Review: ‘Liza of Lambeth’ by W. Somerset Maugham

If you were, hypothetically, to have your train delayed by over four hours one evening, taking your total journey home time from a little over two hours (which now seems almost reasonable by comparison) to six and a half hours, you’d definitely need a book or two with you to keep you sane. Ideally, you want something entertaining, lighthearted and vaguely escapist to distract you from the fact that you’re stuck on a train platform next to five stationary trains and many, many angry commuters. Possibly you want something easy so you aren’t too confused when you have to stop reading every five minutes to listen to announcements about how sorry SouthWest Trains are (after a delay of more than an hour they go from being ‘sorry’ to ‘very sorry’). What you don’t want is to be reading a depressing story about the harsh reality of life for women in London’s East End during the late Victorian era. Still, it’s difficult to plan ahead for train delays and so when I was stuck in this complete and utter chaos back in June I had to make do with what I had and read Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham.

If you were, hypothetically, to have your train delayed by over four hours one evening, taking your total journey home time from a little over two hours (which now seems almost reasonable by comparison) to six and a half hours, you’d definitely need a book or two with you to keep you sane. Ideally, you want something entertaining, lighthearted and vaguely escapist to distract you from the fact that you’re stuck on a train platform next to five stationary trains and many, many angry commuters. Possibly you want something easy so you aren’t too confused when you have to stop reading every five minutes to listen to announcements about how sorry SouthWest Trains are (after a delay of more than an hour they go from being ‘sorry’ to ‘very sorry’). What you don’t want is to be reading a depressing story about the harsh reality of life for women in London’s East End during the late Victorian era. Still, it’s difficult to plan ahead for train delays and so when I was stuck in this complete and utter chaos back in June I had to make do with what I had and read Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham.

In Liza of Lambeth, Maugham draws on his own experiences as a trainee doctor who would frequently be called to attend on people in the poorer areas of London. Liza is an eighteen year old factory worker who enjoys dancing, drinking, wearing new clothes and generally living life to the full. She lives with her aging mother, walks out with Tom and spends time with her friend Sally. All this changes when a new family move in to the street and the father, the much older Jim Blakestone, starts paying attention to Liza. Even though Jim is married, Liza finds herself unable to resist him and so begins her downfall.

Like Up at the Villa which I read earlier last year, this book is not at all the sort of book that it seems to be from the first chapter, which is so full of stereotypical cockney merriment and hijinks that I half expected Dick van Dyke to pop up and start performing a song and dance routine. However, it does not take long for Maugham to reveal the hard reality of the daily lives of the inhabitants of Vere Street, in which all men beat their wives, women fight each other, and death is an ever-present possibility. None of the characters ever seem particularly unhappy with their lot in life, facing their relative poverty with equanimity and good cheer, prosaically discussing the practicalities of having insured a person as they lie dying or excusing their husbands’ violence as just being down to drink. Of course, this makes it all the more heart-breaking and shocking to read as a modern reader or even a Victorian reader of a higher class with different expectations of what life should be like.

There were two things that I found irritating in this book (although do remember that I was predisposed to be irritated anyway). The first is Maugham’s attempt to reproduce a cockney accent in his writing. Although it is usually possible to work out what characters were saying, unlike in some books where attempts at written accents make a character’s speech virtually unintelligible (Lorna Doone, I’m looking at you), it is rather grating. I know Maugham wants to stop readers from imagining the inhabitants of Vere Street speaking in perfect RP, but this is already implied through vocabulary choice and the accent reproduction was a step too far for me. The other thing was Liza and Jim’s relationship, which Maugham makes no attempt to explain. The attraction for older, married Jim is obvious, but why does Liza fall in love with him? She knows he is married with a daughter only a few years younger than her, she knows he beats his wife, she knows he gets drunk and yet still she goes with him. When Liza is first introduced, she is such a feisty and opinionated character that I expected her to slap Jim and screech at him when she first feels him surreptitiously stroking her leg as he sits beside her in the cart, but she keeps quiet at the time and later lets him follow her home and kiss her. Perhaps her downfall is supposed to seem all the more tragic because her love is inexplicable and illogical, but I personally found it too unbelievable.

I would have probably enjoyed this book more had I not read the introduction first, not because Maugham gives away anything of the story but because the writing in it out-classes that of the actual story completely. The introduction is far more polished, professional and engaging and I found it more interesting than the story itself. Liza of Lambeth was Maugham’s first novel, written when he was only twenty-three, and the introduction in the Vintage edition of the book was written for a retrospective collection of his works when he was a much older man with a much better developed writing style, so the discrepancy is entirely understandable. Nevertheless, the comparison that it invites is not favourable and so this is another introduction which would be better moved to the end of the book, I think.

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham. Published by Vintage, 2000, pp. 139. Originally published in 1897.

Review: ‘American Gods’ by Neil Gaiman

When I came to select a book to read after finishing Anderby Wold, I don’t think I could have picked something much more different than Neil Gaiman’s American Gods had I been trying deliberately to do so. The former is provincial, understated, realistic and oh so English, while the latter is sweeping, outrageous, mythological and (despite its English author) undeniably American.

When I came to select a book to read after finishing Anderby Wold, I don’t think I could have picked something much more different than Neil Gaiman’s American Gods had I been trying deliberately to do so. The former is provincial, understated, realistic and oh so English, while the latter is sweeping, outrageous, mythological and (despite its English author) undeniably American.

The novel opens shortly before the release of central character Shadow from prison, when he is summoned to the office to hear news of his wife Laura’s death in a car crash. On the plane home, he is accosted by a strange man calling himself Mr Wednesday who claims to be a former god embroiled in a war with the new gods. Little does Shadow know it, but he is soon to find himself playing a key role in this conflict, embroiled in a world of gods and legends fighting for survival in the improbable setting of the American Midwest.

On the one hand, I really like the idea of American Gods. I like the thought of all the old gods and spirits emigrating from their native lands along with their believers and eventually finding themselves having to exist in 20th century small town America. I love the little mythic episodes which litter the novel, detailing the story of a particular deity which isn’t relevant to the plot per se, but which helps to build up the whole picture of the world that Gaiman is creating. I thoroughly enjoyed picking out all of the elements of folklore, myth and fairytale, even if I think this may have resulted in me working a lot of things out much sooner than I was probably supposed to. I think that the idea that bizarre tourist attractions with no real significance are the modern day places of pilgrimage is completely inspired and it never failed to make me smile. I like the idea of the gods being in conflict; it made the story feel like a myth that had been brought thoroughly up to date. However, therein lies one of my problems with the book.

