest.)

Virago Book Club Event: Linda Grant

On Wednesday, I was one of thirty members of Virago’s Book Club lucky enough to attend their first live event: an evening with Linda Grant discussing her most recent book and the first Book Club title, We Had It So Good. I knew it was bound to be an interesting evening for me as, although it was well-written and interesting, I hadn’t particularly enjoyed the book when I read it earlier this year (two entirely different things: there are books which are perfectly written which just don’t click for me and stuff which is horrible literature that I devour avidly) and it certainly proved to be so. I came away from the evening with a much greater appreciation for the novel and why it does what it does, including the aspects that I personally didn’t like.

On Wednesday, I was one of thirty members of Virago’s Book Club lucky enough to attend their first live event: an evening with Linda Grant discussing her most recent book and the first Book Club title, We Had It So Good. I knew it was bound to be an interesting evening for me as, although it was well-written and interesting, I hadn’t particularly enjoyed the book when I read it earlier this year (two entirely different things: there are books which are perfectly written which just don’t click for me and stuff which is horrible literature that I devour avidly) and it certainly proved to be so. I came away from the evening with a much greater appreciation for the novel and why it does what it does, including the aspects that I personally didn’t like.

We Had It So Good is the only book of Linda Grant’s that I’ve read, and so it was difficult to try to guess what she might be like from just this one experience; it turns out that she is warm, lively, very entertaining to hear speak and the owner of some eminently covetable shoes. The evening started with Linda passing around a photograph of herself and some friends in Venice in the 1970′s and reading some letters that she had written to a friend around that time (rather brave considering how frank they were) to provide some context for Stephen and Andrea, the book’s main characters. After we’d all had a chuckle at the 70′s fashions, music and attitudes that the letters and picture recalled (and a small detour regarding The Archers’ book club), we settled down to listen to Linda answering questions from her editor, Lennie Goodings, with frequent interjections from the enthusiastic audience members. It was a lovely, friendly informal occasion and I learned a lot.

Linda started by explaining what inspired the book which, appropriately enough for this book, was a combination of personal and political factors. On the one hand, a chance meeting with an old hippie acquaintance who now runs a million pound advertising business made her curious as to how someone got from a to b like that, and on the other the incidents of September 11th caused her to look back at her generation and think, as the title says, we had it so good. She went on to talk about the characters (Max was our universal favourite) and expressed her concerns that a lot of reviews (my own included, to a certain extent) were overly concerned about whether the characters were likeable or not, an issue which is really besides the point of the novel. I think we all like to like the people we read about (if you’ll pardon the overuse of ‘like’ there) but would agree that it’s not necessarily an issue as long as they are interesting in their unlikeability. Besides, the point was made that the novel takes place over such a long period that you would never like a person continually or agree with all their choices over an equivalent time period in real life, so why should we expect to in a book? The main point is that characters should be credible, engage the reader and provoke a reaction.

Linda started by explaining what inspired the book which, appropriately enough for this book, was a combination of personal and political factors. On the one hand, a chance meeting with an old hippie acquaintance who now runs a million pound advertising business made her curious as to how someone got from a to b like that, and on the other the incidents of September 11th caused her to look back at her generation and think, as the title says, we had it so good. She went on to talk about the characters (Max was our universal favourite) and expressed her concerns that a lot of reviews (my own included, to a certain extent) were overly concerned about whether the characters were likeable or not, an issue which is really besides the point of the novel. I think we all like to like the people we read about (if you’ll pardon the overuse of ‘like’ there) but would agree that it’s not necessarily an issue as long as they are interesting in their unlikeability. Besides, the point was made that the novel takes place over such a long period that you would never like a person continually or agree with all their choices over an equivalent time period in real life, so why should we expect to in a book? The main point is that characters should be credible, engage the reader and provoke a reaction.