Why is there suddenly this conflict between the gods and material things? The commandment ‘Thou shalt not commit idolatry’ would suggest that people have been worshipping things beside the approved deities for quite some time now, so it seems a little bit odd that this has been a non-issue until the 20th century. The Norse gods who are the focus of this book have been quite firmly out of favour for at least a thousand years, so why are they at the forefront of the conflict? Surely if anyone is fighting off the ‘new’ gods of materialism it should be some strange trinity of Jesus, Buddah and Mohammed, not those whose worship was already considered a bit archaic when Beowulf was written down? I enjoyed the premise, but I didn’t really believe in it, if that makes sense.

Ultimately, I had the same criticism of American Gods that I did of Stardust when I read that back in 2010: I really like the ideas that Gaiman comes up with, but I’m not 100% convinced by what he does with them. I found myself reading American Gods and interrupting myself by thinking ‘This would be so much better if it had been written by someone else’. I think my ideal Neil Gaiman book is possibly written by Terry Pratchett (yes, I am aware of Good Omens; no, I haven’t read it yet). That’s not to say that I think he’s a bad writer or even that I don’t enjoy his books, it’s simply that I don’t think I quite click with him. I know it’s unfair to judge a book by what you hoped it would be, but I wanted American Gods to be more epic, more humorous, more sinister and, well, just more than what it turned out to be.

That said, there were sections of writing that I absolutely loved. Samantha Black Crow’s bizarre creed was one of my favourite parts of the whole novel:

I can believe things that are true and things that aren’t true and I can believe things where nobody knows if they’re true or not.

I can believe in Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny and the Beatles and Marilyn Monroe and Elvis and Mister Ed. Listen – I believe that people are perfectable, that knowledge is infinite, that the world is run by secret banking cartels and is visited by aliens on a regular basis, nice ones that look like wrinkled lemurs and bad ones who mutilate cattle and want our water and our women.

I believe that the future sucks and I believe that the future rocks and I believe that one day White Buffalo Woman is going to come back and kick everyone’s ass. I believe that all men are just overgrown boys with deep problems communicating and that the decline in good sex in America is coincident with the decline in drive-in movie theaters from state to state.

I believe that all politicians are unprincipled crooks and I still believe that they are better than the alternative. I believe that California is going to sink into the sea when the big one comes, while Florida is going to dissolve into madness and alligators and toxic waste.

I believe that antibacterial soap is destroying our resistance to dirt and disease so that one day we’ll all be wiped out by the common cold like martians in War of the Worlds.

I believe that the greatest poets of the last century were Edith Sitwell and Don Marquis, that jade is dried dragon sperm, and that thousands of years ago in a former life I was a one-armed Siberian shaman.

I believe that mankind’s destiny lies in the stars. I believe that candy really did taste better when I was a kid, that it’s aerodynamically impossible for a bumble bee to fly, that light is a wave and a particle, that there’s a cat in a box somewhere who’s alive and dead at the same time (although if they don’t ever open the box to feed it it’ll eventually just be two different kinds of dead), and that there are stars in the universe billions of years older than the universe itself.

I believe in a personal god who cares about me and worries and oversees everything I do. I believe in an impersonal god who set the universe in motion and went off to hang with her girlfriends and doesn’t even know that I’m alive. I believe in an empty and godless universe of causal chaos, background noise, and sheer blind luck.

I believe that anyone who says sex is overrated just hasn’t done it properly. I believe that anyone who claims to know what’s going on will lie about the little things too.

I believe in absolute honesty and sensible social lies. I believe in a woman’s right to choose, a baby’s right to live, that while all human life is sacred there’s nothing wrong with the death penalty if you can trust the legal system implicitly, and that no one but a moron would ever trust the legal system.

I believe that life is a game, that life is a cruel joke, and that life is what happens when you’re alive and that you might as well lie back and enjoy it.

It’s clever, it’s witty, it’s completely insane yet somehow rings true and I wish the whole novel had been more along those lines.

This is sounding like a very negative review, but I did honestly enjoy the book, just not as much as expectations had led me to believe I would. I’ll continue to read Neil Gaimain’s books for the wonderfully innovative ideas that he comes up with. Who knows, maybe his writing will grow on me the more I read?

American Gods by Neil Gaiman. Published by Headline Review, 2005, pp. 656. Originally published in 2001.

Moby Dick Part One

Moby Dick may be a classic of American literature. It may (apparently, so I’m told) have one of the most famous opening lines of any novel. None of that prevented me from coming to this book knowing almost nothing about it and from being faintly baffled when I opened it to the words ‘Call me Ishmael‘. Ishmael? Who is this upstart? Moby Dick is about Captain Ahab and his obsessive hunt for the great white whale, isn’t it? Isn’t it??

Moby Dick may be a classic of American literature. It may (apparently, so I’m told) have one of the most famous opening lines of any novel. None of that prevented me from coming to this book knowing almost nothing about it and from being faintly baffled when I opened it to the words ‘Call me Ishmael‘. Ishmael? Who is this upstart? Moby Dick is about Captain Ahab and his obsessive hunt for the great white whale, isn’t it? Isn’t it??

I’m sure I’m not alone in assuming that Moby Dick was going to be some sort of Boys’ Own Adventure Story of whaling boats, deadly peril and adventure on the high seas (in much the same way that the uninitiated think that Robinson Crusoe is some sort of novelised, jolly 18th century version of a Bear Grylls television show, in blissful ignorance of the tedious pot making, goat rearing, navel gazing and inexplicable bear hunting which actually comprise most of the novel). However, a quarter of the way through the novel and, while the Pequod has finally put to sea, it’s only five pages ago that we’ve so much as set eyes on Captain Ahab, the central character in my imagined version of the story, and although there’s been frequent references to them, there’s been nary a whale to be seen. I’m swiftly approaching the conclusion that Moby Dick is not a plotty book.

If it lacks some of the elements that I expected, it compensates for this by having a surprising number of things that I did not anticipate. I had expected it to have a similar sort of style to English novels that I have read from around the same period, but in fact Robinson Crusoe seems a reasonably accurate comparison: in spite of its having been written 130 years earlier than Melville’s work, these two novels have far more in common than Moby Dick does with many other Victorian novels. Like Crusoe, Moby Dick takes a story which you might expect to be all about plot and instead makes it discursive and rambling. Melville doesn’t summarise something when he can explain it in full, and he doesn’t limit himself to just explaining something in full when he can also philosophise about that. Nothing that Ishmael waxes lyrical about should be particularly relevant or important, but somehow everything is made to seem so. I’m not saying it’s a narrative style that I’m particularly enjoying, but I can see what he’s doing and it’s interesting to watch.

Although we have yet to go to sea, whaling has been a constant presence throughout the first quarter, and, while it will (I assume) drive the action later in the book, we are first introduced to it as a theoretical, philosophical thing. Ishmael provides a passionate defence of whaling, and Melville uses it to illustrate many of his religious points:

Yes, there is death in this business of whaling — a speechlessly quick chaotic bundling of man into Eternity. But what then? Methinks we have hugely mistaken this matter of Life and Death. Methinks that what they call my shadow here on earth is my true substance. Methinks that in looking at things spiritual, we are too much like oysters observing the sun through the water, and thinking that thick water the thinnest of air. Methinks my body is but the lees of my better being. In fact, take my body who will, take it I say, it is not me. And therefore three cheers for Nantucket; and come a stove boat and a stove body when they will, for stave my soul, Jove himself cannot.

I found the rather long-winded sermon about Jonah interesting because it put me in mind of all the medieval associations with Jonah and the whale. In the middle ages (I know this is broad, but it’s difficult to pin down beliefs like this) Christian scholarship liked to find foreshadowing of the coming of Christ and his death and resurrection hidden in earlier Bible stories. The whale was a widely used representation not only of the devil but of hell, and so they saw Jonah as a type of Christ. Both were taken from the world (either by crucifixion or being swallowed by a giant fish), both spent three days in hell and both emerged triumphant to proclaim the good news and spread God’s word. While I think it’s going to be a bit of a stretch to see the whalers as Christ-figures, this does make me assume that the period spent whaling is going to be, effectively, time spent in hell, after which the sailors will either be saved by the grace of God or condemned to death and eternal damnation. I think there’s an outside chance that Ishmael will be in the former category and the mysterious Ahab will be in the latter. I may be making links which the author didn’t intend, but these associations lend a mythological and religious weight of significance to the story of which I’m sure Melville would have approved.

However, Moby Dick isn’t all gravitas and religious metaphors; for me, Melville saves himself by touches of surprising humour, many of which come from Queequeg, the tattooed heathen from distant lands whom Ishmael befriends. He was another surprise (see how little I knew about this book?) but a welcome one. The unlikely scenes of Queequeg and Ishmael sitting in bed together in their fur jackets and sharing puffs of his peace pipe are bizarre, but they made me warm to Ishmael in a way that none of his moralising and philosophising has done so far. It’s good to have a more human element in among all of the lofty thinking, and Queequeg (or Quohog or Hedgehog as Captain Peleg mistakenly calls him) provides that. I look forward to seeing what Melville does with him as the story develops.

Once I’ve started a book, I don’t abandon it, so Moby Dick would have been finished even if I hadn’t found the first quarter intriguing. However, Moby Dick isn’t a book which has ever particularly called to me before, so even if I wouldn’t have given up on it, it would have remained unread on my shelves for much longer if it weren’t for The Blue Bookcase’s read along, so thanks very much for the encouragement!

Moby Dick by Herman Melville. Published by The Readers’ Digest Association, 1996, pp. 495. Originally published in 1851.

Review: ‘Anderby Wold’ by Winifred Holtby

When I was sent a copy of the beautiful new edition of South Riding by Virago at the beginning of 2011 and was introduced to the writing of Winifred Holtby, it didn’t take me long to fall in love. I was fascinated by the dextrous way she handled such a large cast of characters, making all their stories personal and believeable. She created a community of people by which I was completely absorbed. As I said at the time, I wanted to live there. Later on in the year, I was given the opportunity to discuss the book at one of the Virago Book Club events, something I surprised myself by enjoying even more than their book events with authors. At the end of a lovely evening, during which we reminisced about South Riding and shared our favourite bits, it was made even better when we were each given a copy of one of the newly republished editions of one of Holtby’s novels. My copy of Anderby Wold didn’t even make it home before I dived into it head-first.

When I was sent a copy of the beautiful new edition of South Riding by Virago at the beginning of 2011 and was introduced to the writing of Winifred Holtby, it didn’t take me long to fall in love. I was fascinated by the dextrous way she handled such a large cast of characters, making all their stories personal and believeable. She created a community of people by which I was completely absorbed. As I said at the time, I wanted to live there. Later on in the year, I was given the opportunity to discuss the book at one of the Virago Book Club events, something I surprised myself by enjoying even more than their book events with authors. At the end of a lovely evening, during which we reminisced about South Riding and shared our favourite bits, it was made even better when we were each given a copy of one of the newly republished editions of one of Holtby’s novels. My copy of Anderby Wold didn’t even make it home before I dived into it head-first.

Like South Riding, Anderby Wold is set in Yorkshire and deals with a community struggling with social change. Mary Robson is a young woman who has married her cousin in order to have the means to pay off the mortgage on her family farm and the skills to keep it running. Life in Anderby Wold is hard but quiet until David Rossitur, a young handsome social reformer, arrives and begins to shake things up, not least on Mary Robson’s farm.

Anderby Wold is nowhere near as polished and accomplished as South Riding but it is by no means a bad novel; Winifrd Holtby not at her best is still Winifred Holtby after all. Its focus is narrower, on a few key players rather than each individual in a community, but many of the themes which will be developed and expanded in her later work are present in their nuculaic form here. There is the same emphasis on the indivdual as part of the community and the differences between individual responsibility and social responsibility. It’sreally very difficult not to make this sound incredibly dull, but in fact it paints a fascinating picture of a community going through a time of quiet but important change.