The most interesting part of the evening was definitely learning about the writing process and the decisions that Linda had made when writing and revising the book. Apparently the chapter which holds the key to understanding the outspoken, unlikeable Grace (ah, I’m back to liking again) was originally Grace’s first chapter, rather than placed at the end as a shocking revelation as it is in the published edition. It was moved to the end for greater impact, but she says that even now she isn’t sure which placement works best and that the chapter could go in either place. Also fascinating was her decision not to have the novel follow quite the trajectory that she had initially intended, with Max or Marianne being killed or wounded in the September 11th attacks. This was a change that she made after the child of a close friend was seriously injured in a similar attack, and she felt that to write about it with the insider knowledge that she shouldn’t have would be exploitative and wrong, so instead tragedy happens off to the side and is not the main focus of the novel. It was wonderful to learn of such a sensitive decision full of integrity, even if it does mean that We Had It So Good is, in her opinion, not the book it would have been had her original idea been followed through.

In true book club fashion the evening began and ended with copious quantities of cake, possibly more than the people at Virago had intended after someone who had been unable to attend the event dropped off a very impressive cake in the shape of Linda’s book! I left having had a thoroughly good time, with a greater understanding of We Had It So Good, a desire to read another of Linda Grant’s books (probably The Clothes on Their Backs which was mentioned quite a lot and sounds rather good), and a canvas bag containing a proof copy of an upcoming book (particularly welcome given the current embargo on book buying). For pictures from the evening, take a look at Virago’s blog post. Thanks very much to the Virago team for organising such an interesting event and for inviting me along.

‘The Victorian Chaise-Longue’ by Marghanita Laski

Although I’ve only read one book published by Persephone before now (the delightful Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson) this, combined with the numerous reviews I’ve read for books from this publisher on other blogs, has been sufficient to create a preconception in my mind of what a Persephone book will typically be like. I expect them to be sweet, charming and domestic in focus with a lively wit and intelligence. So when I needed relief from the postmodern meanderings of Paul Auster (which are undoubtedly very clever but, frankly, made my brain hurt more than a little) I turned to my newest Persephone acquisition which I had fortuitously discovered on the shelves of Oxfam that very day. However, these ideas I had have been checked already at only my second Persephone book, The Victorian Chaise-Longue by Marganita Laski. Laski’s book may have the expected domestic setting and it is definitely clever, but goodness me it’s dark! What I expected to be a cosy, pleasant read turned out to be a little slice of nightmare, but for all it flouted my expectations it as nevertheless a stunning book.

Although I’ve only read one book published by Persephone before now (the delightful Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson) this, combined with the numerous reviews I’ve read for books from this publisher on other blogs, has been sufficient to create a preconception in my mind of what a Persephone book will typically be like. I expect them to be sweet, charming and domestic in focus with a lively wit and intelligence. So when I needed relief from the postmodern meanderings of Paul Auster (which are undoubtedly very clever but, frankly, made my brain hurt more than a little) I turned to my newest Persephone acquisition which I had fortuitously discovered on the shelves of Oxfam that very day. However, these ideas I had have been checked already at only my second Persephone book, The Victorian Chaise-Longue by Marganita Laski. Laski’s book may have the expected domestic setting and it is definitely clever, but goodness me it’s dark! What I expected to be a cosy, pleasant read turned out to be a little slice of nightmare, but for all it flouted my expectations it as nevertheless a stunning book.

First, the reader is introduced to Melanie, a 1950′s wife and mother who has been confined to her bed since the birth of her child as she was taken ill with tuberculosis and has consequently been unable to see her child in case the excitement is too much for her weakened constitution. As the novella starts, the doctor decides that Melanie is well enough to spend the afternoon in a different room to give her a change of scenery and she is carried to the Victorian chaise-longue of the title, a peculiarly compelling item of furniture which Melanie purchased in an antique shop whilst shopping in search of a crib for her coming baby. There, she falls asleep, but on waking Melanie finds herself no longer in the 1950′s but back in 1864 and so the nightmare begins.

I thought that Melanie (or Milly as she is known in 1864) was a very interesting character. When the reader sees her in the 1950′s she comes across as docile and rather vacuous, relying on her husband, the nurse and the doctor without any particular opinions or influence of her own, but there is still the feeling that there is something behind her perfect housewife exterior, an intelligence which she keeps hidden for some reason. Ironically, it is only when she is transported back to 1864 that this is revealed: in the modern setting the reader is kept out of Melanie’s head, wheareas all of the Victorian section is shown entirely through her thoughts and reactions. She starts to express her thoughts and try to act only at the time when she is most helpless and she no longer has other people around her to act as props. The nightmare experience of finding herself in an alien time period is the catalyst which forces her to become independent and so in a peculiar way the reader watches her becoming free even as she is trapped.