One of the things that has impressed me about both Holtby novels that I’ve read so far is her ability to create characters who are neither inherently good nor inherently bad. Everyone has an opinion that they think is right and good: giving to the poor, workers’ rights and social equality. It’s difficult to disagree with any of them individually, but each character’s approach towards achieving what is right is somehow at odds with that of the others and therein lies the conflict. People do bad things, but noone is bad. There is no villain to boo; instead there is a complicated moral maze which Holtby refuses to guide the reader through. Instead she happily abandons you there, leaving you to find your own way out, and that for me was the main appeal of Anderby Wold.

Anderby Wold by Winifred Holtby. Published by Virago, 2011, pp. 278. Originally published in 1923.

A Classics Challenge – January Prompt

If blogging has taught me one thing it’s that I don’t respond well to book lists. I love creating lists of books that I’ve read, arranging them according to theme or author nationality or date, but if I try to read from a list of set books I know I’m doomed to failure. This (and general disorganisation) meant that I didn’t get round to signing up for Katherine’s Classics Challenge at November’s Autumn, but the prompts are so interesting that I hope it will be alright for me to join in with whichever classic I happen to be reading on the fourth of each month even though I haven’t made an initial list.

If blogging has taught me one thing it’s that I don’t respond well to book lists. I love creating lists of books that I’ve read, arranging them according to theme or author nationality or date, but if I try to read from a list of set books I know I’m doomed to failure. This (and general disorganisation) meant that I didn’t get round to signing up for Katherine’s Classics Challenge at November’s Autumn, but the prompts are so interesting that I hope it will be alright for me to join in with whichever classic I happen to be reading on the fourth of each month even though I haven’t made an initial list.

This month’s prompt asks about the author of the classic that you’re reading at the moment. Because of the various readalongs in which I’m participating at the moment, I actually have three other classics on the go, Middlemarch, Les Miserables and Moby Dick, in addition to the one that I’m going to focus on today. I’ve chosen this book because the author is much less well-known, at least on this side of the pond, and finding out more about her might help me to understand her work a bit more.

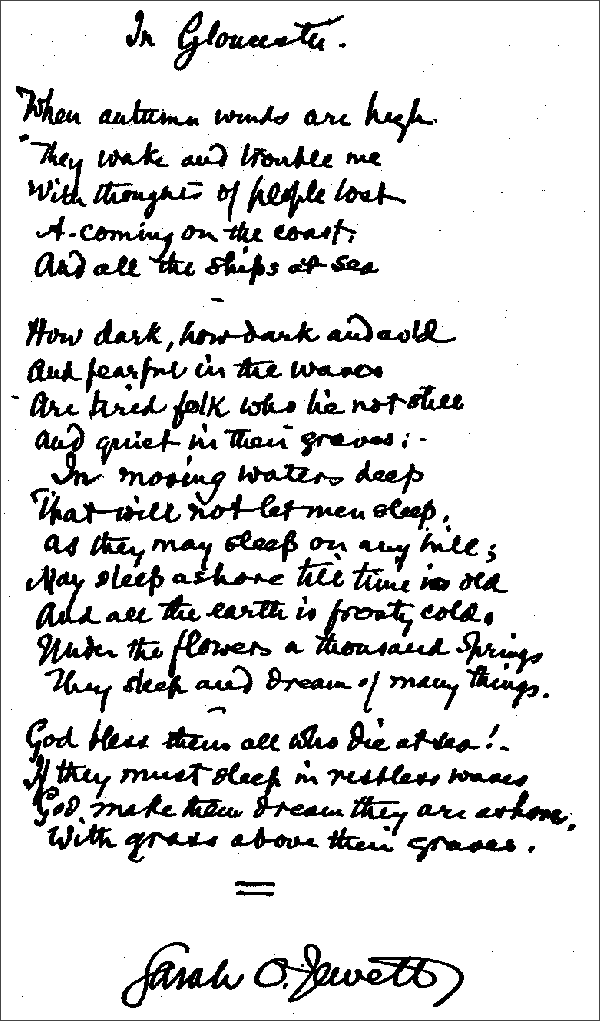

The book that I’m reading right now is The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett.

Sarah Orne Jewett was born in South Berwick, Maine on 3rd September 1849. She died in the same town aged 59 on 24th June 1909.

As a child, she developed arthritis and so was often sent for long country walks to try to ease the symptoms. She also frequently accompanied her father, a country doctor, on his visits to his patients and it is probably from this background that she developed her keen interest in rural domestic life on the Eastern Seaboard. She was educated at the local school, but expanded her knowledge through her family’s library and correspondence with other learned figures.

Sarah Orne Jewett never married. She did have a deep and long lasting friendship with Anne Fields, the wife of the editor of Atlantic Monthly. After his death, Sarah and Anne lived together, giving rise to the speculation that she may have been a lesbian, but it is equally plausible that the two were merely friends and companions.

Jewett had her first short story published when she was 19 in the Atlantic Monthly magazine. She didn’t write novels, preferring sketches, short stories and poems, and was at times quite apologetic about her own writing:

Jewett had her first short story published when she was 19 in the Atlantic Monthly magazine. She didn’t write novels, preferring sketches, short stories and poems, and was at times quite apologetic about her own writing:

It seems to me I can furnish the theatre, and show you the actors, and the scenery, and the audience, but there never is any play!. . . I seem to get very bewildered when I try to make these come in for secondary parts. . .I am certain I could not write one of the usual magazine stories. If the editors will take the sketchy kind and people like to read them, is not it as well to do that and do it successfully as to make hopeless efforts to achieve something in another line which runs much higher?

Her writing was often dismissed as the chatterings of an old maid, because they aren’t driven by plot, and for a long time it wasn’t considered to be worthy of criticism. However, Willa Cather considered The Country of the Pointed Firs to be one of three American works (along with Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter and Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn) to be most likely to achieve permanent remembrance.

Jewett’s writing career was brought to an abrupt and untimely end when she and her sister were involved in a carriage accident when their horse stumbled on a loose rock. Both sisters were thrown from the carriage and, though Jewett’s sister was largely unharmed, Jewett herself suffered from concussion and spinal damage. Afterwards, she experienced frequent dizzy spells, memory loss, pain and lack of ability to concentrate which lasted until her death seven years later.

Jewett clearly wrote about the life she knew and held dear to her heart. Her depictions of Dunnet Landing, the fictional Maine town that provides the setting for The Country of the Pointed Firs, is full of local colour, affection and understanding. It reads almost more like a memoir than a work of fiction, which seems testament to how well Jewett has captured a time and a place and the people who inhabit that in her writing.

2012 Reading Resolutions

Now that I’ve officially brought 2011 to a close on Old English Rose Reads, it’s time to look forward to 2012 and all the delightful reading which can take place this year. It seems only appropriate to make a few reading a blogging resolutions at this time of year, although (in the words of Pirates of the Caribbean) they’re more like guidelines. I feel no qualms about breaking or ignoring them if I change my mind later on (witness my 2011 resolutions, of which I stuck to just one), but I feel it’s nice to have some vague sense of direction when starting the year.

1. I will finally get up to date with all my reviews and I will stay there! As I don’t plan on getting married or moving house this year this should be doable, although I do have a backlog of 73 reviews to get through before I even start on 2012!

2. Comment more. Where I’ve been so busy, I’ve been dashing through everyone’s lovely blog posts on my feed reader and I rarely manage to stop and leave a comment. I really do enjoy the bookish chat that goes on in the comments of blog posts, so I’m going to make an effort to join in a bit more this year.

3. End the year book-neutral. Although the Old English Thorn and I may have a shiny new flat, I appreciate that its primary purpose is as a dwelling place and not a book storage unit (although this is undoubtedly its secondary purpose). Consequently, I’m going to attempt to limit myself to only buying as many books as I read. Ideally I’d like to read more books than I acquire, but knowing how well I respond to limits on my book purchasing I think I’m best to aim a bit lower and see how it goes.

4. Join in with some readalongs. I have a lot of intimidating-looking books sat on my shelves waiting for my attention, and reading them with other people seems the best way to attack them. I’m going to try it with three books this year.

I joined Team Middlemarch with dovegreyreader on 1st December 2011. The plan is to read what is widely considered to be George Eliot’s greatest novel following its original publication schedule:

Miss Brooke – 1st December 1871

Old and Young – 1st February 1872

Waiting for Death – 1st April 1872

Three Love Problems – 1st June 1872

The Dead Hand – 1st August 1872

The Widow and the Wife – 1st October 1872

Two Temptations – 1st November 1872

Sunset and Sunrise – 1st December 1872

Miss Brooke – 1st December 1871

Old and Young – 1st February 1872

Waiting for Death – 1st April 1872

Three Love Problems – 1st June 1872

The Dead Hand – 1st August 1872

The Widow and the Wife – 1st October 1872

Two Temptations – 1st November 1872

Sunset and Sunrise – 1st December 1872

I’ll be posting about each installment when I begin the next one, so look out for a post on Miss Brooke on 1st February.

I’m also joining in with Kate’s readalong of Les Miserables which runs throughout the year. I adore the musical and I bought myself a lovely hardback copy of the Julie Rose translation from a discount bookshop by the British Library but it’s huge and appears to be printed on Bible paper, making it even longer than it appears. Kate’s wonderful schedule makes it seem so manageable, breaking the huge tome down into bitesize morsels, so I’m hoping to be able to stick to it and discover this story as it was originally written. I may even reward myself with a trip to the theatre to see the musical again after I’ve finished. Once again, the plan is to post at the end of each section.

I’m also joining in with Kate’s readalong of Les Miserables which runs throughout the year. I adore the musical and I bought myself a lovely hardback copy of the Julie Rose translation from a discount bookshop by the British Library but it’s huge and appears to be printed on Bible paper, making it even longer than it appears. Kate’s wonderful schedule makes it seem so manageable, breaking the huge tome down into bitesize morsels, so I’m hoping to be able to stick to it and discover this story as it was originally written. I may even reward myself with a trip to the theatre to see the musical again after I’ve finished. Once again, the plan is to post at the end of each section.

I’ve also joined the much shorter January readalong of Moby Dick hosted at The Blue Bookcase. As I studied a literature course at university which focused exclusively on English literature it’s not a book I ever studied, but it’s one I’m curious about (helped by the recent and fortuitous purchase of a lovely edition of the book shortly before the readalong was announced). I’ll be posting according to the schedule on the Blue Bookcase.

Jan 12: Chapters 1-28

Jan 19: Chapters 29-55

Jan 26: Chapters 56-93

Feb 2: Chapter 94-epilogue

Jan 12: Chapters 1-28

Jan 19: Chapters 29-55

Jan 26: Chapters 56-93

Feb 2: Chapter 94-epilogue

So, there are my plans for 2012. Above all, my plan is to continue to enjoy my reading and to discover many more favourite books.

2011 Wrap Up

The new year got off to an inauspicious start yesterday, when the Old English Thorn and I found ourselves unexpectedly on a coach from Edinburgh to Heathrow after gale force winds meant that the aeroplane we were supposed to be on was unable to take off. What should have been a one hour twenty minute flight turned into an eight and a half hour coach journey, followed by the tube across London and then a train back out again. Door to door we were travelling for a little over fourteen hours.

Thankfully, I have the day off today to recover, providing me with the ideal opportunity to reflect on the year gone by before launching myself into the new one tomorrow.

In 2011, I met (exactly!) my goal of reading 150 books totalling 40,659 pages. I slowed down an awful lot after getting married and halving my commute time, so I’m pleased I still managed to get to 150. The full list with links to my reviews can be found here.

I discovered some fantastic new authors, including E. F. Benson, Winifred Holtby, D. E. Stevenson, Margery Sharp and Michel Faber who I know I’m going to enjoy reading more of in 2012. There were so many of them, not to mention old authors that I revisited, that it has been difficult to select the top ten books that I read in 2011, but these would be the ones that I would most heartily recommend. In the interests of fairness, I haven’t included rereads, or two of these spots would be occupied by the ever wonderful Miss Austen.

South Riding by Winifred Holtby (1936)

South Riding by Winifred Holtby (1936)

I read this book quite early on in the year, but it’s stuck in my mind ever since. I was instantly drawn into the world of the fictional Yorkshire constituency and its inhabitants, utterly entranced by its impressive combination of detail and breadth. Winifred Holtby introduces such a range of characters from all walks of life, but they are each described so well, however briefly, that I felt I knew each and every one of them. It’s a rare talent for an author to be able to make me care so deeply about so many characters but Holtby manages it with consummate skill. I was reluctant to finish the book and I’m treasuring up the rest of Holtby’s work to read when I need to treat myself. Review

Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell (1851)

Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell (1851)

Although Cranford is less than half the size of South Riding, it is in many ways a similar type of book, focusing as it does on the mundane issues of a small community and yet somehow making them utterly fascinating. With each episode I found myself becoming more and more involved in town life as though the book were gossip being related directly to me. As with South Riding, I wanted to move to Cranford and live there with its community of brave, humorous, kind and gentle ladies. It made me smile even when it made me cry. It’s a delightful little read, surprisingly touching and highly recommended.