The most thought provoking aspect of this book is its ambiguity; as I’ve observed, the reader only experiences the time travel through Melanie’s mind and so it is impossible to say what exactly is going on. Is she dreaming? Is she mad? Has she really travelled in time? She retains her modern sensibilities and is aware of herself as Melanie, not Milly, but also has some of Milly’s memories, so who is she really? Has she regressed to a past life? Can she get back or is she trapped? If she dies in the past, what happens to her in the present? The reader is just as confused and disoriented by this sudden, unpredicted change in the direction of the narrative as Melanie is and so is drawn into her panic and horror.

I found this book very effective and I’m very grateful to Persephone for introducing me to a wonderful new author, even if this wasn’t the book that I was expecting at all.

The Victorian Chaise-Longue by Marghanita Laski. Published by Persephone, 1999, pp. 101. Originally published in 1953.

‘Tam Lin’ by Pamela Dean

O I forbid you, maidens a’,

O I forbid you, maidens a’,

That wear gowd on your hair,

To come or gae by Carterhaugh,

For young Tam Lin is there.

Fairy tales and folk stories were a huge part of my childhood and have continued to be so as I’ve become older. I had them read to me by my parents; I read them to myself; I listened to storytellers weaving their own versions of the tales sat around campfires and in tents; I watched them performed on the stage in ballets, pantomimes and plays; and I heard them sung. The ballad of Tam Lin was a story that I first encountered through the music of Steeleye Span (a nice video set to Steeleye Span singing Tam Lin can be found here for your entertainment), which made up a fair part of my parents’ record collection. I was entranced by the music and the stories and I haven’t stopped loving folk music or folk tales ever since then.

In the ballad, Tam Lin is a young man who lives in the forest of Carterhaugh and takes either a possession or the virginity of any girl who passes through. When Janet is caught by him plucking a rose there, she insists that she owns Carterhaugh as her father has given it to her. When she returns home, as is the way in folk tales, she soon discovers she is pregnant, but will only say that the father is an elf and will not reveal who he is. She goes back to Tam Lin who forbids her to terminate the pregnancy and tells her that he is in fact a human but was claimed by the Fairy Queen after he fell from his horse. Every seven years the fairy court pays a tithe to hell and he fears that this year he will be part of the sacrifice and only Janet can save him. That Halloween, Janet waits at the crossroads and watches as a procession of fairies ride past until finally Tam Lin comes by on a white horse. Janet pulls him from his mount and must keep hold of him as the Fairy Queen transforms him into a succession of different creatures in order to attempt to make Janet let go. Eventually, he is turned into a burning brand, upon which Janet plunges him into the well and he turns back into a man, she wraps him in her green mantle and he is hers.

The story is one that I’ve always found fascinating, not least because it features a woman rescuing her captured lover for a change, and so I was thrilled to learn that Pamela Dean had written a novel based on the ballad, also called Tam Lin. In Dean’s take on the story, Janet is an English student just starting out at Blackstock College. There she not only has to deal with the usual teenage anxieties of studying, getting along with her roommates and discovering sex, but also more mysterious concerns. What exactly is it about the strange and aloof Classics department that makes them stand apart from everyone else? Who is the ghost that haunts their dorm room throwing old books out of the window, and why did she kill herself? Who are the Classics boys who talk in verse and seem to have known each other forever and what makes them so different?

The more I think about this book, the more profoundly it irritates me. This is a book which has 33 five star reviews out of 48 on Amazon and is about a topic I love (clearly I’ve missed something), so I started reading with high hopes, turning the pages in eager anticipation of spotting a clever, subtle reference to the ballad. And I waited, and waited and waited. With the exception of a rather painfully direct midnight Halloween procession on horseback from the Classics department part way through the book, it isn’t until the final fifty pages (a hundred if I’m feeling generous) that the story of the ballad really starts to play a part; in a book which is supposedly based on the ballad, I expected it to have a little more influence than that. For that matter, I’m not sure why an author would spend so long creating a world which is totally different from that of the ballad only to insert large chunks of the original storyline exactly as they happen rather than subtly adapting it. This would have been less of an issue had it not been for the fact that, by the time the book finally got to this point, I couldn’t bring myself to care as the story beforehand had been so lacklustre.