The Foolish Gentlewoman by Margery Sharp (1948)

The Foolish Gentlewoman by Margery Sharp (1948)

Margery Sharp was one of my discoveries this year. She writes the sort of humorous, gentle novels which seem to fit into the Persephone canon perfectly. While this particular novel displayed the same wit, charm and light touch that I expected, it was nowhere near as breezy and flippant as The Nutmeg Tree which was my introduction to the author. It had a wistfulness and sadness about it which I thought actually made it even better. The humour was set off by the seriousness and I liked the way that everything couldn’t be wrapped up perfectly and sorted out in a fairy tale ending. I was impressed that Sharp was brave enough to do that, and it’s made me look forward even more to discovering the rest of her work.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver (1998)

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver (1998)

This remarkable book got 2011 off to a fantastic start for me. The story of a misguided missionary who moves his family to Africa during the 1950′s but utterly fails to connect with the locals on any level was something of a departure from my usual reading fare, but I was completely drawn in by the narrative style. The voices of the four daughters and their mother as they tell the story of their struggles are engaging both intellectually and emotionally, weaving a rich tapestry of opinions, viewpoints and voices. My heart ached for each and every one of them as they tried their best to survive and to integrate in spite of the preacher’s inability to understand either the natives or his family. Exceptionally written. Review

The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber (2002)

The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber (2002)

If it weren’t for the rather risque subject matter of this book about a prostitute’s attempts to make her way in the world, it would almost be possible to believe that it were actually a Victorian novel rather than a novel about the Victorians. The writing is elegant and mesmerising; it even made me appreciate the advantages of present tense narration and books which address the reader directly, both of which I usually dislike intensely. Faber writes brilliant, diverse female characters and Sugar, Agnes, Sophie and Mrs Fox are some of the best that I’ve encountered this year. I’m not convinced about the rest of Faber’s work as it looks to be mostly modern in its setting, but I have two of his other books sitting on the shelf and 2012 is the year to give them a try. Review

Before They Are Hanged by Joe Abercrombie (2007)

Before They Are Hanged by Joe Abercrombie (2007)

This is the second book in a trilogy, so it feels rather odd to have this one on my top ten list and not the first one. Often the middle book can fall into the trap of being mediocre filler between the interesting exposition in book one and exciting denouement in book three. Not so in this trilogy. I liked the first book well enough, but in Before They Are Hanged the trilogy really comes into its own. Start with The Blade Itself and discover an exciting, bloody fantasy novel. I can’t wait to finish the series. It’s also reminded me that I used to read a lot more fantasy than I have done recently. I must rectify this if it’s all going to be this good.

Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson (1997)

Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson (1997)

If a book were ever to be written specifically for me, it would be an awful lot like Human Croquet. This book was bizarre, but very definitely my kind of bizarre. It had all the elements that I love in a book: word play, humour, clever time shifts and twisted fairy tale tropes. I doubt it will appeal to everyone because of its odd structure and peculiar style, but it’s definitely worth a try because there’s every possibility that you’ll love it as much as I did. Read it and discover that Atkinson writes more than just the detective fiction for which she seems to be best known. Review

The Wedding by Dorothy West (1995)

The Wedding by Dorothy West (1995)

The Wedding is possibly the most thorough and insightful explorations of racism in America that I’ve read since I first encountered Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor when I was twelve. It surprised me by how different it was to what I had expected. There were no lynchings, violence or hate crimes, just assumptions, opinions and social conventions which are insidious and pervasive. In many ways it’s like reading an Austen novel, but here people are discriminated against ever so politely based on the shade of their skin rather than their class. It also shows how complicated the issue is, with people who consider themselves coloured but have pale skin being looked down on by some as not black enough and by others as all too black and indeed vice versa. It’s a very interesting and thoughtful book.

Wild Swans by Jung Chang (1991)

Wild Swans by Jung Chang (1991)

I’m a little bit surprised that this is the only non-fiction book to make it onto my 2011 list, as I’ve read a few excellent memoirs this year. However, Jung Chang’s story of her grandmother, her mother and herself growing up over a period of huge change in China wins in scope, in detail and in the sheer remarkable nature of the story being told. Through Chang and her family, we see China change from a land of imperial warlords and their concubines to one in the iron grip of Mao’s dictatorship. It provided a compelling insight into a world that is completely alien to me and I found it utterly fascinating. Review

The Uxbridge English Dictionary by Jon Nasmith et al (2005)

The Uxbridge English Dictionary by Jon Nasmith et al (2005)

Ever since I was first introduced to it by my parents while listening to the radio on a long car journey, I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue has been one of my favourite comedy shows. I enjoy every round, however silly, but I particularly love listening to the ludicrous yet ever so clever new definitions for words that the teams come up with in the round called Uxbridge English Dictionary. This book is a compendium of the best of those definitions and it had me crying with laughter on every page. If you like the radio show, you’ll love this book. If you’ve never heard it, I insist you go forth and do so immediately, but anyone with an appreciation for the peculiarities of language should enjoy this regardless.

So, 2011 was a really good reading year for me. I’ll be looking at tmy plans for 2012 tomorrow. I’m excited already!

2011 Victorian Literature Challenge Wrap Up

Back in December 2010, I signed up for my first reading challenge on this blog: the Victorian Literature Challenge hosted by Bethany at Subtle Melodrama. I still don’t think I’ve quite grasped the mechanics to participating and linking posts, but I really enjoyed the books that this challenge prompted me to read.

Back in December 2010, I signed up for my first reading challenge on this blog: the Victorian Literature Challenge hosted by Bethany at Subtle Melodrama. I still don’t think I’ve quite grasped the mechanics to participating and linking posts, but I really enjoyed the books that this challenge prompted me to read.

The challenge had four different levels of participation:

Sense and Sensibility: 1-4 books.

Great Expectations: 5-9 books.

Hard Times: 10-14 books.

Desperate Remedies: 15+ books

I said in my initial post that I was aiming for the Hard Times level, with the intention of reading one book each month. In fact, I’ve managed to achieve the dizzy heights of Desperate Remedies, reading a grand total of sixteen Victorian books, including short stories, novels and poetry.

Because of my increasingly enormous review backlog, many of these books are ones that I haven’t written about here yet (although I fully intend to eventually). To give an idea of what I thought about the books I read, the list below is ranked in order of preference and includes the star rating that I gave each book on LibraryThing (5 = I loved it; 4 = I really liked it; 3 = I liked it; 2 = It was ok; 1 = I didn’t like it). All the links are to my reviews, where they exist.

- Cranford by Elizabeth Gaskell (5)

- The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot (4.5)

- Cautionary Tales by Hilaire Belloc (4.5)

- The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (4.5)

- Lady Audley’s Secret by Mary Elizabeth Braddon (4)

- Elizabeth and her German Garden by Elizabeth von Arnim (4)

- The Prisoner of Zenda by Anthony Hope (4)

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (4)

- More English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs (4)

- The Warden by Anthony Trollope (3.5)

- The Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith (3)

- Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens (3)

- Wessex Tales by Thomas Hardy (3)

- The Monk and the Hangman’s Daughter by Ambrose Bierce (3)

- The Professor by Charlotte Bronte (2.5)

- Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (2)

As you can see, I really enjoyed most of these books, and all of them proved an interesting reading experience even if I didn’t like them as much. All of the books that I read were by different authors, which was one of my aims when I set out, and as a result I ended up discovering lots of new-to-me Victorian authors which I might not have done without this challenge. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Elizabeth von Arnim, Anthony Hope, Joseph Jacobs, Anthony Trollope and Geroge and Weedon Grossmith were all authors I hadn’t read before, but I already have second books by all of them (except George and Weedon Grossmith who apparently only wrote The Diary of a Nobody).

In addition to discovering some new favourites, I also had fun encountering some familiar faces. I made it through a Thomas Hardy book for the first time ever! While The Wessex Tales did nothing to alter my opinion that Hardy is all doom and gloom, it did prove to me that I can get through it and even enjoy it (albeit in small doses). I think it will still be a while before I attempt Jude the Obscure, but I might perhaps be tempted to try Far from the Madding Crowd in 2012.

Reading Nicholas Nickleby was exactly the experience that I had expected, filled with deserving poor, miserly uncles and charitable rich men. I was disappointed because of the lack of decent female characters and the overall predictability, but I’ve come to the conclusion that I should stop hoping that Dickens will do anything other than what I know he’s going to do and appreciate him for what he does, if that makes any sense at all. There’s a new BBC adaptation of Great Expectations coming this Christmas, so I may reread that book as I know Miss Havisham bucks the trend of insipid women quite spectacularly. Now that I’ve reminded myself that Dickens does exist outside of the classroom, I’m also going to devote a bit more of my reading time to him next year in honour of the Dickens Centenary.

My favourite book by far was Cranford which I had read in part before the challenge. I started reading it shortly after watching the BBC adaptation, but I must have misplaced the book when I moved back home after university and somehow never picked it up again until now. I’m glad I did, because I fell in love instantly with its cast of brave, kind ladies. It’s easily one of my favourite books from 2011.

Although not my favourite book from this challenge by a long way, perhaps the most interesting to read from a critical point of view was The Professor by Charlotte Bronte. I consider Jane Eyre to be one of my favourite books of all time and I really wanted Charlotte Bronte to be like Jane Austen, whose books I find all equally fantastic. However, I was surprised by how indifferent I was towards this particular book. It wasn’t bad (this is, after all, Charlotte Bronte) but it didn’t capture my heart or my mind and I can see why it was only published after the successes of her other novels.

So, all in all, a really good challenge. I’m glad that I participated and thank you once again to Bethany for hosting!

Why I don’t use the library

As someone who reads quite a lot, people often ask why I don’t use the the library more. Before I was married, my answer was that my commute was so long each day that I got home too late to use it in the evenings, and my weekends were taken up with visiting the Old English Thorn and engaging in wedding related activities. Now that we’re living together a sensible distance from our workplaces I no longer have this excuse and not so long ago, I posted enthusiastically about my new found ability to use the library.

As someone who reads quite a lot, people often ask why I don’t use the the library more. Before I was married, my answer was that my commute was so long each day that I got home too late to use it in the evenings, and my weekends were taken up with visiting the Old English Thorn and engaging in wedding related activities. Now that we’re living together a sensible distance from our workplaces I no longer have this excuse and not so long ago, I posted enthusiastically about my new found ability to use the library.

Libraries are undeniably wonderful places which do the world of good and make books and reading accessible to everyone. I have fond memories of visiting the library as a child, browsing the shelves for as long as I was allowed and coming back in the car with my nose already firmly buried in one of my new acquisitions. It was a magical place then, shelves filled with opportunities, and it’s still excellent if all I want to do is potter happily around and pick up books from the shelves as they take my fancy. I’ll continue to use it on occasions when I wish to do that, but on the whole, I don’t use the library any more.

The two main reasons people usually state that they don’t use the library are:

- They like to own books, not just read them

- It’s more convenient to buy a book than use the library

Both of these are true for me. Few things give me greater pleasure than sitting on our sofa, looking across the living room at our wonderfully stuffed shelves and it is indeed a bit of a pain to have to reserve a book on the library’s website, wait for the email saying that it has arrived, load up my carrier bags with books to take back and traipse along to the library, rather than just pointing and clicking on Amazon and letting them take care of the rest.

However, the main reason that I choose not to use the library will probably surprise a lot of you: it saves me money.

Yes, you did read that correctly. I have saved money this year by not using the library.

To buy and own the books that I have read so far this year, which, by and large, is what I have done, cost me £240.26. It may sound like quite a lot, but as I’ve read 143 books, that works out at £1.68 a book which is a long way from extravagance. While a few of them were gifts or review copies which cost me nothing, the vast majority were bought myself. They range from £0.20 charity shop purchases to brand new Folio Society volumes which are costly but irresistible in their beauty. These books are all mine to do with as I please now. I can put them on my shelves to read again when the mood takes me; I can give them away to other people as gifts; I can sell them on Amazon or at a car boot sale; I can put them on BookMooch or take them to the Notting Hill Book Exchange and swap them for other books; I can donate them to charity. If I wanted to, I could use them to start a rather substantial fire if our heating ever fails (not that I would ever consider doing something so terrible). The point is, I paid that money and I own those books. They are mine.