Without the prevailing influence of the ballad of Tam Lin, Dean’s Tam Lin is mostly just a story of university life. We watch Janet study for exams, spend time in the library and go to classes all of which I unfortunately found rather dull. The characters were so very pretentious that I couldn’t sympathise with any of them and the relationships between them all felt shallow and unreal. There isn’t even any romance or desperation in Janet’s decision to pull Tom Lane (get it?) off his horse and save him (yes, it happens as obviously as that). As these relationships are the driving force behind the book I didn’t find much to enjoy, I’m afraid. In addition to the mundane university story, Dean has added a few of her own supernatural subplots, none of which tie in with the original ballad and none of which were explained to my satisfaction by the time the end of the novel rolled tediously round. It was a huge disappointment.

Not only did the characters have unbelievable relationships, they also had unbelievable conversations with one another. It seems that they hardly ever opened their mouths without uttering a line or five of a famous poem or making a clever literary, grammatical or historical pun and at times they speak more or less entirely in quotations from other works. Picked at random, here’s a typical interchange between two characters:

“Will you talk sense for once!” said Janet, losing all patience.

“Sir,” said Robin, in an uncanny imitation of the Korean actor who had played Hamlet a year ago, “I cannot. Cannot what, my lord?” he apostrophized himself sharply, as Rosencrantz had spoken to Hamlet. “Make you a wholesome answer,” he said mournfully, as Hamlet. “My wit’s diseased.” He reverted to his own expression, and looked hopefully at Janet.

“Oh, go away!” said Janet. “You’re enough to try the patience of a saint. Leave me alone. I’ll see you at supper. Don’t say it!” she added furiously, as Robin seemed about to add some of Hamlet’s observations about Polonius and the worms, which would, to a grasshopper mind like his, have been amply suggested by the word “supper”.

“I shan’t say it,” said Robin, getting up off the bed and bowing to her. “Nobody is dead yet.” He turned with considerable aplomb and shut the door with a dignified click that spoke volumes more than Thomas’s slam.

“We’re all mad here,” said Janet after a moment, and turned resolutely back to Pope. (p. 329)

Not only does making your eighteen year old characters speak like this make any form of realism impossible, it’s also incredibly abrasive. There were times when I wanted to strangle the next person to say “I cry you mercy” instead of just apologising.

Now, I’m all in favour of making clever literary allusions and judicious use of intertextuality: Chaucer and Shakespeare both did it to great effect, so it’s hard to argue that one. Dean, however, is not a Chaucer or a Shakespeare. They wrote works that are brilliant in their own right and the allusions and quotations to other texts serve to illuminate and expand upon the message of their own writing, whereas in this book the clever lines from other people are a substitute for the text doing anything clever itself. In fact, there’s no space for any original intelligence, so full is this book of thoughts, ideas and words borrowed from other sources. I felt that it uses other people’s brilliance to disguise its own lack thereof, and also as a way for the author to show of how many famous books she’s read. It all came across as rather self-indulgent and didn’t sit well with me.

It’s going to come as no surprise that this book will be searching for a new home soon. Why is it always the books with the prettiest cover art that are the most disappointing this year?

Tam Lin by Pamela Dean. Published by Tor, 1992, pp. 468. Originally published in 1990.

TBR Lucky Dip: March

As I explained in my post about reading plans for the new year, each month I’m going to be using a random number generator to select a book from my TBR pile for me to read, to help me read more widely from my shelves.

This month, the deities of www.random.org have ordained that I should read book number 316. According to my TBR list this means that I am reading…

Death of a Naturalist by Seamus Heaney

With its lyrical and descriptive powers, Death of a Naturalist marked the auspicious debut of one of the century’s finest poets. Seamus Heaney was born in Mossbawn, Co. Derry, Northern Ireland. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995.