To borrow the same books from the library would have cost me £255.40, which is £1.79 a book and £15 more than I actually paid. This is not taking into account the inevitable fines when someone reserves a book that I’ve borrowed so I can’t renew it and can’t return it until the following weekend because I work during the only weekday hours that the library is open. Had I taken these books out of the library, I would have spent more money and yes, I would have had the same hours of reading pleasure, but I would have nothing tangible to show where my £255 had gone.

If I wanted to reserve books that are marked down on the website as being in my local library just to make sure they were there and waiting for me when I managed to visit the library, this lot would have cost a further £23.40. My county library charges £0.60 to reserve a book from their stock, so even if I don’t feel the need to reserve books in my branch, any book that I want to read that isn’t in the local branch costs me £0.60 automatically to request. If a book isn’t held within the county, it’s a further £4.40 charge to source it from elsewhere, meaning any book borrowed through inter-library loan costs an impressive £5. If I’m going to spend £5 on a book, I’m going to spend my money somewhere which doesn’t expect me to give said book back in three weeks’ time! It’s going to be mine to have and to hold till death do us part. I appreciate that there are administration and postage costs involved in the inter-library loan process, but if I can buy the book for much less than this, why would I pay the extra? Who would?

As a rule of thumb, anything that’s out of print is cheaper to buy than to borrow. One of my favourite books that I read this year is Margery Sharp’s The Foolish Gentlewoman which I sought out after adoring The Nutmeg Tree last year. To borrow it from the library would have cost £5. I bought my copy in a second hand book shop for £2, and even those without access to the bounty of Charing Cross Road can buy their very own copy for £2.81 including postage and packaging from Amazon Marketplace. On the one hand, it makes me sad that libraries don’t have the funds or the space to hang onto books like this and keep them out on the shelves, as it means that fewer people will find them and fall in love with them by chance. On the other, more objective hand, I understand that it makes little sense to keep something in circulation when it is no longer popular.

Libraries have to be selective. They are designed to cater to the entire population and so their stock tends to reflect what is current and what is popular. This is not a bad thing. It is in fact a very good thing that libraries are well stocked with the latest bestsellers and perennial favourites. I think it’s great that anyone with a library card can walk in and take home one of these books for free. It just doesn’t reflect how I choose to read. If you look at my reading list, you can see that very little of it is recent writing; only four books were published this year. Consequently, I don’t really benefit from the constantly updated display of new releases which stands by the entrance to the library. I’ve also not read that many classics this year; I’ve read old books, but most aren’t prominent enough to have multiple copies sat on the shelves in the library. Many of the books I’ve read are ones that have fallen into obscurity for one reason or another. Old children’s books which are no longer fashionable; lesser known works of well-known authors; early twentieth century women’s novels; names that I’ve stumbled across mentioned elsewhere and then gone in search of without knowing anything about them. It may sound sad, but for me and the way I read, the library cannot compete with the Internet.

If I didn’t have money to spend on books, I would no doubt have picked out a selection of titles each week from what was available on the library shelves and I would have enjoyed myself doing it. However, as I do have money that I choose to spend on books, I’d rather read the specific titles that I actually want to read than those books in which I have a vague interest. And to do this, it’s cheaper for me to buy them.

Review: ‘Black Butterfly’ by Mark Gatiss

I don’t often stray into the world of mystery stories. In our (reasonably extensive) library, there is only one shelf of mystery novels tucked away in a corner. It’s not that I don’t like them per se, it’s just that there are other genres that I prefer. However, I can occasionally be tempted by a good historical mystery, I love Lindsey Davis’ Falco novels for example, so when I stumbled across Mark Gatiss’ trilogy about the delightful rogue Lucifer Box, each book set in a different era, I was intrigued. I thought the first book was delicious, filled with Oscar Wilde type wit and deviancy. The second book was less my cup of tea as Lucifer Box’s character was much less prominent. Sadly the third and final (I think) book, Black Butterfly, continued the downwards trend and was my least favourite so far.

I don’t often stray into the world of mystery stories. In our (reasonably extensive) library, there is only one shelf of mystery novels tucked away in a corner. It’s not that I don’t like them per se, it’s just that there are other genres that I prefer. However, I can occasionally be tempted by a good historical mystery, I love Lindsey Davis’ Falco novels for example, so when I stumbled across Mark Gatiss’ trilogy about the delightful rogue Lucifer Box, each book set in a different era, I was intrigued. I thought the first book was delicious, filled with Oscar Wilde type wit and deviancy. The second book was less my cup of tea as Lucifer Box’s character was much less prominent. Sadly the third and final (I think) book, Black Butterfly, continued the downwards trend and was my least favourite so far.

In The Black Butterfly, Queen Elizabeth II has just come to the throne and Lucifer Box is being shoved off his as he has retirement foisted upon him. In spite of this, he finds himself compelled to investigate when perfectly sensible public figures start dying in reckless accidents. Who is the mysterious Kingdom Kum? And who or what is the Black Butterfly? But someone does not want him to find out.

As each book in this trilogy is set in a different era, Lucifer Box naturally ages as the books progress. I love the idea of the aging spy, and seeing how he adapts and changes with time. However, in practice I didn’t really think it worked. Although Lucifer complains about his reduced capacity for action, there seemed to be no material difference between his abilities in this book and the earlier ones. The only difference is that he’s more curmudgeonly about it all. The sharp wit that I loved so much in the first book was sadly lacklustre in The Black Butterfly.

The plot was as amusingly ridiculous as I have come to expect from a Lucifer Box story. In particular, I thought that the link to the Boy Scouts was wonderful and really humorous. However, the primary attraction of this series to me is the central character and I found him diminished in this novel, so consequently my enjoyment was also diminished. At just over 200 pages long, I don’t feel the time spent reading it was time wasted as it was mildly entertaining. However, it’s definitely my least favourite of the series and I’m quite glad it’s come to an end.

Black Butterfly by Mark Gatiss. Published by Pocket Books, 2009, pp. 204. Originally published in 2008.