This is a book that I have in a box set of Faber poetry books, most of which I’ve dipped into before but not read properly. I’m excited about this selection, as I’ve not read any Heaney since he was on the syllabus for GCSE poetry, but I remember liking his writing and it will be good to rediscover him after all this time.

I think the random number generator was smiling on me with this choice: evidently it knew that I’d left it rather late in the month to choose a book and so it kindly (and entirely randomly, I hasten to add) selected what is possibly the slimmest volume in my TBR pile at a mere 46 pages. I should be able to squeeze such a little book in before March is over.

‘Diary of a Nobody’ by George and Weedon Grossmith

One of the best things about taking part in the Victorian Literature Challenge is that it has made me aware that the scope of Victorian literature is much wider than I had previously anticipated. It isn’t just doorstop sized books featuring worthy governesses, scheming gentlemen and the deserving poor; there’s also a lot of slimmer, sillier volumes which are genuinely good fun. The Diary of a Nobody was originally serialised in Punch magazine and so definitely falls into the latter category. When I stumbled upon this delightful little hardcover 1940′s edition, complete with dust jacket and containing all the original illustrations, in my local Oxfam bookshop it had to come home with me.

One of the best things about taking part in the Victorian Literature Challenge is that it has made me aware that the scope of Victorian literature is much wider than I had previously anticipated. It isn’t just doorstop sized books featuring worthy governesses, scheming gentlemen and the deserving poor; there’s also a lot of slimmer, sillier volumes which are genuinely good fun. The Diary of a Nobody was originally serialised in Punch magazine and so definitely falls into the latter category. When I stumbled upon this delightful little hardcover 1940′s edition, complete with dust jacket and containing all the original illustrations, in my local Oxfam bookshop it had to come home with me.

As the title suggests, the book is a fictionalised diary of fifteen months in the life of an ordinary man . Mr Charles Pooter is a middle class man, living in a typical London suburb, who works at a bank. As he goes about his daily life, his aspirations are constantly frustrated by his troubles with his workmates, his layabout son, the tradespeople and the blasted scraper outside his door.

The aspect of this book that I enjoyed best was definitely Mr Pooter himself. In spite of his pompous manner, his ineffectual nature, his jokes that fall flat and his highly inflated opinion of himself, I found him somehow endearing. I rarely sympathised with him, he often frustrated me, but I liked him nonetheless. His ill-advised notions (perhaps most delightfully deciding to paint everything with red enamel paint, leading to a rather bloody-looking bath after it dissolves in the hot water) often had me giggling. His constantly frustrated narration is rather entertaining:

The aspect of this book that I enjoyed best was definitely Mr Pooter himself. In spite of his pompous manner, his ineffectual nature, his jokes that fall flat and his highly inflated opinion of himself, I found him somehow endearing. I rarely sympathised with him, he often frustrated me, but I liked him nonetheless. His ill-advised notions (perhaps most delightfully deciding to paint everything with red enamel paint, leading to a rather bloody-looking bath after it dissolves in the hot water) often had me giggling. His constantly frustrated narration is rather entertaining:

By-the-by, I will never choose another cloth pattern at night. I ordered a new suit of dittos for the garden at Edwards’, and chose the pattern by gaslight, and they seemed to be a quiet pepper-and-salt mixture with white stripes down. They came home this morning, and, to my horror, I found it was quite a flash-looking suit. There was a lot of green with bright yellow-coloured stripes.

I tried on the coat, and was annoyed to find Carrie giggling. She said: “What mixture did you say you asked for?”

I said: “A quiet pepper-and-salt.”

Carrie said: “Well, it looks more like mustard, if you want to know the truth.”

How interesting that the Victorians evidently said “pepper and salt” instead of “salt and pepper” as I always hear it nowadays. The things you learn from books.

I also appreciated the fact that not every entry was intended to be funny, which made it feel more like a real diary, with someone just recording the mundane things that had happened that day. Often these entries provided build up to an amusing anecdote, but it nonetheless adds a flavour of realism to an otherwise comic novel.

Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, illustrated by Weedon Grossmith. Published by Pan, 1947, pp. 171. Originally published in 1892